Medical Campus Volunteers Brave Polar Vortex to Help Boston’s Homeless

Mayor to participants: “Every person you meet out there is loved by somebody”

At 10:30 pm January 30, it was dark on the streets of Boston, and bitterly cold. Mayor Martin Walsh had just kicked off the 39th annual Boston homeless census, telling more than 300 volunteers at City Hall that their work was important—that they would be gathering valuable data in the fight to get people off the streets for good. He gave a shout-out to public safety officials, first responders—and even to a group of BU students, who had been joining the census for a number of years. This year, with Harold Cox, a School of Public Health associate professor of community health sciences and an associate dean, leading the way, the Medical Campus had dispatched some 15 volunteers.

The Northeast was locked in a polar vortex, and Walsh warned everybody about the dangerous wind chills. Anyone sleeping outside risked death.

“When you’re out there tonight, remember that every person you encounter has a story,” Walsh told the volunteers, who would fan out in 45 teams across the city, combing subway platforms, parks, building doorways, and alleys to count homeless people, and offer them shelter. “Remember that every person out there is loved by somebody.”

And it’s a lot of people. In 2018, the number of people across Massachusetts who experienced homelessness at some point was 20,068, according to a report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. That marked the highest level since 2013. The report also said homelessness jumped 38 percent in the last decade despite aggressive steps to reduce the count. One especially alarming figure was that the number of people ages 18 to 24, without children, who experienced homelessness rose 11 percent.

Harold Cox, an SPH associate professor and associate dean for public health practice, has volunteered for Boston’s homeless census for many years. Cox directs SPH’s Activist Lab, whose students work closely with the homeless and on other social justice and advocacy projects.

The count begins

Now, just minutes after their group left City Hall, heading toward TD Garden (their coverage area stretched from just beyond City Hall Plaza to North Station), one SPH student, Mackenzie Bullard, along with three classmates and Wendy Heiger-Bernays, an SPH clinical professor of environmental health, was approached by a man weaving his way down a frozen Cambridge Street, his thin leather jacket open to the subzero wind chill. His gloveless fingers clutched the stub of a cigarette.

“Do you guys have a light?” asked the man, who appeared to be intoxicated.

“I’m Mackenzie,” said Bullard, who has worked closely with the homeless through SPH’s Activist Lab. Unfortunately, he told the man, none of them had a light. “We’re with the homeless census,” Bullard said, introducing the group. “It’s really cold out there tonight. Do you need a place to stay?”

The ferocious winds made it hard to hear—or talk.

“Got a light?” the man repeated.

Bullard offered again to help him get inside.

“Got a light?” the man asked.

Back and forth it went. The homeless man—he said his name was Bobby—headed into the street, dodging a couple of cars. Concerned for his safety, Bullard and SPH student Rafik Wahbi, an Egyptian immigrant who has been volunteering with the homeless since he was 14, followed close behind. All the students had received training from SPH in how to safely connect with homeless people on the street. Earlier, in a meeting at City Hall, their team leader, Katie King (College of Arts & Sciences’06, School of Public Health’13), deputy director of Boston’s Intergovernmental Relations office, had reminded them to respect each person’s dignity and not force anyone inside.

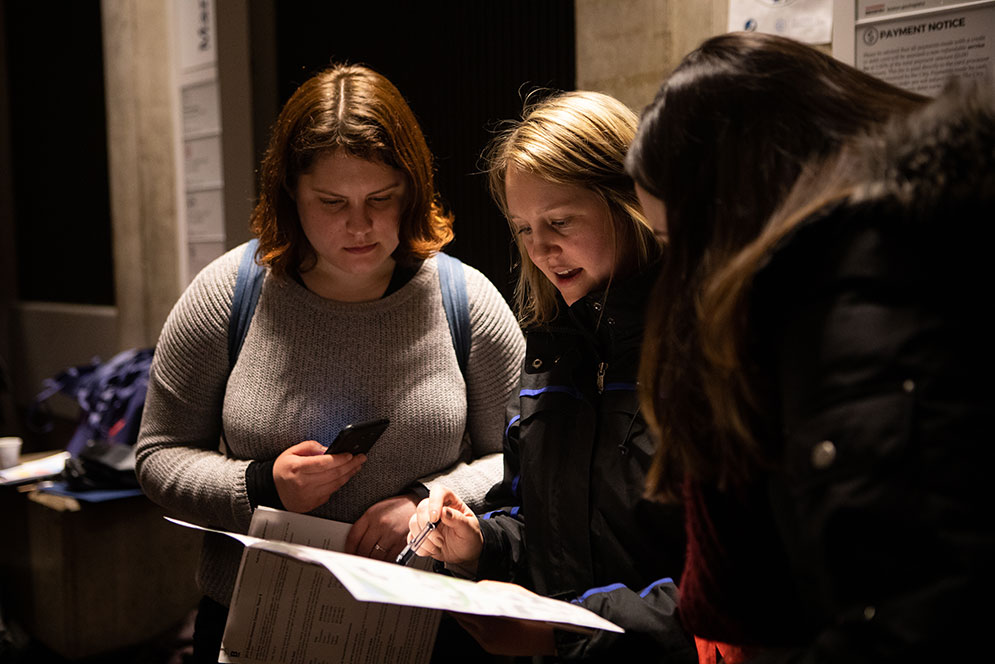

BU alum Kate King, deputy director of the city’s Intergovernmental Relations office (center), helps SPH student volunteers Danielle McPeak (left) and Meghan Smith map out their route to reach out to the homeless.

