Painting, Photography, and Radical Depictions of Gender: Franz Gertsch and Lissa Rivera

In representations of gender in art, storytelling operates on a political level by either affirming or subverting normative tropes. The artist’s power to control visibility, to selectively reveal or hide, becomes a political gesture. This paper examines the radical potential of photography and Photorealist painting within this sphere. It applies a case-study approach to read Swiss painter Franz Gertsch’s late-1970s paintings against American photographer Lissa Rivera’s ongoing photographic series Beautiful Boy. I argue that for both Gertsch and Rivera, pushing at established codes of social legitimacy and concepts of truth is an emancipatory project that challenges dominant power relations in art and society. In disrupting the dominant status quo by embracing difference as a form of political resistance, both artists construct alternative realities, imagining new worlds through art.

Photography’s ability to trouble the binary between fact and fiction can be deployed as a radical tactic for subverting rigid constructions of gender. Working collaboratively with their respective subjects, Gertsch and Rivera deploy the narrative shorthand of a portrait and the indexical associations of photography to explore the relationship between reality and fantasy. In her book Self/Image, art historian and theorist Amelia Jones writes, “the tension earmarked by aesthetics between subjectivity and objectivity is…at the core of how humans exist in the world.”[1] While many artists obscure or avoid this disjuncture, Rivera and Gertsch produce work which is consistent with what Jones categorizes as “retain[ing] rather that attempting to resolve or disavow this tension between the subjective and objective world.”[2] Invoking critic Roland Barthes, Jones notes “that representation can only deliver what we think we (want to) know about the other, who is never real but always (somewhere) Real.”[3] When it comes to cultural paradigms such as heteronormative gender categories, art can reveal the tenuous relationship between these social constructions: subject, object, and real. Making these constructions visible, Rivera’s and Gertsch’s works depict people performing a compendium of possible selves embedded in the medium.

Known for her bold colors and opulent compositions, Lissa Rivera mines the history of art and the historical conventions of painting through photography. In the series Beautiful Boy, Rivera works with her genderqueer collaborator and partner, BJ Lillis, to explore representations of the body through references to the aesthetics of classical paintings, fashion photography, and avant-garde cinema. Although conceived as a series, each composition stands alone, presenting an independent narrative. Although Lillis appears in each photograph, he performs a different role in each: a bold model, staring down the viewer; a fashionable urbanite; a downcast figure upon a bed. In aggregate, the multiplicity of images represents a variety of gender expressions of one body. They show that the self is never static, but rather, context-specific, fluid, and unconstrained.

A political project underlies the arguably seductive visual appeal of these saturated colors and sumptuously detailed backgrounds. In an interview for this essay, Lillis described his perception of viewers’ responses to the photographs. He noted:

They like them already before they have time to think about their own politics or how they might feel about what we’re doing on the political level. By the time they even register my genderqueer-ness, they already like the photos because of the colors and the way that they’re composed.[4]

By putting into circulation easily-appealing photographs of an individual whose marginalized identity is not immediately apprehensible, Rivera and Lillis play with the viewers’ expectations of the image, while simultaneously commenting on the political and aesthetic possibilities of the photographic medium. For Rivera, the process of their photographs’ integration into mass visual culture through the internet, print publications, and exhibition spaces is political because it serves to balance pervasive depictions of bodies that conform to rigid gender-norms.[5] When interviewed for this essay, Rivera also noted that, “BJ is able to express this Baroque version of femininity that I could never express myself. In a way, he’s dressing up as my fantasy self.”[6] Thus, Rivera and Lillis explore gender as a construct, using staged performance to work through various depictions of both their gender expressions.

Gertsch’s large format Photorealist paintings from the 1970s explore the potential for remediation in photography and painting through the depictions of his frequent portrait subject, friend, and fellow artist, Luciano Castelli. His three-part sequence of paintings, At Luciano’s House (1973), Barbara and Gaby (1974), and Marina Makes Up Luciano (1975), is especially evocative. Derived from three photographs taken on the same day, the three paintings depict a group of the artist’s close friends, named in Gertsch’s titles. By selecting three distinct moments from the same evening, the artist invites the viewer to imagine a narrative, leaving open the possibility of interpreting these compositions along different story arcs.

Unlike Rivera, who only uses natural light and long exposures, Gertsch utilized a bright flash to photograph these indoor situations. The resultant stark contrast and sharply outlined, saturated silhouettes of the source photographs heightens the desired hyper-real style of Gertsch’s paintings. By mimicking the effects of a short focal length and close cropping, these paintings reproduce the formal characteristics of voyeuristic and unposed snapshot color photographs. Yet, due to their large size and Gertsch’s meticulous attention to detail, the paintings were completed over a three-year period.[7] This paradoxical elongation of time—from a momentary flash to a prolonged painting project—lends tension to the relationship between the photographic and painterly in Gertsch’s Photorealist paintings.

