Girl in Pieces: The Quasi-Subjectivity of Greer Lankton’s Dolls

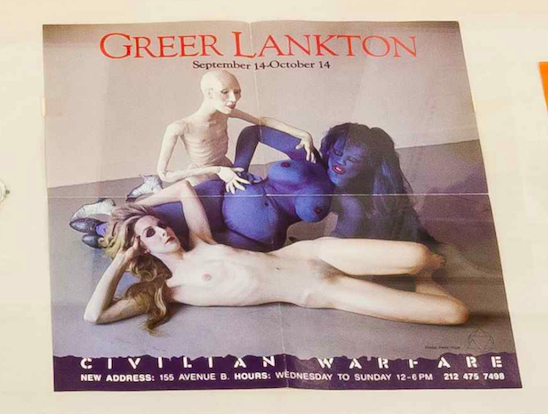

In New York’s East Village in the 1980s, visitors flocked to Einstein’s on East 7th Street to catch a glimpse into the world of Greer Lankton. What distinguished this clothing boutique from countless others were the androgynous, emaciated figures that filled its glass storefront with a kaleidoscope of strange glamour. Made from cloth, wire, and plaster, with glass eyes and real hair, Lankton’s dolls and mannequins had a compelling cult status, situated between art and commerce, high and low culture, beauty and abjection, life and artifice. After her life and career were cut short in 1996 by a fatal overdose, Lankton became marginal to art historical accounts of the 1980s. But as objects that claim some of the qualities of living subjects, Lankton’s dolls embody the fraught relationship between subjectivity and representation that was a major concern of feminist artistic discourse of her period (Fig.1).

Lankton’s dolls can be read as quasi-subjects, on the threshold between person and thing. In their anthropomorphism, they suggest the potential for subjectivity, but more significantly they act as surrogate subjects in the artist’s own production of the self. Unapologetically autobiographical in nature, Lankton’s workis deeply entangled with the politics of transgender representation. Judith Butler has articulated how gender “figures as a precognition for the production and maintenance of legible humanity”[1] within the social sphere. As a transgender woman, Lankton lived with the threat of becoming a “thing” under the normative gaze. Through the quasi-subjectivity of her dolls, the artist destabilizes the very categories of “person” and “thing.” Viewing photographs of dolls posed by the artist, acting as subjects, and of the artist posing alongside them, produces a confusion of subject-object relations similar to what Bill Brown’s study of the “thingness” of objects calls “occasions of contingency” that disrupt clear boundaries of self against Other. “The story of objects asserting themselves as things,” he writes, “is the story of a changed relation to the human subject,” [2] a changed relation that Lankton courts to reframe normative perceptions of bodily difference and gender variability (Fig. 2).

The projective capacities of the doll and its cousin, the mannequin, have been seized upon by many artists across the twentieth century. They embody the mechanized subjectivity of mass culture, the repressed and at times violent impulses of sexual desire, and, later, feminist critique of social conditioning. In the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition, dolls and mannequins embodied “both the femme-enfant, an uncanny childlike doll who evoked repressed fears and desires, and the femme fatale, who evoked lustful and often sado-masochistic fantasies,” according to Alyce Mahon.[3] However, the modernist doll was not exclusively a vehicle for masculine projections of desire, fear, and violence onto the female body. Modernists Sophie Taeuber, Emmy Hennings, and Hannah Hoch all worked with dolls. Hal Foster notes that “for these women, such figures were vehicles of role-playing, of staging and testing models of femininity.”[4]

Of particular resonance to Lankton’s work is the fin-de-siecle dollmaker Lotte Pritzel, who, like Lankton, created her androgynous figures for commercial storefronts and as art objects. Pritzel inspired Rainer Maria Rilke’s now classic essay on the doll, which explored the “doll-soul,” an excess element beyond projected fantasies, that sits on the threshold of human comprehension. He writes, “we realized we could not make [the doll] into a thing or a person, and in such moments it became a stranger to us.” [5] This life of the doll, neither object nor subject, is key to understanding Lankton’s artistic project.

