Revisioning the Dead Body: Green Death

Are we human? With the aim of observing the invention of the “human” category in historical layers, the Third İstanbul Design Biennial (2016) regarded the simple yet bizarre question as simultaneously urgent and ancient. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, curators of the Biennial, conducted an archeological excavation that extends from the smallest subatomic level to the furthest point in outer space, where Voyager—the probe advancing one-million miles every day since 1977—has reached. As their archeological site, they have selected that of “human,” and all that it touches. This infinite stretching of the human sphere was the subject of the iconic 1977 Powers of Ten video by Ray and Charles Eames, zooming 1016 meters inwards and 1024 meters outwards. The Powers of Ten are actually the powers of the human, with all its ascending (and descending) skills.

As Colomina and Wigley point out, design is the reverse operation of archeology: it looks forward for all possible futures, whereas archeology tries to retain the possible pasts. [1] But to compile an anthology of all possible futures ever dreamt of, one must consult archeology. Instead of focusing on the last two years of design, this biennial focused on the phenomenon of design—which is the same age as Homo sapiens. It examined the human as an entity who lives in its own design “like a spider lives inside the web constructed from inside its own body.” [2] Stretching from the human’s two-second-old social-media representations of itself to its two-hundred-year-old industrial design adventure, the biennial contained the entire two-hundred-thousand-year-old human experience on earth. By becoming a multimedia documentary of the human, the 3rd İstanbul Design Biennial was liberated from biennials’ two-year protocol. Perceiving design as a geological layer on earth, the biennial indicated that our daily lives consist of the “experience of thousands of layers of design that reach to outer space but also reach deep into our bodies and brains.”[3] All is designed, “from our carefully crafted individual looks and online identities, to the surrounding galaxies of personal devices, new materials, interfaces, networks, systems, infrastructures, data, chemicals, organisms, and genetic codes.”[4] There is no place design hasn’t touched. It has permeated the everyday circulation of organic and synthetic systems. The heat, movement, and chemistry of all water has been affected.[5] Even the most ordinary breath taken in a city has an “ingredients” list, one likely containing pasta-water vapor, deodorant, fly-repellent spray, and smoke.

In the little book published as a part of the biennial by Lars Müller Publishers, there is a photograph by Chris Jordan of a dead bird body washed up onto the shore on a reef in the North Pacific.[6] It also has an ingredients list: plastic-bottle caps, plastic-fork pieces, dowels, and plastic-bag remnants. It comes as no surprise that many species face habitat loss and extinction due to environmental pollution and overhunting—realities designed by humans. As the biennial manifesto attests, “design is even the design of neglect,”[7] and this type of design can take interesting forms. There are, of course, more explicit forms of human-designed domination. Like other omnivorous species, the human feeds on animals. Unlike other omnivores, it also turns dead animal bodies into products. In other words, the human designs them. With a toolset it has perfected, the human even designs alternatives to the operation of hunting. Homo sapiens breeds the animal it utilizes, conserving time and energy in food production, while designing operations to prevent other animals from hunting those bred animals. It even breeds different animals to herd those to be utilized and develops chemicals to harm animals that might in turn harm the food production.

The newest operation designed by the human is artificial intelligence to manage all its other operations. Farms have turned into digitized and even digitalized industrial settings that use the animal body as raw material. That body might have to go through genetic modifications in order to become a desirable product with a high profit margin—the process of designing the dead animal body starts before it is born. Once born, it receives love and heat from incubators. But while growing up, the animal body is also exposed to artificial illumination that stimulates its pituitary gland and speeds up the process of reaching sexual maturity and fertility, tricking the body into utilizing its full genetic capacity. After reaching sufficient growth, it is killed, plucked, broken into pieces, and packaged. Robots (humans’ faithful terminators) then create schnitzel packages out of dead chicken bodies. For those few tasks that robots can’t accomplish, “unqualified” human workers are used, who then imitate the robots with their bodies and souls. For many city dwellers, besieged by human artifice and fed by grocery products, the first image that the word “chicken” alludes to is this packaged version of its dead body, or even just the body after it is cooked.