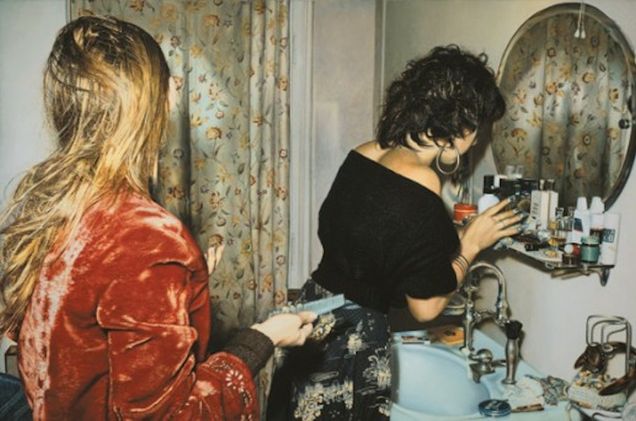

Like Rivera’s portraits of Lillis, these group portraits by Gertsch also deeply engage with the politics of gender. The painting At Luciano’s House shows the group in Castelli’s home as they dress for a party. Marina (as identified in another painting) is caught in motion as she either puts on or removes a jacket, her hands clutching the lapels while she looks at something outside the frame. The next painting, Barbara and Gaby, follows an implied course of events that evening as the friends apply makeup and style their hair using an abundance of toiletries. In this painting, the two figures stand with their heads turned toward the mirror, concealing their faces. They are nevertheless coded as female bodies, their hairstyles, clothing, and grooming accessories functioning as the culturally-constructed identifiers of femininity.

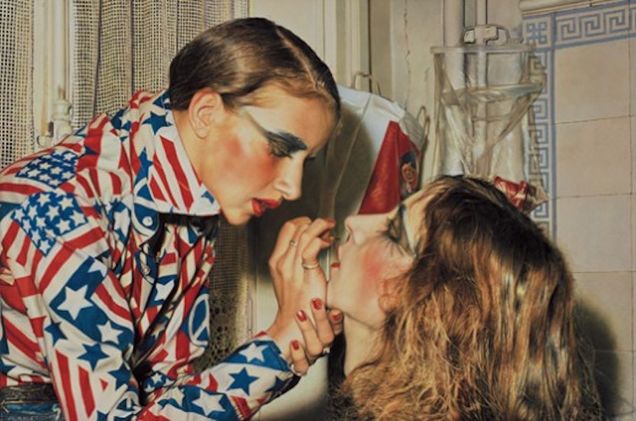

In the third and final painting of the sequence, Marina Makes Up Luciano, Gertsch complicates this normative portrayal of gender expression. Marina is poised above Castelli, the closely cropped composition accentuating the action of the painting: her finger smudging the crimson lipstick on his lips. Gertsch emphasizes the frozen motion of her hand by centering the two figures within the close framing of the image. Castelli’s face is turned upwards toward Marina. She stabilize one of her hands with the other, bracing it against his chin. With their makeup applied identically—the heavy eye shadow, elongated black eyeliner, and radiant red blush—they seem like reflections of each other. The overall mirroring effect of their makeup, tandem poses, and matching facial expressions produces an uncanny doubling effect. Paradoxically, they are at once similar yet distinct. The assertion within the title—that Marina “makes up” Luciano—suggests that she does more than apply makeup to his face. In a strongly evocative way, the title implies that she somehow “makes up” Luciano in the sense of conjuring a fabrication, thus hinting at and blurring the binary distinction between fiction and reality in the painting. The ambiguous and constitutive nature of their gender identities is part of the point.

When viewed together, the works of Rivera and Gertsch prompt us to consider gender and identity as boundless constructs. Comparing Gertsch’s Marina Makes Up Luciano with Rivera’s Boudoir (2015), we can see how both artists embrace the interplay between truth and performativity. Each composition purports to capture a moment of action, frozen in time, as the subject is transformed through the gesture of the hand within the frame. In Boudoir, Rivera’s gloved hand reaches into the space of the photograph to smooth Lillis’s hair with a brush. The artist’s involvement reveals the carefully-staged nature of the work. The tension between artifice and performativity is embraced, not resolved or concealed. This interplay of subjectivities and mediums that occurs in both Marina Makes Up Luciano and Boudoir is reminiscent of what Jones terms “the contingency and embeddedness of the self on/in the other.”[8] Both works show how gender and identity are not individually constituted, but socially constructed. Gertsch and Rivera offer us a way of conceptualizing gender through the complex relationship between photography, painting, and performativity.

Maria V. Garth

____________________

[1] Amelia Jones, Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (London: Routledge, 2006), 10.

[2] Ibid., 10-11.

[3] Ibid., 248. See also Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 1981).

[4] B. J. Lillis, interview with the author, February 10, 2019.

[5] Lissa Rivera, interview with the author, February 10, 2019.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ulrich Loock, “Group Portraits from the Early Seventies,” in Franz Gertsch: Retrospective, edited by Franz Gertsch, Reinhard Spieler, and Samuel Vitali (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2006), 113.

[8] Amelia Jones, Self/Image, 10.