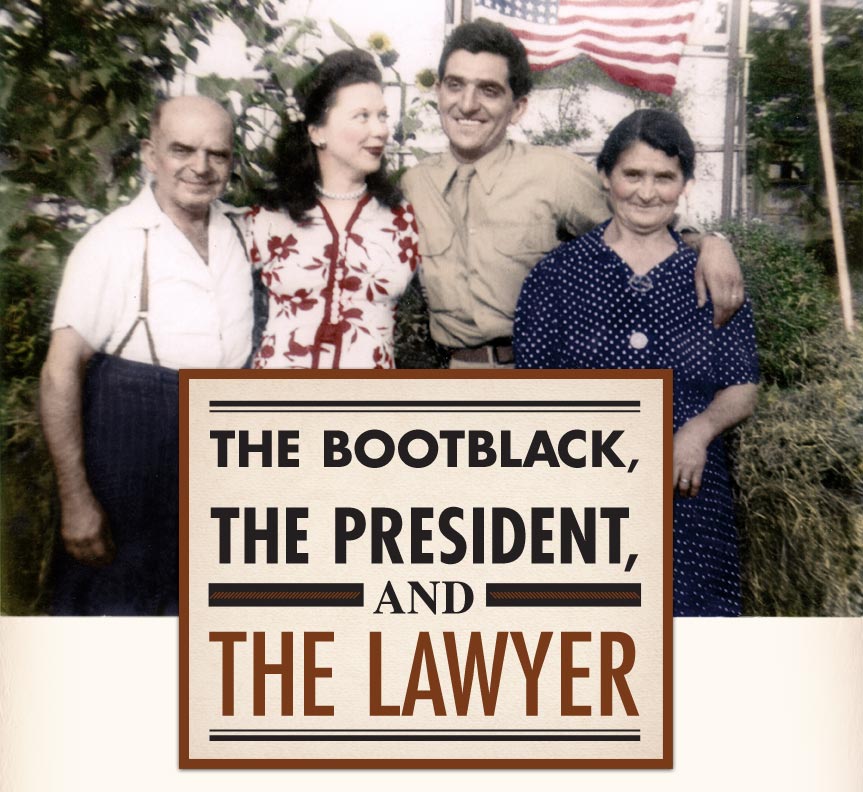

The ambition of an immigrant's son and the vote of confidence of a BU president lead to an American success story—and an endowed scholarship.

Early every morning throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Eleftherios Parasco boarded the trolley in Saugus and headed off to his job at the Lenox Hotel in Boston. Always, he was dressed immaculately: three-piece suit, watch on a gold chain, stickpin in his tie, spats, and—depending on the season and the fashion—a bowler or boater.

Eleftherios took pride in his work. He shined shoes and dispensed towels at the Lenox, back in the day when that hotel was favored by traveling salesmen, who descended on the hotel in large numbers from the Back Bay train station. Savvy salesmen knew that Eleftherios could put his hands on a pint in those Prohibition days, and he was a popular figure in the parched Back Bay.

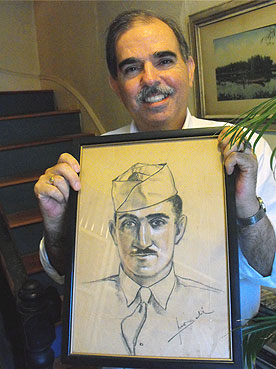

Chester Parasco Jr. holding a sketch of his father, Chester Sr.

Also in the Back Bay at that time were Boston University's central administrative offices and the College of Liberal Arts (today's College of Arts & Sciences), located in a formidable building at 688 Boylston Street, where the Boston Public Library's annex now stands. And one of Eleftherios's regular shoeshine customers was BU President Daniel Marsh (STH'08, Hon.'53).

Eleftherios and his wife, Anastasia, were Greek immigrants: he from Smyrna, and she from Sparta. They arrived in the United States separately during the 'teens and were married almost immediately—a hint that the marriage had been arranged in the Old Country. Eleftherios found work, and the couple bought a modest house in Saugus and began a family. The oldest of their three children, Chester, was born in 1918.

Chester (CAS'47, LAW'47) was a smart and handsome boy who, like his father, had ambitions. Aiming to attend a prestigious Ivy League school, he enrolled for a year of postsecondary study at Kents Hill Preparatory School in Maine. He paid for that extra year of high school himself, with money he had saved doing odd jobs. His plan worked: while at Kents Hill, he was accepted to Princeton.

Then Eleftherios stepped in. He had never heard of this place "Princeton," and he certainly wasn't going to pay to have Chester go to school there. Eleftherios insisted that Chester enroll at the local alternative—Boston University—and his reluctant son agreed. Then Eleftherios dropped the other shoe: He wasn't much inclined to pay for BU, either.

Despite waiting tables and working other part-time jobs, Chester could not pay his tuition bill and couldn't enroll for his next semester. Eleftherios shrugged off his son's request for financial help. "You have troubles?" he asked. "Go see the president—a friend to me."

Which is how Chester Parasco arrived at Daniel Marsh's office, sometime in the late 1930s. A secretary told him that he would have to make an appointment; Chester strode past her, pushed open Marsh's door, and introduced himself to the startled president. "My name is Chester Parasco," he said in his booming voice. "My father shines your shoes." Marsh heard him out, and then reached for a notepad. "Let this man move ahead," he wrote. Chester's BU education continued.

He had never heard of this place "Princeton," and he certainly wasn't going to pay to have Chester go to school there.

When World War II broke out, Chester left school, enrolled in the Army, earned the rank of corporal, and (according to family lore) was the first American to hit the first beach—at Salerno—in the Allied effort to retake mainland Europe. He subsequently received the Bronze Star for heroism.

After the war, Chester made up for lost time. Even before completing his undergraduate degree, he enrolled at BU's law school. He and a former classmate, Loretta Lynch—who earned her CLA degree in 1941—were married. At the 1947 Commencement, Chester received both his CLA and LAW degrees, and soon took a job with the legal department of an insurance company. The Parascos and their newborn son, Chester Jr., moved from veterans housing in Charlestown to a modest tract house in Walpole. After several years, Chester set up a law practice in downtown Boston with a friend—first called Parasco and Levy (today's Parasco Worthington & Chase). From his office at 53 State Street, he became associated with State House lobbyists and politicians, building a lucrative practice. "No one could work a room like my father," recalls Chester Jr. with a smile. "Nobody."

In 1963, Chester Sr. became assistant legal counsel to Massachusetts Governor Endicott Peabody. Increasingly, he turned his attention to politics and public service on the local level. He also stayed in touch with BU, attending the occasional reunion and—with his wife—making a series of small gifts to the University.

Loretta died in 1993, and Chester followed in August 2009. In his will, he included a bequest of $150,000 to establish and endow the Chester and Loretta Parasco Scholarship Fund, to support students selected by the dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. The only proviso, according to the terms of the will, is that the selected students demonstrate both financial need and academic merit—conditions that Chester himself surely met, on that long-ago day in the office of President Marsh. ■

This article first appeared in Bostonia.