Out of the dark and cold, two more homeless souls appeared on the sidewalk near Bobby, a man and a woman, both of them ill-clad for the weather and looking exhausted and miserable. They immediately accepted the group’s offer of shelter. Heiger-Bernays called Jake Sullivan, BU’s vice president for government and community affairs, who has been volunteering with the homeless census for 17 years, to ask him to dispatch an outreach van. Along with the volunteers on foot, a fleet of vans was crisscrossing the city, responding to requests to take people to shelters. (The numbers from the census are still being processed.)

While the three of them stood in the cold, Bobby asked the woman if she had a light. Her boyfriend angrily told Bobby to back off, threatening to hurt him. Bobby threatened him back.

Remembering something they’d learned in their bystander intervention training—change the subject, if necessary—Wahbi and Bullard made Bobby an offer: if they bought him cigarettes and a lighter, would he go to a shelter? Yes, he would. Buying cigarettes for a homeless man may not have been ideal, but as Wahbi said later, this was a case of “harm reduction.”

“In this world when you don’t have anything, you still have your dignity and you’re going to fight to keep that dignity,” Wahbi said. “At the end of the day he seemed like a kind man who was just looking for a lighter and a smoke.”

Wahbi, who grew up in California after his family left Egypt and is experiencing his first Boston winter, stayed with Bobby while Bullard went off to buy cigarettes.

Heiger-Bernays and the two other students in their group, Andrea Dettorre and Mansi Varma, brought the couple to a bench inside a nearby bus shelter that offered minimal protection from the wind.

The man said he was a military veteran who had done three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and had PTSD. “Don’t worry about me,” he said. “I’ve been through a lot. I know how to handle myself. Take care of my girl.”

His girlfriend, who wore a flimsy jacket and carried a small cream-colored suitcase, barely spoke, except to thank Heiger-Bernays and the students. Her lips were turning blue. Varma and Dettorre pressed their packets of hand warmers on her. They covered her hands with theirs. Dettorre hadn’t had much experience with homeless people before volunteering for the census, and she had felt nervous at the beginning. But now she felt calm, and focused on helping the two stay warm until the van arrived.

Huddled together on the bench, the couple recited the Lord’s Prayer. Squatting on the ground in front of them, Dettorre joined in.

“Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven…”

SPH student Andrea Dettorre warms the hands of a homeless couple while they wait at a bus shelter near City Hall for a van to a shelter. “We all share this city,” Dettorre says.

Salvation arrives

Another group of volunteers came along carrying bags of blankets and clothing. They gave hats and gloves to the couple, who thanked them profusely.

Heiger-Bernays checked in with Sullivan. It was a hectic night on the streets of Boston, but the van was on its way. She worried aloud about the couple and Bobby—but also about Varma, who was shivering under her layers of clothing. Like Wahbi, Varma had grown up in California and had never experienced cold like this before. Hearing the forecast that morning, she had fleetingly considered dropping out. “I thought: am I willing to be inconvenienced?” she had said earlier in the evening. “Do I love the homeless? The answer is, yes, I love the homeless.” She has even befriended a number of homeless people she’s met on the streets of Boston.

Across the street, meanwhile, where Wahbi was waiting with Bobby—and keeping him from falling down—Bullard arrived with cigarettes and a lighter. Bullard and Wahbi lit a cigarette for Bobby and helped him slip on a pair of Wahbi’s gloves.

“I love you guys,” Bobby said. “Thank you for helping me.”

The two classmates answered together: “We love you, too, Bobby.”

Finally, after what seemed like an eternity on the frigid streets, but was actually only about 15 minutes, a van from the Pine Street Inn pulled up to the corner where Bullard and Wahbi were waiting with Bobby. Bobby got into the van. So did the couple, with help from Heiger-Bernays, Dettorre, and Varma. Wahbi warned the driver there was tension between the two homeless men.

“We love you, Bobby,” Wahbi and Bullard tell Bobby before he climbs in an outreach van to shelter.

The van pulled away into the night. Splitting into two groups, Heiger-Bernays and the students continued on their way toward TD Garden, looking for more people with nowhere to spend the night. They were mindful of what Jim Greene, the city’s point person on homelessness, had told them at City Hall earlier: “Think about where you’d go to get warm if you were outside tonight.” Walking through a dark parking lot, Bullard headed toward a giant dumpster. That’s where he would go, he said. The dumpster turned out to be chained shut.

Inside the North Station MBTA station, the group from SPH introduced themselves to two young men seated on the floor above the escalator on worn dirty blankets. “I can’t go to a shelter,” one of the men, who wore a Red Sox cap, told Bullard. “They make me too anxious.” Bullard said he understood.

At 11:45 pm, Heiger-Bernays thanked the students for what they’d done and for the compassion and respect they had showed Bobby, the couple, and the two young men on the floor at North Station and wished them a safe trip home. They all headed home on the subway.

Dettorre said the next day that throughout the night she had been thinking about what Walsh had said to the group: Every person you meet has a story. Every person you meet is loved by somebody. One night of volunteering was just one night, she said, but she was committed to doing more than a night of volunteering to make sure that everybody on the streets felt loved.

Martin Walsh, Boston mayor (center, Patriots cap), at City Hall with Medical Campus students and other BU volunteers before they head out to the street to count homeless people and offer them shelter.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.