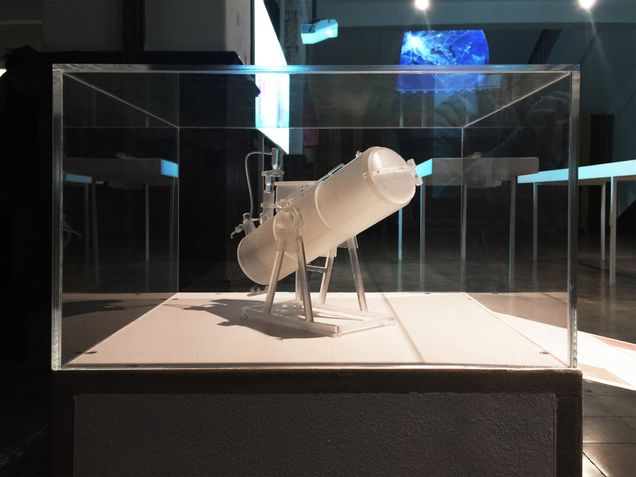

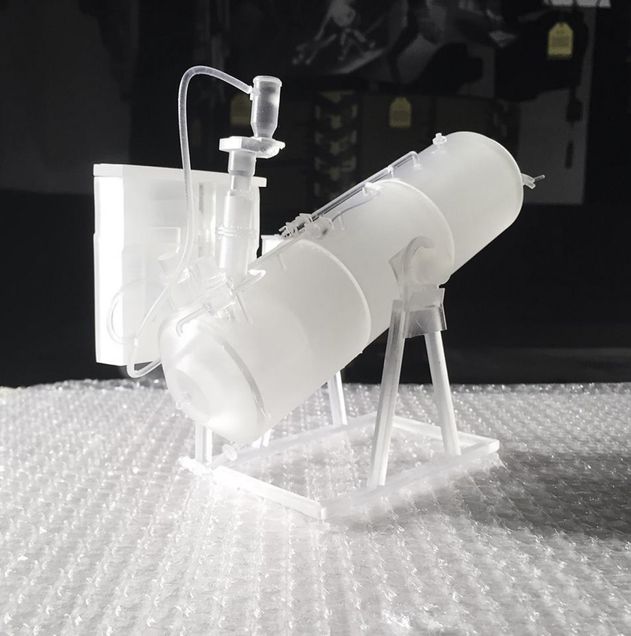

What about the dead human body? In an age of maximum efficiency, dead humans turn into something to be utilized as well: bio capital. (Or bio waste?) In a rather concealed area of the biennial’s large installation “Going Fluid: The Cosmetic Protocols of Gangnam” (2016), the architect duo Common Accounts placed a small-scale model of the LT-28, or the Alkaline Hydrolysis System for Human Disposition. This system dissolves the human body in a lye solution into a nutritious mixture for plants, leaving otherwise only bone fragments. By replicating the normal decay of the human body within just a few hours, this new technology goes beyond just introducing a new death custom—it presents a brand-new understanding of time after death. The sudden transmutation of the dead human body into a fertile object asks questions about the status of that body at a pivotal moment in humanity’s history of exchanges with nature. Originally an animal-waste service, alkaline hydrolysis is now employed by Homo sapiens to dispose of the human body not just for its own benefit, but for the benefit of all organisms. Also known as resomation, bio-cremation, or green cremation, alkaline hydrolysis has a far smaller carbon footprint than regular cremation. It is the eco-friendliest post-mortem option yet—except, perhaps, Buddhism’s sky burial, where the body is broken up and fed to vultures until there are only bones left, or Zoroastrianism’s Tower of Silence, a structure designed for bodies to be left to decompose and be consumed by scavengers. Compared to these options, the modern alkaline-hydrolysis process is perhaps quieter and cleaner, although only based on the sterile contemporary conceptions of hygiene. Regardless, whether under the soil, above in the sky, or encased in steel machines, human bio capital is food for other organisms.