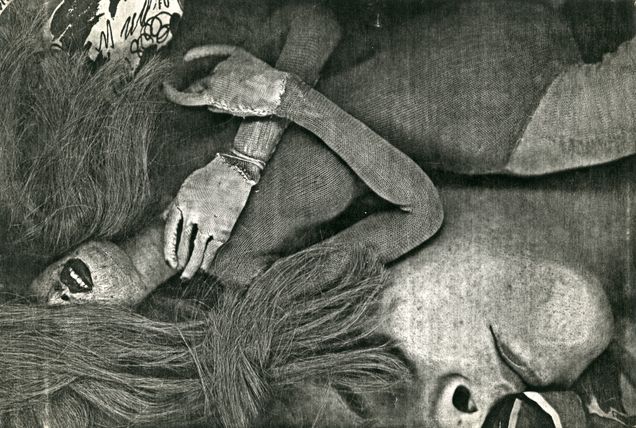

The doll’s potential to destabilize boundaries of subjectivity found its apex in the work of German artist Hans Bellmer, whom Lankton identified as her greatest influence.[6] His painstakingly crafted Poupée, composed of abject torsos and limbs connected by ball-joints, could be assembled in various configurations. While Bellmer’s work has been criticized for its disturbing fixation on the sexualized adolescent female form, the significance of his work here is in his conception of the body as mutable, inviting endless reconfiguration through its “annagramatical potential.”[7] Roxana Marcoci argues that his transformations of the doll “dispensed with the idea of the unitary self,”[8] offering alternatives to normative conceptions of the sovereign body.

Lankton’s dolls show startling parallels to Bellmer’s. Both continuously reworked, repainted, and reassembled their dolls, laboring over them for years. They also shared an obsessive desire to document the transformation and animation of their figures through drawing and photography. Like Bellmer, it is through Lankton’s posed photographs of the dolls, the ways in which she crafted their relationship to the gaze of the camera, that we learn the most about their potential inner life.

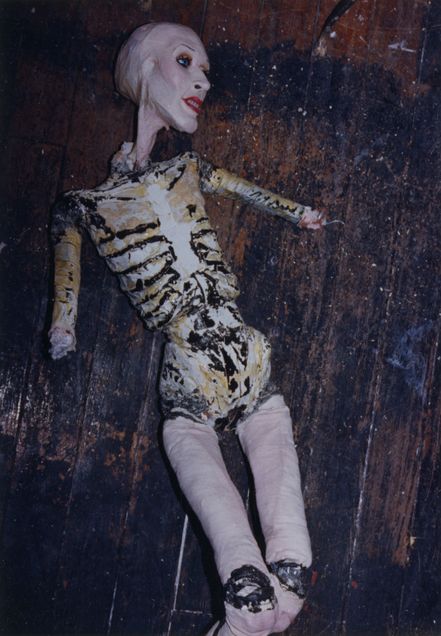

Sissy, one of Lankton’s favorite dolls and her most autobiographical figure,[9] was continually reworked for the entirety of Lankton’s career, as seen in photographs spanning nearly a decade. In one image, we see Sissy seated outside Einstein’s, seemingly taking a smoke break. In another, she is shown outside a subway station, wig removed, her pants around her ankles, her penis exposed. Another shows her lounging in a bedroom surrounded by smaller, less animate dolls. Sissy’s style of dress varies in each, as does the painted surface of her body. Previously unpublished photographs from Lankton’s archive show Sissy stripped down to her wire armature, caught in the process of disassembly, revealing the degree to which these revisions penetrated to the doll’s very core. (Fig. 3)

Lankton spoke of Sissy’s reconstructions as her “operations,” ritualized and documented by the camera.[10] Bellmer used the same term to describe his doll’s transformations.[11] In Bellmer’s case this carries an almost sinister connotation, but if Sissy is indeed a self-portrait, Lankton’s use of the term takes on different meanings. Lankton had a history of traumatic medical care in childhood, including electroshock therapy to “cure” her transgender “condition.”[12] Her sexual reassignment surgery at the age of nineteen led to months of traumatic physical recovery, which she documented in harrowing drawings. Here the term “operation” reveals a deep empathy with the position of her dolls, and a desire to reframe her medical trauma as a creative act of transformation.

