By Art Jahnke

Photos by Vernon Doucette

Employed in the twelfth century to spread the word of God, Ajami was used in the twentieth century to preach resistance to occupying European powers.

Employed in the twelfth century to spread the word of God, Ajami was used in the twentieth century to preach resistance to occupying European powers.

To determine the literacy rate of the Hausa people in the west-central African country of Niger, census takers trek from village to village counting the people who read and write the country’s official language: French. In Senegal, they visit the schools of the Wolof people, tallying all who can read French. And in Guinea, the Fula people, whose native tongue is Pular, are questioned about their proficiency in — French.

The findings of the census workers invariably discourage Western-trained educators in Africa’s urban centers. In 2005, UNESCO put the literacy rate in Niger at 18.7 percent. In Senegal, it was 42.1 percent. And in Guinea, it was 41.1 percent. But curiously, in the rural villages of Niger and Senegal and Guinea, the people are untroubled by the UNESCO numbers; they know that almost all villagers are pretty good readers, albeit of a language that happens not to be French. Instead, the people use a centuries-old writing system that applies modified Arabic script to a phonetic rendering of their language, be it Hausa, Wolof, Pular, Swahili, Amharic, Tigrigna, or Berber. The language is called Ajami, and it is used in written communication in many countries across a swath of Islam-influenced sub-Saharan Africa.

Virtually unknown to most Westerners, Ajami has a rich history: it was created centuries ago by Islamic teachers to disseminate the religion to the African masses, and it became, in the twentieth century, the chosen language of anticolonial nationalist resistance. Today, says Senegal native Fallou Ngom, who came to Boston University last fall as a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of anthropology and director of the African Language Program, it’s a key that can unlock the African perspective on centuries of history, as well as literature, religion, and even medicine.

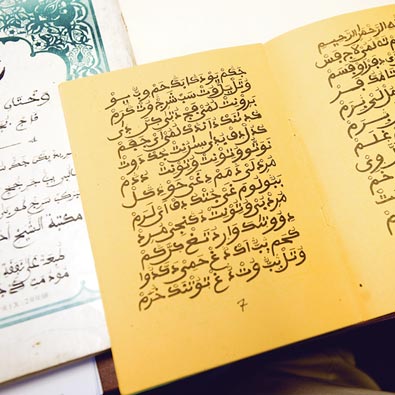

“This is a form of writing whose documents are as varied as all knowledge,” says Ngom. “There are poems that deal with religion and try to teach us how to be a good person. And there are poems that are more secular, like thoughts about a beautiful woman. You have historical documents that describe things that happened a long time ago, and you have tales and stories and even texts on pharmacopoeia — what to do if you are bitten by a snake or how to heal children with a speech disorder, stomachache, or rheumatism. The amazing thing is, we don’t even know what’s in most of these texts, because they have never been translated.”

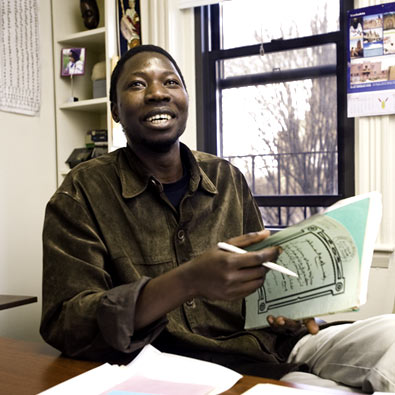

Fallou Ngom, director of the African Language Program, hopes to build an Ajami center at BU to teach the complex writing system to anthropologists, historians, and other researchers.

Fallou Ngom, director of the African Language Program, hopes to build an Ajami center at BU to teach the complex writing system to anthropologists, historians, and other researchers.

Translating Ajami texts, and more important, equipping the next generation of scholars with the skills to translate the texts, are two goals Ngom has set for the African Language Program at BU, which is the first language program in the country to incorporate Ajami in a language curriculum.

James McCann, a CAS professor of history and the director of BU’s African Studies Center, read Ngom’s work on Ajami scripts and urged him to come to BU from Western Washington University, where he was an associate professor in the department of modern and classical languages.

“Ajami is an important key to understanding the daily transactions of a culture,” says McCann. “It’s in Ajami that you read things that say, ‘I lend you this money for this horse.’ Those are the transactions that help us understand the inner workings of a society.”

