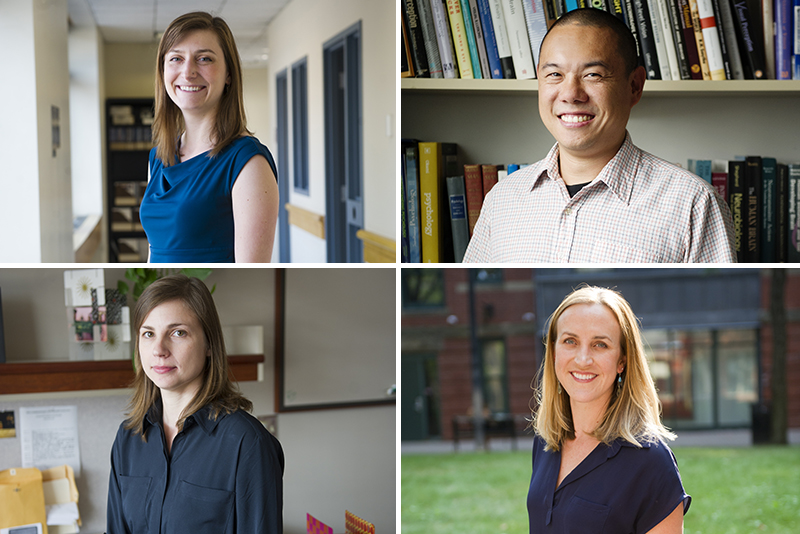

Four Junior Faculty Awarded Peter Paul Professorships

Cited for exceptional accomplishments in their areas of study

Four young BU scholars have earned this year’s Peter Paul Professorships: Jennifer Talbot (top left), biology, Sam Ling (top right), psychological and brain sciences, Elizabeth Rouse (bottom left), organizational behavior, and Angela Robertson Bazzi (bottom right), community health sciences. Photos by Cydney Scott

Junior faculty at Boston University engage in a constant juggling act, balancing the demands of teaching with research and grant and publishing deadlines. That juggling act just got a bit easier for four young faculty who each have published important research and won strong reviews for their teaching. They have received the 2015 Peter Paul Career Development Professorships, awarded annually to promising junior educators emerging as leaders in their fields. The professorships provide a three-year, nonrenewable stipend to support scholarly or creative work, as well as pay a portion of recipients’ salaries.

The 2015 Peter Paul Professorships have been awarded to Angela Robertson Bazzi, a BU School of Public Health assistant professor of community health sciences, Sam Ling, a College of Arts & Sciences (CAS) assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences, Elizabeth Rouse, a Questrom School of Business assistant professor of organizational behavior, and Jennifer Talbot (CAS’04), a CAS assistant professor of biology. The professorships are made possible by a gift from BU trustee Peter Paul (Questrom’71) and are given to junior faculty across the University.

“Professors Bazzi, Ling, Rouse, and Talbot showcase the diversity, caliber, and depth of rising talent we have on faculty at Boston University,” says Jean Morrison, University provost and chief academic officer. “From HIV prevention and the mechanics of ecosystems to the creative process and our understanding of the brain, all are making tangible, substantive impacts in their fields and brilliantly demonstrating the promise we saw in them when we welcomed them to our academic community. We are excited for what their futures hold, and pleased to support them as they pursue their research and scholarly careers here at BU.”

As a group, the honorees showcase a diverse range of academic and research pursuits.

Delving into the ground beneath our feet

For Talbot, a microbial biologist, the ground beneath our feet presents a world of opportunity to understand the future of our planet.

Her research focuses on how climate change and other factors, such as pollution and drought, affect the interactions among millions of species of fungi, and in turn affect the structure and health of the ecosystem. Talbot’s ultimate goal is to include findings about these underground interactions into predictive models about the Earth’s ecosystem that may produce insights about the Earth’s future.

She says the land surface portion of land-climate models varies greatly when projected into the future. “If you project all the models we have now out for 100 years and 500 years, they go in all different directions,” says Talbot, a chemistry major at BU who went on to earn a doctorate in biological sciences from the University of California at Irvine and do postdoctoral research at Stanford. “We want to put microorganisms into those models.”

Supported by a National Science Foundation grant, she has been studying the interactions between microorganisms. She says the Peter Paul Professorship will provide an important boost to her research by enabling her lab to create simulations of changing environmental conditions—for example, by dumping fertilizer on fungi.

