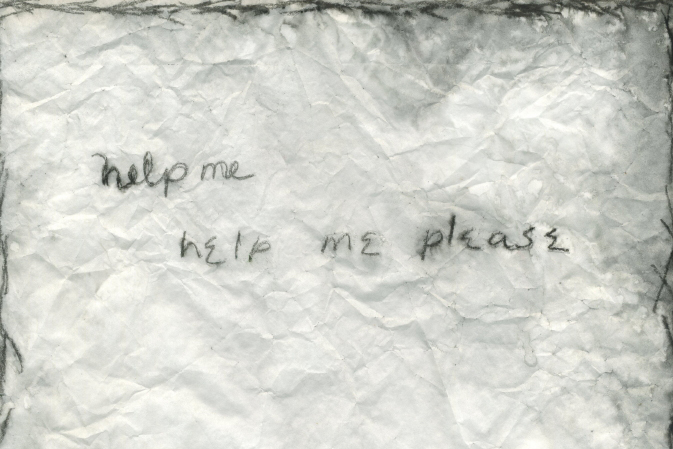

Preventing Teenage Suicide

BU-aided study raises hope and questions

A recent study of teenagers who planned or attempted suicide found good news and bad news—55 percent had received some therapy, but it failed to blunt self-destructive impulses.

The question haunts any parent whose child has taken her own life: could we have prevented it?

A recent study of teen suicide by researchers at BU and other schools reveals both the horizon of hoped-for prevention and some questions about how we get there. Of teenagers who planned or attempted suicide, 55 percent had received some therapy—good news in that they had access to services, but bad news because those services failed to blunt self-destructive impulses. And some of the illnesses those suicidal teens were being treated for might surprise readers.

The study, led by Harvard’s Matthew Nock (CAS’95), who was assisted by Jennifer Green, a School of Education assistant professor of special education, was published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry. It involved interviews with more than 6,000 teenagers nationwide and at least one of their parents. Green, a clinical psychologist who studies the role of schools in identifying emotional and behavioral disorders in young people, cautions against leaping to conclusions about the mental health treatments received by the teens in the study.

“Our measure of services was pretty general,” she says. “We really don’t know about the type of services they received or who they received services from. It may be that they just met with a mental health provider one time or that the quality of the services was not good.” Indeed, the news could be a case of the glass half-full, she says: “We don’t know how many more youths would have been suicidal if they had not had the services.”

BU Today spoke with Green, a new mother herself, about the findings.

BU Today: Media coverage of your report focused on more than half of suicidal teenagers receiving therapy before thinking about or attempting suicide. Was that the big takeaway?

Green: That was one. There were several other findings. We were able to confirm the rates of suicide ideations or behaviors that researchers have come out with using smaller samples: 12 percent of adolescents had suicidal ideation, 4 percent had suicidal plans, and 4 percent reported attempting suicide. Also, most of the adolescents who had suicidal behaviors had a mental disorder, primarily prior to those suicidal behaviors, and for the most part, those disorders are predicting suicidal ideation. So adolescents who have depression, but also attention disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, are more likely to report subsequent suicidal behaviors.

The third finding was that those mental disorders primarily predict suicidal ideation. A smaller number predicted suicidal attempts and plans. That smaller number of disorders are depression but also disruptive behavior disorders—acting out and attentional disorders, which people don’t always think of as being associated with suicidal behaviors. Those are important disorders for clinicians and families to be thinking about when they’re thinking about youth at risk for suicide.

I’m guessing that when laypeople think of teen suicide, it’s that the teen must have been bullied or had some experience that triggered it.

These mental disorders are strong predictors of suicide, but we didn’t, in the study, look at disorders as compared to social problems like bullying. So I can’t speak to whether disorders are stronger predictors than bullying or other social problems or familial factors.

Why isn’t there more effective therapy for these mental disorders in teens and why isn’t the therapy they’re getting better at averting suicide?

We really don’t have any evidence-based treatment for suicide and suicidal behavior among adolescents. We need more research, and we need to know more about how to effectively treat adolescents who are suicidal. There are evidence-based treatments for depression, anxiety, and disruptive behavior disorders—some of the disorders that predict suicide. A lot of studies specifically exclude adolescents with suicidal ideation, and just focus on adolescents with a disorder without suicidal ideation, because treatment is more complicated and could be different when you’re suicidal. There are evidence-based treatments for adults that decrease suicide reattempts, but those haven’t been well tested in adolescents yet.

What are those effective adult treatments?

The ones that seem most effective are dialectic behavior therapy, a treatment for personality disorders. It’s supposed to reduce self-endangering behaviors. Some cognitive behavior therapy has been shown to be effective for adults.

Can we learn anything from other nations’ treatment?

We really don’t know much about what other countries are doing. One of the take-home messages is we need more research, we need more clinicians and clinical researchers who are specifically studying suicidal adolescents and are focusing on how to identify adolescents who might be suicidal—how to do effective risk assessments and evaluations.

Sounds like we need more money to pay for those things.

There have been a lot of cutbacks in research funding. There are foundations and groups who are committed to doing research on suicide and on youth suicide, but more funding for this area could do a lot to make sure that youth who are suicidal get the treatment they need.

Is there anything parents can do to get a jump on this problem in their children?

Make sure that they’re evaluated and they have access to health services. It’s not just about adolescents saying that they’re suicidal, but recognizing that other disorders should be recognized and taken seriously as well. Youth who seem to be struggling for any number of reasons should be evaluated and supported.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.