Ajami texts include a wide range of sociological, historical, and cultural information that wasn’t captured by the elite writers of Arabic, McCann adds. Take the history of Timbuktu. Everything that’s known about the Malian city is written in Arabic, but in 2000, more than 500 pages of Tamashek Ajami documents dating from the tenth to the sixteenth century were found in a private library in the area.

The discovery of the hidden history of Timbuktu and other Muslim cities in Africa is a frustrating subject for African scholars like Ngom. Today, nine years later, only a handful of those documents have been translated. “You see the problem?” Ngom asks.

There are, it seems, both good and bad reasons for the dearth of Ajami readers. Practically speaking, Ajami is a difficult writing system to learn. A reader must know, at a minimum, both the Arabic script and the spoken language of a particular African culture. And to really understand what is written, says Ngom, one should have a good understanding of the culture. But the main reason so few non-Africans read Ajami, or have even heard of it, is that the two cultures that dominated sub-Saharan Africa — Arabs and Europeans — were convinced that whatever African wisdom was preserved in the hybrid writing system could not possibly have any value.

From the perspective of Islamic conquerors, says Ngom, Ajami was a tool to spread the word, but it was a tool that served the subliterate masses. “And when the Europeans arrived,” he says, “recognizing the existence of an African intellectual history was tantamount to purposefully undermining the agenda of the colonial administration. The African had to be portrayed as intellectually challenged, with a history that began with the arrival of Europeans.”

“People have a general impression of Africa as a continent with an oral history, but an illiterate continent,” says Jeremy Berndt (UNI’98), an expert on Islamic African studies, who holds a Ph.D. in African history from Northwestern University. “In fact, there is a literary tradition that dates back centuries. Pretty much wherever there were Muslims, there was Ajami.”

Berndt describes Ajami scholarship as “a field where a lot needs to be done” and says Ngom’s program expansion would make “an enormous contribution to understanding Africa.”

Ngom’s research, published in the International Journal of the Sociology of Language, the Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Language Variation and Change, and African Studies Review, among other academic journals, argues that Ajami has done more than fix a record of African cultures — it has helped to shape them.

Ajami was put to religious use as early as the twelfth century, Ngom says, when Muslims made their way to sub-Saharan Africa and urged native peoples to study the Koran. Intended to spread Islam to African people who couldn’t read the religious texts in Arabic, Ajami did that, albeit with a few convenient twists. Ngom says the many versions of Islam that were planted in sub-Saharan countries were altered and Africanized to meld with existing animist religions. Those Africanized types of Islam simply chose to ignore many strictures that were culturally incompatible, such as those that require women to hide their faces and those that forbid physical contact between unmarried men and women.

“They interpreted the Koran in a way that would fit their social context,” he says. “Things like wearing a veil were not even part of the discussion.”

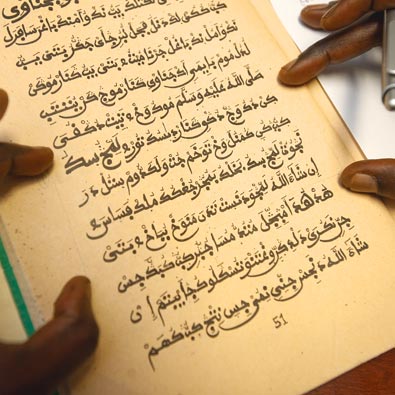

The writing below is excerpted from “Reward to the Grateful: On the Way to the Ocean,” a poem by Serigne Moussa Ka about the deportation by the French of the Sufi leader Bamba (1895-1902). It is one of the many anticolonial poems and stories that have been preserved in Ajami script.

Muusaa, Khaadimul Khadiim,

the one who has surpassed others, said

to you who asks the reasons for the celebration

of the departure of our leader Khadiim (Bamba)

from his home of Mbakke-Baari.

"On the instructions of the Creator,

I left on Saturday the 18th

to fulfill the divine work in the month of Safar."

The story occurred in the year one thousand three hundred

and thirteen (1895), this is the reliable date.

If you listen to me, today I will tell you again,

so that those sleeping, their hearts may be awake again.

If you don’t know, then ask in order to know what you don’t know.

