Thompson’s Spa: The Most Famous Lunch Counter in the World

By Peter Szende and Heather Rule

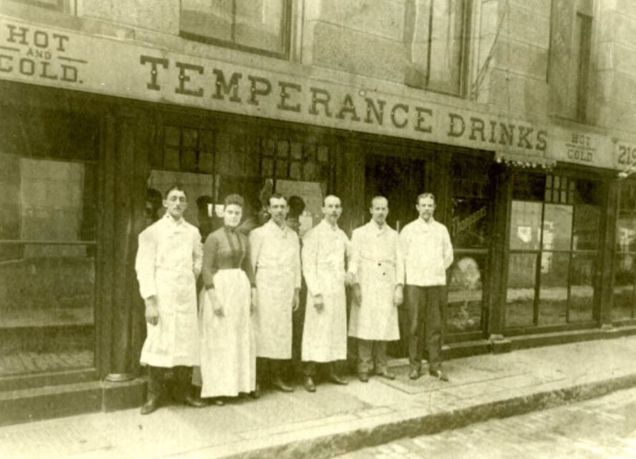

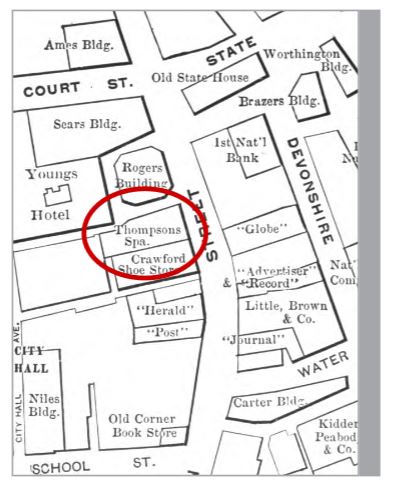

The legacy of Charles Eaton began with a little bit of luck. In 1882, while walking along Washington Street in downtown Boston, he passed a vacant building that seemed to be a good site for a new business serving non-alcoholic beverages. In short order, he emerged with the lease. As an ironic twist, his new ‘temperance saloon’ would be located on the former site of the first tavern in Boston, which had been licensed to Samuel Cole in 1633.

The naming of Thompson’s Spa was deliberate. Eaton wanted to avoid the obvious joke his last name might incur as a restaurant, so he decided to use his wife’s maiden name, Thompson. He also hoped to invoke the idea of the health restoring qualities of mineral water, which had been pioneered in the Belgian town of Spa and then popularized in American resorts such as Saratoga Springs, New York.

By 1895, there were more than 100,000 soda fountains in the nation, and the soft-drink empires of Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola were rapidly emerging. The Bulletin of Pharmacy declared soda “the great American drink.” Charles Eaton recognized this movement early and capitalized on it. His idea of a non-alcoholic bar was immediately successful and the company began to turn a profit after only six months. Although beverages eventually became a secondary product, they remained a significant part of the business, with soda drinks alone generating over $50,000 annually during the early years.

The business began to grow even more quickly after Eaton realized that his customers wanted food to go along with their beverages. He started to offer sandwiches, then added pies and cakes, and then expanded the menu significantly. The food soon became more legendary than the beverages, as Bostonians began to spread the word about its quality. Eventually, the restaurant would eclipse the soda fountain and be recognized by Baking Technology magazine as “the best eating house in the world.”

Popularity and Expansion

According to the American Magazine of Civics, Thompson’s Spa was “visited by all who desire a good soft drink or lunch.” It quickly became the preferred meeting place for businessmen, lawyers, doctors, judges, and politicians. Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Theodore Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland, and Woodrow Wilson were all guests at Thompson’s Spa. Nonetheless, “men of all classes” dined alongside these prominent men, making it a gathering place for all.

The fame of Thompson’s Spa was due in no small part to Eaton’s successful promotional strategies. He installed a giant thermometer on the exterior of the restaurant, which became the standard for temperature in Boston. It was reported daily in The Boston Globe with the tagline “The Temperature Yesterday, as indicated by the Thermometer at Thompson’s Spa.” Similarly, a clock on the exterior was the best known sidewalk timepiece in New England, adding yet another aspect of notoriety to Eaton’s original location.

Although today one might suspect that Charles Eaton had hired the best publicist in town, his son Malcolm claimed they “never spent a penny in advertising, yet at certain hours of the day the place is overcrowded.” Even without paying for publicity, the restaurant and its employees were phenomena of public interest, often generating newspaper coverage. The counter girls – considered to be some of the most eligible bachelorettes in Boston – and the male soda jerks often appeared in stories about their promotions, vacations, engagements, and even housewarming parties.

By 1916, the restaurant was serving between 10,000 and 12,000 customers daily. Expansion into multiple units became a necessity to meet the excess demand. This started with two satellite branches providing boxed takeout lunches in 1926. Another full-service location was added on Tremont Street in 1929. At the height of expansion, the Eatons had an empire consisting of ten different locations in the Boston area, serving more than 25,000 guests daily. Thompson’s Spa also sold branded chocolates in drug and candy stores throughout New England.