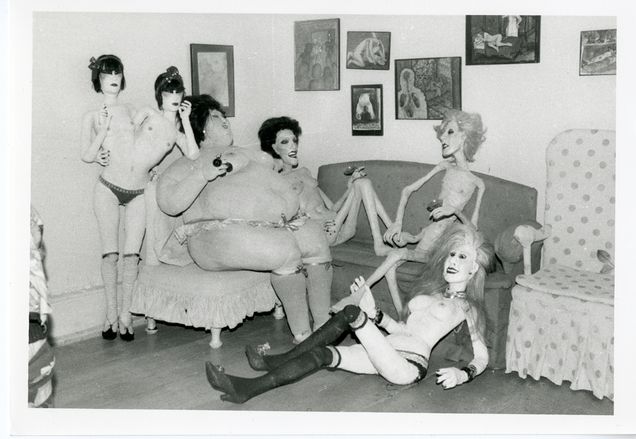

However, traumatic de-articulation is merely one aspect of Lankton’s project, just as gender dysphoria or transition narratives are merely one aspect of trans life. Her work also exudes a sense of familial intimacy, celebratory glamour, and unflagging humor. In many of the photographs she made of her dolls, she trains her camera on them as intimates, focusing on their faces, their postures, and their interactions with one another. Unlike Bellmer’s photographs of his Poupée, which appear violently coerced into position, Lankton’s dolls seem almost in control of their imaging, knowing and willful collaborators. (Fig. 4)

In his writings on feminist strategies that subvert the masculine gaze, Craig Owens identifies a “rhetoric of the pose” whereby artists adopt posing as gray zone between being passively rendered an object and actively becoming a subject. Owens argues that in such works “the subject posesas an objectin order to be a subject.”[13] To see Lankton’s sculptures as posingrather than posed is to read them as rendering themselves objects. Agency is thus granted to the dolls through their very status as objects, in a formulation related to Lankton’s complex relationship to her own image in the world as a transfeminine body. Barbara Johnson acknowledges that a founding insight of feminist criticism is “that the idealized, beloved woman is often described as an object, a thing, rather than a subject,” but argues “perhaps the problem with being used arises from an inequality of power rather than from something inherently unhealthy about willingly playing the role of the thing.” Instead, she asks: “what if the capacity to become a subject were something that could best be learned from an object?”[14] To extend this to Lankton’s practice, how does this emergence of subjectivity for these surrogate bodies through their very objecthood, their materiality, relate to an experience of trans embodiment?

An answer might be found in Peter Hujar’s portrait of Lankton posed alongside her dolls Sissy and Princess Pamela, shot for her exhibition at Civilian Warfare in the East Village. Reclining nude together, the three present a radical image of the possible configurations of femininity, or even personhood. Lankton entangles the status of her dolls as quasi-subjects with her own precarious status as a “legitimate” body in the eyes of others. She poses herself as if a doll, drawing on their liminal status between subject and object to claim the space of material and gendered indeterminacy as her own. (Fig. 5)

Understanding Lankton’s life entwined with her dolls’ provides us with new codes of intimacy, and new modes of perceiving otherness. To see objects as living subjects, to acknowledge the dissonance in this recognition and nonetheless invest empathy and care towards these objects may help us to live empathetically with difference among subjects. Jane Bennett’s understanding of the life of objects insists on “the alterity of things as an essentially ethical fact,” whereby “accepting the otherness of things is the condition for accepting otherness as such.”[15] Lankton’s dolls invite similar readings, producing considerations of self and other as always in a state of relation and becoming.

Evan Fiveash Smith

____________________

[1]Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (London: Routledge, 2004), 11.

[2]Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 1, Things. (Autumn, 2001), 1-22: 4.

[3]Alyce Mahon, “The Assembly Line Goddess: Modern Art and the Mannequin,” from Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 191.

[4]Hal Foster, “Philosophical Toys and Psychoanalytic Travesties: Anthropomorphic Avatars in Dada and at the Bauhaus,” in Art and Subjecthood,25.

[5]Ibid., 57.

[6]Greer Lankton, artist statement for It’s All About ME, Not Youat the Mattress Factory, 1995.

[7]Marquand Smith, The Erotic Doll: A Modern Fetish.(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 292.

[8]Roxana Marcoci, “The Pygmalion Complex: Animate and Inanimate Figures,” in The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1938 to Today, 186.

[9]Lia Gangitano, as told to Johanna Fateman, “500 Words: Greer Lankton,”Artforum, October 2014.

[10]Paul Monroe, “Unalterable Strangeness,” Flash Art.

[11]Wieland Schmied, The Engineer of Eros, in Hans Bellmer, 22.

[12]Monroe, “Unalterable Strangeness.”

[13]Craig Owens, “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality(New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1985), 17.

[14]Barbara Johnson, Persons and Things (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 95.

[15]Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things(Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 12.