Study shows promise of alternative treatment for alcoholism

MED professor a principal investigator on largest study its kind

For the past five years, researchers across the country have been studying the effectiveness of two treatments for alcoholism, one using intensive therapy and the other using a combination of less intensive therapy and drugs. The results were published yesterday in the Journal of the American Medical Association: a drug called naltrexone combined with certain types of light therapies is just as effective as a strict regimen of intensive therapy.

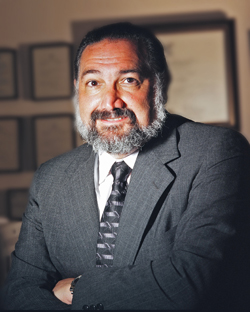

“When we designed this study, I think we all thought that intensive psychological intervention would be superior,” says Domenic A. Ciraulo, a Boston University School of Medicine professor of psychiatry and department chairman, a principal investigator in the study. "The findings are a surprise to us."

Ciraulo designed the protocols and directed the Boston-based portion of the study, which compared abstinence rates of patients who took naltrexone and were treated with a less-intensive type of therapy with those patients who underwent intensive therapy and no drugs and another group who were given a placebo. The results showed that those patients on naltrexone who also participated in 20 sessions of alcohol counseling led by a behavioral specialist were just as likely to recover as those who were treated in a more intensive and specialized alcohol counseling program, but not taking medication.

The study, Combining Medications and Behavioral Interventions for Alcoholism, was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, which is part of the National Institutes of Health. Also known as the COMBINE study, it began in five clinics, including a clinical research program in alcohol and drug addictions at MED, and was later expanded to include 11 academic sites. The study followed the treatment of 1,383 patients, and is the largest clinical trial ever conducted of pharmacologic and behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence.

Ciraulo says the study offers more hope for patients who resist or cannot afford intensive therapy. “Most people diagnosed with alcoholism are diagnosed by their primary care doctor,” he says. “There are barriers to getting into [specialized alcohol treatment] programs. We think it’s a matter of choice. Some people would rather go to counseling and see a psychotherapist; some would rather have it managed in a medical setting.”

The less-intense form of therapy given the patients on naltrexone is called medical management, Ciraulo says. It is a medically based approach designed like the educational care that diabetics receive from their doctors, and it could be performed by nurses in primary care clinics for 20-minute sessions, after an initial 45-minute session.

Ciraulo points out that the findings do not suggest that alcoholism can be treated with a pill instead of therapy. “I think it’s clear that the pill works best in the context of medical management,” he says. “It’s very powerful because you develop a relationship with a person who gives solid advice and direct feedback about the medical consequences of drinking and offers resources on how to cope.”

The barriers to making this model of care available, he says, will depend on its cost, and on whether health-care providers can be reimbursed for the work. A 45-minute visit with a nurse or a doctor is much longer than a standard appointment, he says, but if it helps people as well as the study purports, it will pay off in the long run.

The study was conducted by 19 researchers at U.S. universities, led by Raymond F. Anton at the University of South Carolina and Stephanie O’Malley at Yale University School of Medicine.