Ask about the story of the one who gave you what no one else has.

Oh blind people, the person with good eyes is here, pay attention.

If you don’t know, you have no excuse but to ask.

If you don’t follow God, then follow your leader of choice,

or when in trouble, don’t complain. I will not go any further!

By the eighteenth century, says Ngom, many Muslim villages in sub-Saharan Africa had a learning center, and the language used to disseminate the teachings of the Koran and other texts was Ajami. By that time, he says, Ajami had become a reliable indicator of a community’s cultural loyalty. Those Islamic communities who perceived their heritage as coming from the Middle East chose to write and read Arabic, while more Afrocentric communities relied on Ajami. Even today, he says, the use of Ajami signals a village whose first allegiance is to a black African culture.

“Without Ajami,” says Ngom, “Africa would be very different; you would probably have a lot more animism and more religions similar to those of Native Americans.”

Naturally, in anticolonial movements of the twentieth century, the tool that was created by jihadists to spread the word of God was put to new purpose: to spread the word of resistance and self-reliance.

“In Senegal,” says Ngom, “Ajami was used to disseminate among the Murids the teachings that the people could make it by themselves, that they didn’t need the French and they didn’t need the Arabs.”

In Fuuta Jalon in the highlands of French-occupied Guinea, for example, an early twentieth-century Ajami poem exhorted readers to:

Ngom argues that Ajami has done more than fix a record of African cultures — it has helped to shape them.

Ngom argues that Ajami has done more than fix a record of African cultures — it has helped to shape them.

Get rid from Fuuta those railways, and those

that work on the roads, ordered by the

evil people deprived of Eternal happiness.

For the red pagans, deemed to hell’s fire

where they will be suffocated through

torture as

the tightening of a belt.

Don’t let the believers be a victim of the

insults inflicted upon them by those

damned

Kafirs that you will burn.

Another poem, written in Ajami at the end of World War II by the popular Fulani writer Cerno Abdourahmane Bah, warns:

None of us was consulted about what we had

to do.

They have been led as animals, exploited to

satisfy every need, going up and down,

without knowing the reason why!

…

Among all nations, so numerous in the world,

we were chosen:

We are the black people, to work hard, and to

supply contributions

That cannot be known.

More than sixty years after that poem was written, Ngom finds himself in a position to help the Western world finally come to know the contributions of the colonized people. In his first year here, he has taught four students how to translate Ajami texts written in two languages: Wolof and Pular. The African Language Program now teaches both the Latin-based script and Ajami script in Wolof, Fuuta Jalon Pular, and Hausa. In the next few years, he says, he dreams of building an Ajami-focused teaching center that would work with anthropologists, historians, literary scholars, and medical experts to unlock the secrets in the Ajami literatures of Africa.

Jennifer Yanco, a lecturer at the African Studies Center and the U.S. director of the West African Research Association, a nonprofit consortium of more than forty universities housed at BU, believes that Ngom’s effort could encourage an important correction of the historical record.

“In the popular mind, Africa is often thought of as largely illiterate,” says Yanco. “But Ajami documents attest to a significant history of literacy there, dating back to well before European colonialism. These are historic documents covering science, philosophy, and diplomacy, among other things, and they document not only colonial history but precolonial history from the point of view of the people who lived it. They are valuable parts of the human heritage.”

Ngom sees a more practical potential benefit.

“In the big picture,” he says, “the knowledge that is captured in Ajami could really help all of us, because it can help the whole world to see things differently.” ■

By Nathaniel Boyle

CAS associate professor Fallou Ngom on what Ajami can teach us.

More Feature Stories | Or Click Here forThis Issue's Table of Contents

Winners

BU's best athletes on what pushes them, scares them, and keeps them at the top of their game

Untrue Stories

A genealogist reveals the painful truth about three Holocaust memoirs: they're fiction

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Comments

On 17 April 2013 at 6:39 PM, Velma Van Ault wrote:

Wow, I would love to learn about this. This orthography sounds interesting and has a lot to offer.

On 5 October 2011 at 7:20 PM, Yahya Bin Jutte wrote:

I want to Learn.

