MLB Umpires Missed 34,294 Ball-Strike Calls in 2018. Bring on Robo-umps?

After studying four million game pitches, BU researcher suggests how to fix a broken baseball system

The Red Sox’ Mookie Betts (right) is in disbelief as home plate umpire C. B. Bucknor (left) calls him out on strikes. Photo by Jim Davis/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

MLB Umpires Missed 34,294 Ball-Strike Calls in 2018. Bring on Robo-umps?

After studying four million game pitches, BU researcher suggests how to fix a broken baseball system

This article is based on 11 seasons of Major League Baseball data, over four million pitches culled and analyzed over two months by Boston University Master Lecturer Mark T. Williams and a team of graduate students at the Questrom School of Business experienced in data mining, analytics, and statistics.

Baseball is here, another season of amazing catches, overpowering pitching, tape-measure home runs, overpriced beers, and, yes, television replays of every missed call by umpires, revealed in painful, high-definition slow motion.

It’s time for Major League Baseball to put an end to the agony caused by at least some of those blown calls—the balls and strikes.

Each season, MLB home plate umpires make tens of thousands of incorrect calls (read on for evidence backing up that assertion). These controllable errors impact players, managers, batters, pitchers, performance statistics, game outcomes, and even the big business of fantasy baseball. They shorten careers and diminish fan experience. Pace of play is also impeded.

But throughout its history, MLB has protected its error-prone umpires, resisted adopting strong performance measurements, and not taken advantage of available technology that could better the game. At a time of autonomous cars and machine learning, MLB needs to embrace useful change.

The duty of an umpire is complex: get the split-second call right. It is a mentally and physically demanding job. For 2018, there were 89 MLB umpires, all of them with a profile of male, average age of 46, and 13 years of experience. Each season, umpires individually participate in an average of 112 games, one-fourth of them (28) from behind home plate, calling about 4,200 pitches. A crew of four umpires is assigned for each game, assuming one of four designated field positions (except for the World Series, when seven umps are used).

To minimize the chance of undue influence, these game assignments are not publicly announced until 10 to 20 minutes prior to each scheduled start. The home plate umpire exerts the most influence in the game, making judgment calls on any pitch that is not hit. Currently umpires carry out this important role without technical assistance.

This human element of the game adds color but it comes at a high cost: too many mistakes. In 2018, MLB umpires made 34,294 incorrect ball and strike calls for an average of 14 per game or 1.6 per inning. Many umpires well exceeded this number. Some of these flubbed calls were game changing.

YouTube is flooded with videos of bad umpires in action. Watching these uploads has turned into a sport itself. Titles such as worst ball, strike, and check-swing calls in baseball history to the biggest umpire blunders of all time have gained wide viewer attention. Blown calls only undermine the integrity of the game, slow down pace, hurt averages, and prevent the athletes from being able to maximize their potential performance.

Right after the 2018 All-Star break, the Colorado Rockies and Arizona Diamondbacks met at Chase Field for an important National League game. The Rockies were up 6-5 in the ninth, but Arizona, with two outs and two on base, was threatening a comeback. Wade Davis, the Rockies closer, got ahead with a 1-2 count on slugger Nick Ahmed. The next pitch, a 90-mph cutter thrown toward the right-handed batter’s box, landed significantly outside the strike zone. To the disbelief of Diamondback fans, umpire Paul Nauert called the stray ball a strike, ending the ballgame.

Yet when analyzing the data, this call should not have come as a total surprise given Nauert’s performance over the last 11 seasons, which landed him firmly on the Bottom 10 of MLB’s list of umpires (see chart). Moreover, MLB umpires have a pronounced biased, greatly increasing the odds, on a two-strike count, that a true ball will incorrectly be called a strike. In 2018, a total of 55 games were ended when umpires made incorrect calls.

Umpires are at the heart of baseball, every single pitched ball requires at least one, and sometimes multiple umpires to make some call. Yet, even though MLB has begun evaluating umpires with internal systems (such as Trackman), their performance statistics are not widely known, tracked, or readily shared. Fans can recite starting pitcher information but when it comes to who is umpiring behind home plate and their error rate, these relevant statistics are not public.

