A “Rock Star” of the Classics

Donald Carne-Ross made literature exciting to students

| From Obituaries | By Katie Koch

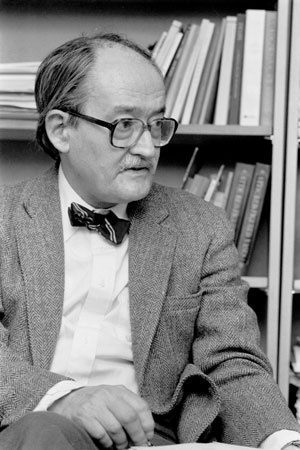

Donald Carne-Ross Photo by BU Photography

Donald Carne-Ross Photo by BU Photography

Donald Carne-Ross, BU’s William Goodwin Aurelio Professor Emeritus of Greek Language and Literature, helped usher in a new era of classical translation.

“He wanted to bring across the poetry in and of itself,” says Teresa Iverson (UNI’77,’97), Carne-Ross’s longtime companion and a former student. “He had a deep knowledge of how poetry is written and constructed, and he could bring that to bear on ancient Greek.”

Carne-Ross a University Professor emeritus and a College of Arts & Sciences professor emeritus of classical studies, died on January 9, 2010. He was eighty-eight.

He was born in Havana and grew up in England. After earning the equivalent of a master’s degree at Oxford — a process that was interrupted by military service during World War II — he took a job as a producer with BBC Radio’s Third Programme.

He developed a reputation for innovative programming. In the late 1950s, he asked several translators and poets to produce an updated translation of the Iliad, among them the poet Christopher Logue — who knew no Greek. According to a 2008 article in the Times of London, Carne-Ross dismissed Logue’s concerns.

“Read translations,” Logue recalled Carne-Ross telling him. “Follow the story. A translator must know one language well. Preferably his own.” Logue went on to translate several books of the Iliad in the same modernist style; the Times called it “the most distinguished classical project germinated by radio.”

Carne-Ross moved to America in 1959 to pursue a master’s at Cornell. In 1962, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study Italian literature. He was hired to teach at the University of Texas, Austin, a job that would introduce him to John Silber (Hon.’95), who later became president of BU.

At Austin, Carne-Ross cofounded Arion, a journal of humanities and the classics, with William Arrowsmith, a late CAS professor emeritus of classical studies. (The journal, still in publication, is now housed at BU.) Arion broke new ground by approaching the classics from a literary rather than a historical perspective. Carne-Ross and his “lively classicist” colleagues, Time magazine wrote, had “set out to banish the philological quibbling and fusty Victorian translations that have stupefied students for generations.”

In 1965, Carne-Ross and Arrowsmith founded the National Translation Center at Austin and a companion journal of translation, Delos.

When Silber left Austin to run BU in 1971, Carne-Ross was one of several professors he recruited to join him on the East Coast. The group, known as “Austin in Boston,” gained a reputation as the “rock stars of the literary world and the classics,” Iverson says.

“They wanted literature to be something that was exciting for students, and they made it exciting,” she says.

It was a heady time for BU’s classicists, she recalls. “They felt that there were things that were missing from the way Greek literature was taught.”

One of Carne-Ross’s complaints was twofold: that students of Greek language rarely read Greek poetry, while students of classical poetry rarely read the texts as poems. “He was considered something of a maverick,” Iverson says. “He had us reading Greek poetry right away. It was unusual, even for graduate students.”

Carne-Ross was best known as a critic of English translations of Greek and Italian poetry. He would often retranslate verses he thought had been watered down and made more palatable to modern readers, Iverson says, to “show the spirit that was there.

“He was formidable,” she says. “You wouldn’t want to have Donald opposing you if you were a translator.”

While at BU, Carne-Ross helped create the University Professors Program, where he taught until 2001. Over the years, he published several edited translations and works of criticism.

His 1985 edition of Pindar’s odes — long considered too difficult for a general audience unfamiliar with Greek — “opens up the work of the great Theban more clearly than anyone has yet done in English,” the New York Times wrote. “His little book could convert not only the Greekless to Pindar but the tuneless to poetry.”

In 1996, Carne-Ross published Horace in English, coedited with Kenneth Haynes. The book contained a philosophy of sorts: “The translation of the past, however much we may cherish it, cannot keep a poet alive,” he wrote. “He must be re-embodied in the speech of each new day.”

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Post Your Comment