The limited capacity of current burial and cremation practices and the rising anxiety regarding the adverse environmental effects of most traditional body-disposal methods has pushed humans to consider alternatives like this one. If the alkaline-hydrolysis process becomes prevalent, there will be nutritious liquids systematically flowing and spreading everywhere, leaking into the terrestrial globe, into our space and our living beings—a brand new layer of design, still in flux, demanding interrogation in varied spheres of meaning. This is exactly why Common Accounts used the phrase “Going Fluid” for their installation title. It explored the alkaline-hydrolysis process but also the growth of body-designing in the titular Gangnam neighborhood. As the home base of South Korea’s thriving plastic-surgery industry, Gangnam’s urban texture is being redesigned in order to accommodate a human population that is also being surgically redesigned. As another method of body processing, alkaline hydrolysis is similarly redesigning its immediate environment, changing how humans dispose of dead human bodies and how we organize the spaces of our cities.

If cemeteries are considered as functionless spaces that contradict with the hygienic ideal of the modern city, it is also possible to think of alkaline hydrolysis as a continuity of the “good design” tradition. A world released from religion makes it possible. Theorist Michel Foucault claimed that the category of time was released from its religious sanctity in the nineteenth century, though the desanctification of space has been more obstinate.[8] Cemeteries remain contested, semi-sacred spaces—or, as Foucault terms them, heterotopias. This partial desanctification allowed for cemeteries to be moved from the heart of the city, next to churches, and into the periphery, as death increasingly becomes viewed as a disease, something that could be transmitted to the living.[9] Is alkaline hydrolysis the final stage of this desanctifying process? Still—it must be acknowledged that our world faces an increasing lack of space. Even Foucault draws attention to the practical problems of body classification, storage, and circulation in modern cities.

The increasing obsession with hygiene, the expanding metropole population and corresponding lack of space, the dissolution of certain spaces as sanctified, over-industrialization, the obsession with maximum productivity, and ever-growing ecological concerns might explain why a design like the alkaline-hydrolysis process has emerged. Nonetheless, potent criticisms remain: From a religious standpoint, is the process disrespectful to human bodies? The consideration of human bodies as waste, excess, or disease is also controversial in secular schools of thought, which place the human body at the center of the universe. A thousand years before Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, done in 1490, there was Vastu Shastra, a scientific piece in Sanskrit, which viewed the human body both as microcosm and macrocosm and took it as a base to decide on the location, function, height, and construction order of the construction elements.[10]

When considered as part of the “human-centered” design approach, alkaline hydrolysis is radical. The human’s newest design might be an important sign of a paradigm shift regarding the status of the human body. Can turning fresh human corpses into plant food supplant the transformation of fossils into petroleum-based products? If design is indeed the reverse operation of archeology, it should keep excavating for better futures, no matter how gloomy the contemporary setting might be.

A longer version of this essay was published in Turkish at Istanbul-based online publication Manifold on April 4, 2017: https://manifold.press/olu-beden-tasarimi-yesil-olum

Ecem Arslanay

____________________

[1]Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archeology of Design (Zürich: Lars Müller, 2016), 10.

[2]Ibid., 9.

[3]Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, “Theme: The Design of the Species: 2 Seconds, 2 Days, 2 Years, 200 Years, 200,000 Years,” Are We Human?, 3rd İstanbul Design Biennial, accessed November 7, 2019, http://arewehuman.iksv.org/exhibition/.

[4]Ibid., 9.

[5]Ibid., 12.

[6]Ibid., 14

[7]Colomina and Wigley, “Theme: The Design of the Species,” http://arewehuman.iksv.org/exhibition/.

[8]Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, (October 1984): 1–2.

[9]Ibid., 5–6.

[10]Colomina and Wigley, Are We Human? (Zürich: Lars Müller, 2016), 146.