To take the debate beyond YouTube videos, anecdotes, and fan emotion, we applied a clinical approach in assessing MLB umpire performance. Our goal was to let data-driven evidence determine strong, weak, and rising-star performance. And to determine just how accurate umpires are in calling balls and strikes.

DATA DOESN’T LIE

For this research, we looked at game data from Baseball Savant, MLB.com, and Retrosheet. The time period chosen, the most recent 11 baseball regular seasons (2008–2018), presented over four million called pitches. Similar to players, MLB umpires were assigned numbers, so that games behind the plate could be easily tracked. All active umpires were included in this performance study, and their ability to accurately call balls and strikes was closely observed. All 30 major league parks are outfitted with triangulated tracking cameras that follow baseballs from the pitcher’s hand to across home plate. Ball location can be tracked up to 50 times during each pitch and accuracy is claimed to be within one inch. Statcast, an MLB subsidiary, is at the center of this system—the backbone of strike-zone graphics used during televised and live-streamed games. Called pitches and strike-zone overlay were populated from Baseball Savant, Pitch F/X (2008–16), and Statcast data (2017–18).

Experience level and age of each umpire were also compiled. Once the data was assembled, our team of researchers used available technology that compares the strike zone to the actual calls umpires made on each pitch, separating the correct from the incorrect calls.

After ball and strike accuracy performance was calculated by inning, game, month, and season, a bad call ratio (BCR) for each umpire was computed. This ratio was generated by dividing all incorrect calls by the total of judged pitches. The higher the BCR score, the more incorrect calls made. This rating process was repeated for each MLB umpire for each season. Once all umpire BCR scores were completed, groupings and trends emerged. Umpires were then rank ordered and separated into top, average, and bottom performers. Standard data mining, analytics, and statistical methods were applied, and performance ratios studied. The results that emerged from this study were troubling.

SUMMARY FINDINGS

This deep-dive analysis demonstrated that MLB umpires make certain incorrect calls at least 20 percent of the time, or one in every five calls. Research results revealed clear two-strike bias and pronounced strike-zone blind spots. Less-experienced younger umpires in their prime routinely outperformed veterans, and umpires selected in recent World Series were not the best performers. Results showed a declining but still unacceptably high BCR score, but on a positive note, only a marginal inter-inning call inconsistency. Findings also identified new and rising-star umpires and highlighted the pressing need to recruit higher performers.

Given how MLB is heavily dependent on performance statistics when evaluating players, it is surprising the league has been sluggish to apply similar rigor to umpire hiring, promotion, and retention.

The following five sections explore our summary findings in greater detail.

1

Two-strike bias—balls called strikes

Research results demonstrate that umpires in certain circumstances overwhelmingly favored the pitcher over the batter. For a batter with a two-strike count, umpires were twice as likely to call a true ball a strike (29 percent of the time) than when the count was lower (15 percent). These error rates have declined since 2008 (35.20 percent), but still are too high. During the 2018 season, this two-strike count error rate was 21.50 percent and repeated 2,107 times. The impact of constant miscalls include overinflated pitcher strikeout percentages and suppressed batting averages. Last season, umpires were three times more likely to incorrectly send a batter back to the dugout than to miss a ball-4 walk call (7 percent). Based on the 11 regular seasons worth of data analyzed, almost one-third of batters called out looking at third strikes had good reason to be angry.

Such game-changing biases give a new meaning to the need for batters to aggressively protect the plate. It also provides pitchers with added incentive to gain an early two-strike advantage.

