Body Worlds: Study or Spectacle?

Bioethics Society debates meaning of exhibition

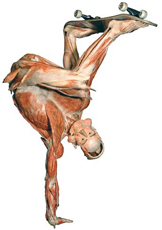

The latest exhibition at the Boston Museum of Science features skinless corpses posed as ballet dancers, archers, and hurdlers, slices of a brain, and a healthy lung and a smoker’s lung side by side. Displayed in German anatomist Gunther von Hagens’ Body Worlds 2: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies are real human cadavers and organs preserved with a technique called plastination.

The exhibition, which has both raised hackles and boosted museum attendance, is the topic of a BU Bioethics Society lecture on Thursday, December 7, at 6 p.m. in SED Room 130. The group will then visit the Museum of Science to see Body Worlds, which closes January 7.

“I find it educational because I know what I’m looking at,” says Jessica Gonynor, anatomy lab coordinator in the College of Arts and Sciences biology department. Gonynor will deliver the lecture, providing an overview of the exhibition and the issues it raises, among them, “How is it as education? As art? What are the political ramifications? How does it touch certain religious nerves?” she says.

The use of dead bodies for scientific purposes is not new, according to George Annas, Edward R. Utley Professor of Health Law, Bioethics, and Human Rights and chair of the School of Public Health’s department of health law, bioethics, and human rights. “We’ve always been able, in this country, at least for 40 years, to donate our bodies to science for dissection, research, and for transplant,” Annas says. “The big category is education — usually that meant [for med students]. That raises a question whether [Body Worlds] is a legitimate thing to donate your body to.” Is it educational, he asks, “or is it really an affront to human dignity?”

“I don’t necessarily have an answer to that,” the bioethicist continues, “but I don’t think you can give informed consent without seeing the exhibit, that’s for sure.”

Indeed, there is a voyeuristic aspect to the exhibition, Gonynor says. It has brought in unprecedented numbers of visitors to many museums, but has also engendered criticism from religious conservatives and some scientists. “Anatomists are worried that exhibitions of this kind will prevent people from donating their bodies to research,” she says.

The new James Bond movie, Casino Royale, hasn’t helped. A scene in the film takes place in a Body Worlds exhibition. “I don’t find it educational,” Gonynor says. “And I wonder what the royalties will go to. I would hope research and education.”

Both Gonynor and Annas, however, think that the exhibition does have educational value, although von Hagens, its creator, is at least as much a showman as a scientist. “I love the quotes,” Annas says of the enlarged quotes on display, from Jean-Paul Sartre, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, and von Hagens himself. “As if he’s in the same league with these guys!”

The bodies in von Hagens’ second Body Worlds apparently all come from consenting donors, according to what Annas says he learned from the Museum of Science. The source for the bodies in von Hagens’ first exhibition, in 1995, however, is murkier. “There’s no question,” Annas says, “that the early bodies were homeless people, unclaimed homeless people — there’s no consent from them.”

Bioethics Society faculty advisor Sir Hans Kornberg, a University professor and a CAS professor of biology, says the exhibition “seems to be a very genuine and sincere attempt to let people understand anatomy in three dimensions.”

“I’ve seen many carcasses myself,” Kornberg says. “I feel that once a person is dead, the identity of the person is gone, and it’s now just a collection of proteins and nucleic acids and membranes waiting to decay.”

Cosponsored by the Bioethics Society and the Student Activities Office, the lecture and trip are open to all students. Tickets to the exhibition are $16.

Patrick Kennedy can be reached at plk@bu.edu.