On 26 May 2011 at 1:59 AM , Mosa AL Zowelei2 wrote:

I want study with you english After the English I want cmplet my studying In BU please please please helpe me

On 20 January 2011 at 4:34 AM, amoctad wrote:

Pr NGOM is doing a great work in promoting Ajami worldwide ! His researches show us that colonized people (especially African people) have also a writing culture not only oral traditions.

On 18 September 2010 at 3:19 PM, Tom Glick (CAS) wrote:

Ajami is the African counterpart of "Aljamiado" (Spanish written in Arabic characters; same etymology), as written by Spanish Moriscos in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and which has been very well studied. Start with the Wiki article on Aljamiado.

On 19 August 2010 at 9:37 PM, Mor Gueye wrote:

This is scientifically passionate, interesting and worth studying. I still remember letters my father and some of his friends were writing to each other in Ajami, what we were calling Wolofal in my area. I even have kept one letter a friend of his wrote to him when my elder brother was passing his exam in Arabic school, and needed his birth certificate. I now start realizing the scientific and cultural weight of such an aspect. I wish i could keep a lot more about my father's documents.

On 21 January 2010 at 8:28 AM, M Nnoli (MET) wrote:

What a very interesting and refershing ariticle--and this is only the very very tip of the iceberg! My husband is an Ibo and I am exposed to a very very rich culture. As an African American it is like living in two worlds-just wait until you enter the religious aspects! I am looking forward to reading more updates.

On 12 August 2009 at 2:50 PM, Dalia Armonas (GRS'74) wrote:

What an interesting discovery! For me the most exciting thing is that we can learn much more about the daily life and customs of Africans that lived centuries ago than we know now. I'm glad that BU found Dr. Ngom!

On 12 August 2009 at 1:49 PM, Joshua Haynes (SMG'02) wrote:

As a self-proclaimed linguaphile, I thank you for bringing the topic of West African literary history to the forefront. I feel it is important, however, to highlight some inconsistencies in this article. The author at times confuses the idea of Ajami as a language and Ajami as a script/alphabet. To be clear, Ajami is not a language, but a script using the Arabic alphabet to write West African languages, usually when no indigenous scripts existed. (I'd hesitate to call Amazigh/Berber written in Arabic script Ajami, as Tifinagh is the native script that has been revived in some locations. Also, Amharic and Tigrinya have the Ga'ez script.) One other element from the article that confuses is the historical versus contemporary usage of Ajami mélanged with the ability to read Arabic. I've just spent the last two months working on a literacy via cell phone project in 70 rural Nigerién villages. In the very rare instance where I came across someone who could read the Arabic script - Arabic because he could read the Qur'an, not texts in Hausa or Zarma - it was a phonetic exercise and not an example of functional literacy, which does not agree with the article's opening thesis. (For validation, I speak Arabic and some Hausa and Zarma.) There is no corpus of Hausa or Zarma texts, written in Ajami or Boko (the Hausa-Latin script equivalent) that people can read. There may indeed be pockets where people are learning native languages with the Ajami script, perhaps northern Nigeria, but this does not discount the shocking, yet true, illiteracy rates. Despite these few points, I am thrilled that you've highlighted this rich historical treasure that will allow us to better understand the richness of the West African history and culture!

On 20 July 2009 at 9:01 PM, Allan D. Austin wrote:

I am the author-compiler-editor of African Muslims in Antebellum America: A Sourcebook (1983) and African Muslims in Antebellum America: Transatlantic stories and Spiritual Struggles (1997). I reprint in both 16 manuscripts by sub-Saharan Africans enslaved in the United States. Arabic letters are used but several passages cause trouble to translators. Perhaps many sections are in Ajami. I had not heard anything about it, but I do take hints from some of the people in the books that they wrote their languages using Arabic letters. Perhaps you might take a look at these MSS and pass on your conclusions to me.

On 20 July 2009 at 8:03 AM, Burch Ford (MET'72) wrote:

This article (Lost Language) is fascinating. I loved in Senegal in the Peace Corps for two years ('67-'69) and spoke Wolof fluently,which at the time was not transcribed. I never heard of Ajami, though now wonder if that was the script that looked like Arabic, used in the Koranic schools (Murid and Tidjani) and written on small wooden prayer boards (aloubas), two of which we have hanging on our walls. Thanks for this new information. I look forward to hearing more about it and have written to my friends in Senegal to ask them about Ajami too.

Post Your Comment