Umpires’ biased judgment when a batter has a two-strike count:

2

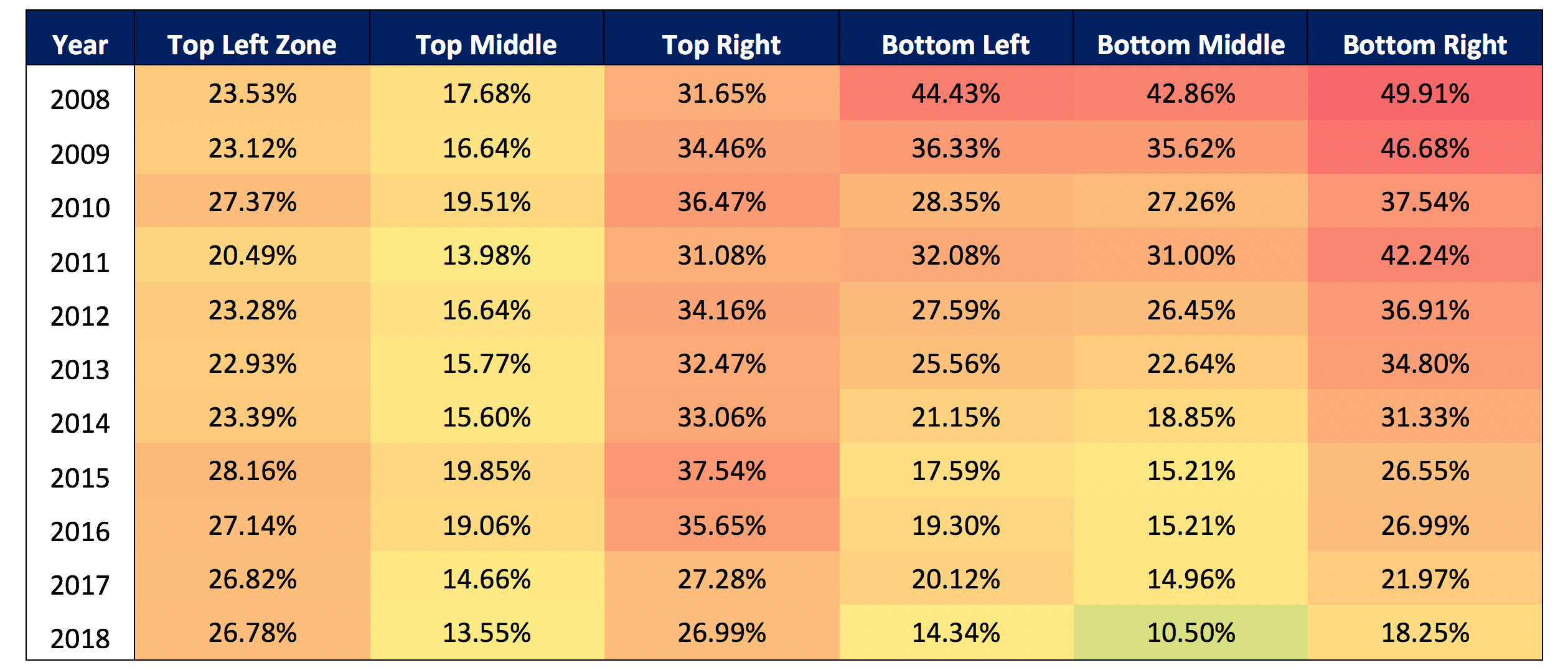

Strike-zone blind spots abound

Umpires from 2008 through 2018 also exhibited a pronounced and persistent blind spot with a number of incorrect calls at the top of the strike zone. Remarkably, pitches thrown in the top right and left part of the strike zone were called incorrectly 26.99 percent of the time on the right side to 26.78 percent on the left. And while there was marked improvement in umpiring, the incorrect calls around the bottom right strike zone in 2018 was still a mind-boggling 18.25 percent. Data results confirm that strike-zone blind spots penalized certain pitchers more than others. This time, however, batters benefited from such flubbed calls, as strike zones shrank, forcing pitchers to throw fewer pitches up in the zone. High strikes are typically harder to hit than low strikes for most batters.

Umpire blind spots—top part of the strike zone (right and left):

3

Less experienced and younger umpires outperformed veterans

Based on the research, professional umpires, similar to professional baseball players, have a standard peak. The study revealed that home plate umpires who made the Top 10 MLB performance list (2008–2018) had an average of 2.7 years of experience, and averaged 33 years of age, with a BCR of 8.94 percent. None of these top performers had more than five years of experience or were older than 37.