Observing the decomposition of these fungi—which look like beautiful mushrooms in her lab website photos—can help us to understand what our environment will look like many years from now, Talbot says, and at the same time, it’s “opening up a new universe of organisms in the Earth’s microbiome. We’re discovering a new species every day, mapping them on the Earth, where they live, why they are there, and what it means for us.”

What we see and how we give it meaning

Computational neuroscientist Ling is working to understand how we see. And to hear him talk about his research into vision and attention is to understand that there is a lot going on in the moments between our seeing an object and assigning importance to it.

Say you are walking on a sidewalk. On the periphery, you notice that a bicyclist may collide with you. As a result, you step aside.

The workings of our brain “boost the strength of the representation of that object,” says Ling, who joined BU in 2014. “Our lab is trying to understand the mechanistic underpinnings that give rise to this enhancement.” That includes research into how the brain transforms light into interpretable meaning and how we can assign relative importance to many objects that enter our field of vision.

“The beautiful thing about visual perception is that we have decades of research in visual neuroscience, and they have done a great job of mapping out some of the core properties in vision,” Ling says. “But that is not to say we have vision cracked.”

That leaves room for inquiry. A paper he coauthored in March 2015 in Nature Neuroscience questions an established model of the primary visual cortex developed in the late 1950s. Using MRI studies, he and his colleagues found evidence that certain key processes in visual perception occur earlier than previously thought, in a part of the brain called the lateral geniculate nucleus.

The Peter Paul Professorship means that Ling, who earned a bachelor’s at Pennsylvania State University and a doctorate at New York University and did postdoctoral work at Vanderbilt University, can pursue more ideas. “There are some topics that would be interesting to explore, that are anchored in what our lab does, and that without some sort of extra resource would not be possible,” he says.

The creative process

Elizabeth Rouse brings her experiences as an artist, a manager, and a scientific researcher to her examination of the ways creative people develop ideas and share feedback—and what organizations can learn from them.

Her creative and business experiences inform her academic choices. Trained in ballet, she performed modern dance in college. She studied brain and cognitive sciences as an MIT undergrad, worked as a researcher at McLean Hospital’s brain imaging center, and was managing director of Anna Myer and Dancers in Cambridge. “I still had this craving for research,” Rouse says, “and I wanted to combine that interest in the creative process and some of the issues I saw in nonprofit organizations and arts organizations.”

Rouse, who holds a doctorate in management and organization from Boston College, joined the BU faculty in 2013. She studies artists as well as software engineers, designers, and entrepreneurs—an extreme form of creative worker, she says. In one study, Rouse and a coauthor found repeated back-and-forth feedback is more effective in the creative process than traditional top-down performance reviews.

Kenneth Freeman, professor and dean of the Questrom School of Business, says Rouse’s research publications are “beyond outstanding” and that the popular and business media are starting to pay attention to her work as well. He says that she has also received strong ratings for her teaching of the undergrad organizational behavior course.

The Peter Paul Professorship is a welcome validation of her efforts, Rouse says, and she hopes to use it to support her field research into the workings of organizations. “You never know how your work is having an impact. It feels really nice to have some assurance that it is,” she says.

Love, trust, and their relation to infectious disease

In her research into infectious diseases, Angela Robertson Bazzi often uses words like “love” and “trust.” It is these feelings that drive human behavior and that bring Bazzi to neighborhoods where the populations are more likely to contract diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C.

“We have great health promotion programs and interventions, but oftentimes there are segments of the population that are difficult to reach and don’t experience the benefits,” says Bazzi. “My work is interested in how social relationships and social marginalization impact health outcomes and access to public health services.”

Her research focuses on groups such as sex workers and their partners and other populations with substance use problems that are often underrepresented in the scientific literature. She is working to fill in such gaps. She and colleagues published a study in August 2015 in the American Journal of Public Health that focuses on female sex workers and their noncommercial intimate male partners in Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. “We found that emotions seem to play importantly in sex workers’ decisions to use condoms and other health services, so their emotional connections in their intimate relationships featured very prominently,” says Bazzi, who earned a bachelor’s at the University of Southern California, a master’s in public health at Johns Hopkins University, and a doctorate in global health at the University of California at San Diego.

Typical of her research, the Tijuana study reflects an interdisciplinary approach that combines both qualitative and quantitative techniques. For example, she worked with a medical anthropologist to test the usefulness of survey instruments that were originally designed for middle-class couples in the United States.

Like the other 2015 Peter Paul Professors, Bazzi was surprised by the award. “This will open up really important opportunities and possibilities that maybe I had been thinking about,” she says, “but this helps me think about them more concretely.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.