Nic Lentz, the youngest umpire to make this list, was 29. Logically this should not be a surprise finding given the physical demands and required reflexes needed to adequately perform this challenging job.

Taking into account standard peaking, MLB should consider moving away from the traditional four-person crew rotation, which gives every umpire time behind the plate, no matter how young or old, experienced or not, or how strong or weak a performer they are. A better system would assign the top performers to the most physically and mentally demanding field positions. At some point, prime is reached, and surpassed, and the body and statistics do not lie.

In contrast to the overall top performers, research uncovered that umpires on the Bottom 10 MLB performance list (2008–2018) had an average experience level of 20.6 years, were 56.1 years of age, and had an average BCR of 13.96 percent. This group’s error rate was a staggering 56 percent higher than the top 10 MLB performers. Umpire Jerry Layne, with 29 years on the job and at age 61, sported the highest BCR, 14.18 percent. This performance research clearly indicates that more experience and age do not necessarily produce the best umpires.

The counterargument to “younger is better” is that these umpires lack enough games under their belts to make many errors. However, there is another plausible reason why newer umpires tend to be stronger performers: they are more motivated to prove their worth. It also could be that they are beneficiaries of improved training and mentoring from older umpires. Regardless of the rationale, the data does not lie: younger MLB umpires are hitting the ball out of the park.

For the 2018 season, when compiling the Top 10 MLB umpires, only 2 on this all-star list had 10 or more years of experience. These exemplary umpires had an average of 6.3 years of experience, were 37.8 years of age, and enjoyed a BCR of only 7.78 percent.

The 2018 season performance also helps to illustrate the tight grouping of top performers (low BCR scores). Notice how the table is markedly sloped in favor of this younger and less experienced group. These umpires relative to the second clustered group appear to be in their prime.

For the 2018 season, the profile of those relegated to the Bottom 10 MLB list were entirely populated by veteran umpires with an average of 23.05 years of experience, who were 56.6 years of age, and earned a double-digit BCR of 10.88 percent. For the 2018 season, the Bottom 10 generated 40 percent more incorrect calls than the Top 10 MLB umpires.

Graphing performance results also highlighted a natural divide—umpires with at least 20 years of experience made more incorrect calls than those with 10 years or less of experience. Within peer groups, there were also strong pockets of poor performance. As highlighted in this 2018 bad call ratio (BCR) graph, the line delineates average umpire performance to experience relative to their peer group. Umpires above the line performed worse than others. The tight cluster of higher errors upon reaching 20 years on the job is also telling.

For 2018, Ted Barrett and Joe West were the top poor performers, making 495 and 512 incorrect home plate calls, for an average of 17.7 and 16.5 errors per game, respectively. Such bad call numbers can produce an array of new outcomes. For example, incorrect calls can extend pitch count and impact pitcher rotation and the reliance on relievers. As a starter gets deeper into his pitch count, one or two more balls can change game outcome. Bad calls in favor of batters can extend innings, and increase scoring opportunities.

Interestingly enough, Angel Hernandez, while far from having a breakout year, performed stronger in 2018 than his average over the last 11 seasons. Hernandez is routinely derided by MLB players as one of the worst umpires.

Our data also showcases the 2018 performance of new umpires such as John Libka, who at only 32 and with only 1.5 years of experience, had generated an impressive BCR of 7.59 percent. With that low BCR, he should win “Rookie Umpire of the Year Award.” On the more seasoned side, Mark Wegner should win “Veteran Umpire of the Year Award.” Both umpires are at the top of their game.

Anecdotally, veteran umpires such as Joe West (debuted 1978), have long earned the scorn of players and fans for their proclivity for bad calls. The statistics show that West made more incorrect calls than most. In fact, behind the plate, over the last 11 seasons he has averaged 21 incorrect calls a game, or 2.3 per inning. And while Angel Hernandez (debuted 1991) receives similar fan dislike, averaging 19 incorrect calls a game, or 2.2 per inning, even with this high error rate, compared to his peers, he performed better than others, escaping the 2018 Bottom 10 MLB list.

Season-by-season call variability is also a problem. Hernandez’s performance in 2017 was much worse than in 2018. In contrast, Joe West continued to produce a troubling amount of incorrect ball and strike calls.

Relying on gut feel and not armed with accessible and timely performance measurements, players and fans have little ability to objectively assess the league’s 89 umpires. Recently, Hernandez stated he only gets four calls wrong per game. His actual error rate, as evidenced in this research, was almost five times higher.

Unfortunately, while many fans are aware of the predilections of the poor performers, when it comes to the stellar 2017 season umpiring performances of Pat Hoberg and Eric Cooper or the 2018 season of John Libka and Mark Wegner, most fans are left in the dark.

And when it comes to the World Series, it’s official: the 2018 World Series umps were not the best.

After comparing the BCR performance of all umpires, the top performers were typically not the ones chosen for MLB’s most prestigious, most visible, and highly sought after assignment.

Of the seven umpires chosen for the 2018 World Series, no fewer than five exhibited a higher BCR than the overall league average. For the 2018 season, none of the MLB selected umpires were on the Top 10 performer list. However, Ted Barrett, a 2018 Bottom 10 performer, nonetheless got the top job as crew chief. In his two decades of umpiring, this was his fourth time selected to officiate the postseason finale. This decision by MLB was not a fluke. In 2017, two Bottom 10 list umpires, Paul Nauert and Dan Iassogna, were also picked. For the 2016 World Series, Joe West was selected to umpire again, the sixth time in his career.

In contrast, if MLB used a merit-based system, awarding the 2018 World Series assignment to the umpires with the lowest regular season BCR, a dream team of umps would have been fielded, one with much lower error rates and higher call consistency.

Umpires picked for the 2018 World Series also tended to be considerably older than the league average. Given the apparent inverse relationship between age and top performance identified previously, this is problematic.

MLB is simply ignoring valuable, available data.

Despite the hard evidence, each season, MLB continues to keep questionable performers, some past their prime, on the job. The past three World Series were only the most recent examples. Game by game, season by season, poor-performing umpires remain on the field. When the error rate can vary as much as 56 percent between the bottom and top performers, who is behind home plate matters a lot. In 2018, 2 percent of all major league games (55) were ended by incorrect calls, an increase of 41 percent from the previous year (39).

Given the importance of these games and of getting the calls correct, MLB must rethink the process it uses, including incorporating more performance-based measurements when determining hiring, retention, and assignments. If the league is truly committed to game improvement, its officials should aggressively recruit and retain high-performing umpires, as any smart industry does. Unfortunately, the way the current seniority system works, MLB typically has only one or two new umpiring slots open each season. Such a flawed system also prevents promising talent and rising stars from gaining proper recognition or access to best assignments.

Research results also point to the fact that umpire compensation is not closely aligned to performance. The World Umpires Association is the union that represents all MLB umpires. Those with seniority can earn salaries above $450,000 while rookies start at about $150,000. Umpires receive generous travel allowances, including flying first-class. There is also more pay for playoff games. Whether a game takes three to five hours to play, and regardless of whether 2 or 20 incorrect calls are made, umpires enjoy the same pay. The last labor contract was approved in January 2015 and expires at the end of 2019. Study findings support the need for MLB to make stronger performance-based measurements central to the upcoming contract renegotiation process. Longevity alone is hurting the game.

4

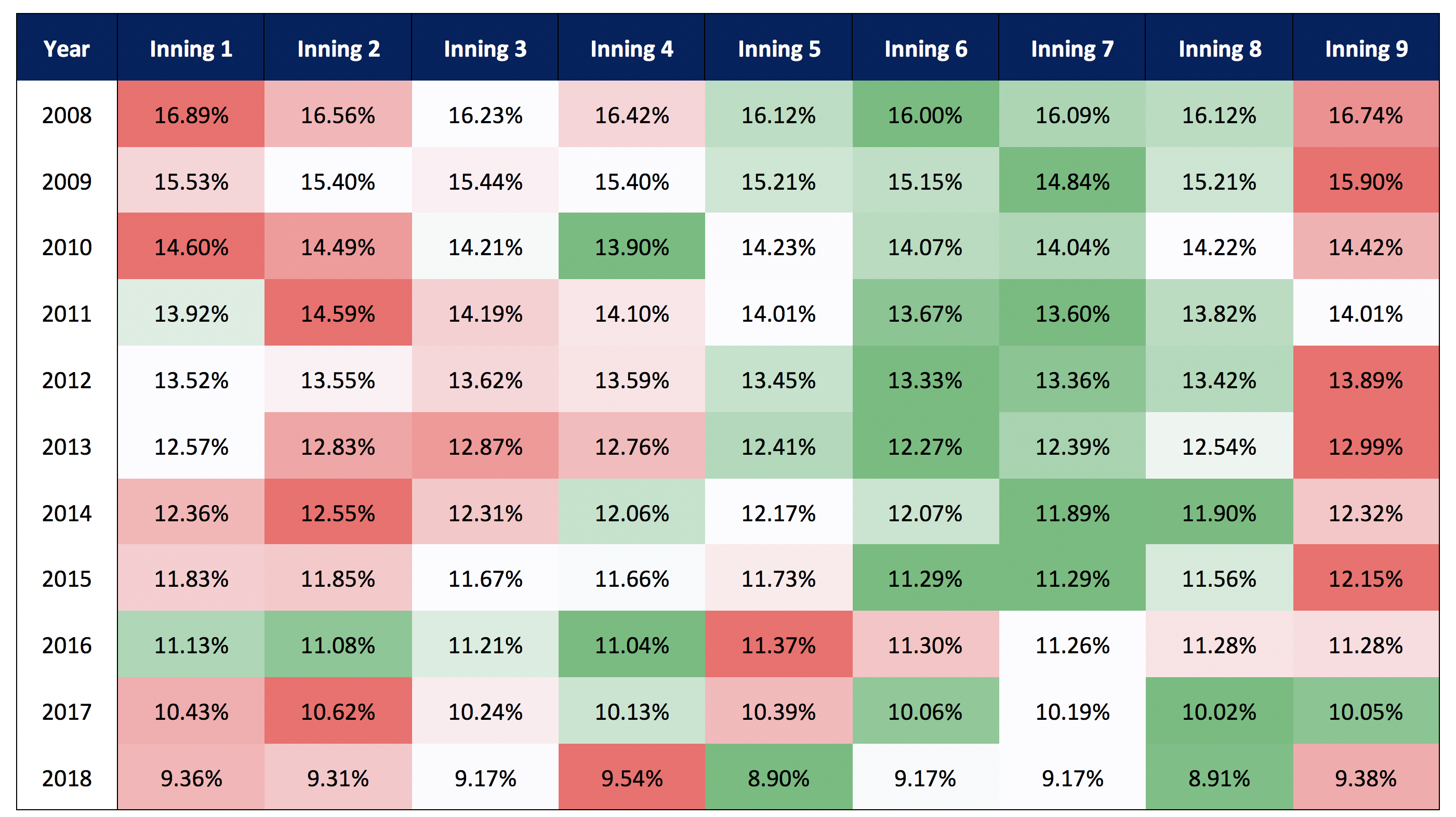

Umpire error rate inconsistency by innings was only marginal

Research results demonstrated that while there were high error rates on a per-game and season-wide basis, intra-inning inconsistency in calling balls and strikes remained only marginal. Data for the last 11 seasons showed a slight trend—higher error rates in early innings, less in middle innings, and slightly more by the critical ninth inning. When dissecting inning data on a per-ump basis, some exhibited even greater variability.

Umpires’ inconsistent performance by innings:

5

Bad call ratio by year

The error rate for MLB umpires over the last decade (2008–2018) averaged 12.78 percent. For certain strike counts and pitch locations, as discussed earlier, the error rate was much higher. Some years, the incorrect call ratio exceeded 15 percent. In 2018, it was at 9.21 percent. And while Major League Baseball might attempt to highlight this trend as a sign of strong umpiring, to the contrary, if there are ways to push error rates even lower—through better hiring practices and integrating useful technology—they should be adopted.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Technology

As this research has demonstrated, poor umpiring persists. Despite years of data-driven evidence, MLB has been slow to expand the ranks of younger umpires, missing the opportunity to rapidly lower unacceptably high bad call rates. The league has also dragged its feet in putting strike zone–assisted technology behind the plate. In a thinly veiled attempt to silence vocal critics, MLB recently announced it will begin to test robot umpires, but only on a small scale, through the unaffiliated Atlantic League farm program. Instead of addressing this pervasive big-league problem now, MLB continues to stall.

Innovations such as the radar gun, instant replay, pitch graphics, Doppler radar, and strike-zone evaluation systems have greatly improved baseball and fan experience. Yet umpires continue to call balls and strikes like they did 100 years ago when Babe Ruth reigned supreme and the Ford Model T ruled the roads. Technology does not have to mean the death of umpires. Rather it’s a tool to allow them to do a better job.

Adopting strike-zone technology would free up umpires to remain focused on other aspects of the game and make sure pace of play is maintained. Major League Baseball has been a follower and not a leader in adopting innovative technology. In contrast, other professional sports have increasingly relied on high-tech aids, rapid communication, and centralized control rooms to improve officiating. In European soccer, at the World Cup, and professional tennis, Hawk-Eye technology is the standard. In the National Football League, tech-assisted verification is increasingly the norm. It is also customary for football referees, coaches, and quarterbacks to be wired for real-time communication. In international cricket, umpires have also gained marked improvement through communicating calls via wireless technology.

Tech-assisted umpires

To dramatically improve behind-the-plate umpiring, the solution is not for baseball to bring in the robots and fire the umpires. Baseball has too many one-off situations and complexities to assume a bot could do everything ump-like. However, MLB has a unique opportunity to set a higher standard, apply performance measurements, and strengthen human-software collaboration. For this to move forward, the World Umpires Association would need to acknowledge existing umpiring deficiencies, accept stronger performance-based approaches, and support innovative tech solutions.

Umpires connected to central control could easily be fitted with headsets or earpieces, conveying real-time ball and strike information. These umpires could make calls correctly, quickly, and effortlessly. Time-honored and much-beloved behind-the-plate signs, signals, and sounds would not be disrupted. Umpires would remain in control, having override ability under certain circumstances, such as if a ball hit the ground before crossing the plate or if a system outage occurred.

Biases would be eliminated. Strike-zone subjectivity would be minimized, freeing up more of the plate for pitchers and allowing batters to focus more on hitting and less on guessing inconsistent strike zones. Pace of play would increase. It would also reduce the escalation of umpires blaming players and managers.

CONCLUSION

Major League Baseball’s goal should not be to resist change, but to adhere to the official strike zone that its own rules make clear—on every pitch. High-tech aids and greater recruitment of competent younger umpires is another important step. Imagine player and fan experience and what baseball would look like if each year the more than 34,000 incorrect calls vanished. Fans could focus more on umpire standouts and rising stars and applaud the veterans who are able to withstand the test of time, just like the best aging ballplayers are appreciated.

It is unrealistic to assume that home-plate umpires, unassisted, can collectively achieve the accuracy rates increasingly demanded by the sports industry and deserving fans. Given that umpires hit standard peaks, hiring and retention policies need to be adjusted accordingly. Adopting a stronger performance-based system coupled with readily available technology would allow the human aspect of the game to remain while respecting the benefits that can come with advancing technologies. At minimum, using a tech-assisted approach would produce results no worse than our existing band of MLB umpires.

Mark. T. Williams (Questrom’93) is the James E. Freeman Lecturer in Management at Boston University Questrom School of Business, where he teaches courses in financial technology and innovation. He can be reached at Williams@bu.edu. A lifelong baseball fan and author of several sports books, he would like to acknowledge the strong contributions made by Tianyang Yang, Brandon Cohen, and the rest of the Boston University student team, all of them master’s in science and mathematical finance students.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.