It even became a publicly traded company during the stock market frenzy of the late 1920s.

Management and Operations

The operations of Thompson’s Spa were the driving force behind its success. The back-of-house systems were extremely innovative and kept under the strictest secrecy. A visitor who inquired about these reported that he “only got the air,” which was the typical response to anyone trying to gather information.

Charles Eaton, who was a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, invented many of the machines used in his kitchens. These included electric order signal boards and pipes that brought coffee to the front-of-house. One observer speculated that these were “fed with live steam while in circulation” or that each coffee pipe was “incased in a hot water pipe.” Supposedly, no one ever succeeded in copying his designs, and the Eatons believed these innovations were crucial to the success of their restaurants.

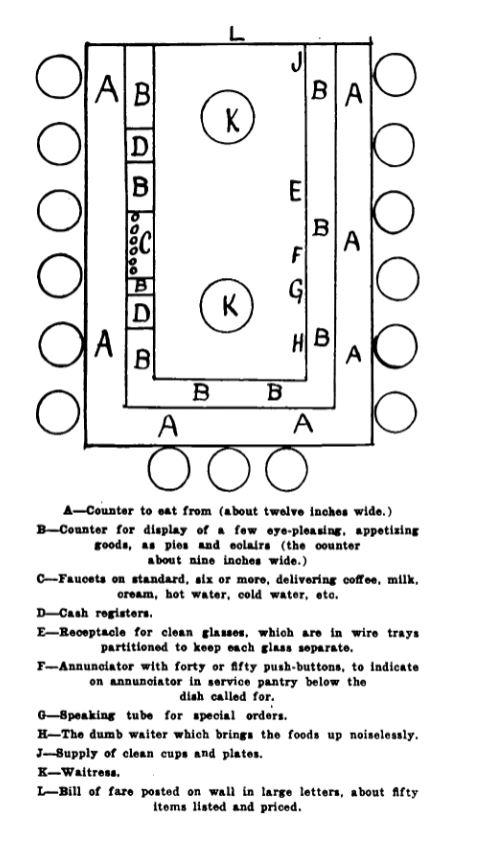

The service in the dining rooms was much more easily observable than the kitchen operations. The main location was comprised of numerous small rooms connected together, with capacity for up to 20 people each. Specific rooms were designated for cigars, soda fountains, candy counters and so forth. The dining rooms were focused around lunch counters, where unique service methods were employed. After each customer ordered, the server would press a button on an annunciator that communicated the details to the kitchen automatically, supplemented by a speaking tube for special orders. Almost immediately, the food would be received from the kitchen through a dumbwaiter system under the floor. No tipping was allowed.

The soda operation was also a point of pride for Thompson’s Spa. The men who worked at the counter were considered experts in their field, who according to a local journalist “would have looked more at home tending bar at the Ritz.” The original fountain was in place for 33 years and was considered to be one of the most famous soda machines in Boston, if not the entire country. The system stored syrup on the third floor of the building and was connected to the fountain through cooled pipes. In 1915, the entire setup was replaced with even more advanced equipment, which also enabled the countermen to face the customers at all times during the process.

One reason people kept returning to Thompson’s Spa was its sense of public service. In one memorable moment, Charles Eaton gave a young paperboy outside the restaurant a new outfit for Christmas.

In another instance, a man who had ordered a box of chocolates discovered that he had forgotten his money, but the clerk offered to let the man take the box on trust. Many guests became friends with the employees, who even received postcards from traveling customers.

Thompson’s Spa encouraged its employees to think like owners. Foreshadowing the motto of the modern Ritz-Carlton company, the American Magazine of Civics suggested that “all the employees are well paid and treated as gentlemen and ladies.” Some were even sent at company expense to recover from illnesses in Bermuda. This philosophy created an extreme sense of loyalty in the employees, many of whom were employed by the Eatons for more than 30 years.

Decline

Thompson’s Spa entered a period of change after Charles Eaton’s death in 1917. A probate battle overshadowed operations and resulted in proposals to sell the company after it became clear the family could no longer work together. The firm survived this period of instability, but slowly began to lose its prominence in the Boston restaurant industry.

Another moment of distress occurred in 1940. Almost half of the employees of the remaining units, who had been treated like family members by Charles Eaton, went on strike. This did not stop service at the restaurants, due to the loyalty of the remaining workers, but it signified the beginning of the end for Thompson’s Spa.

The company changed hands in 1946, when the Sheraton Corporation bought a controlling interest for one million dollars. However, the operation of Thompson’s Spa soon turned into one of the biggest challenges the hotel company had ever faced. To fix the problem, Sheraton brought in the Exchange Buffet Corporation to manage the restaurants on a fee basis, with the right to purchase. Exchange Buffet later acquired Thompson’s Spa in 1949 and began planning improvements to maintain its famous traditions in a modern setting.

By 1958, however, the company was beginning to collapse. The original unit on Washington Street closed, with 150 employees laid off, and other locations soon followed. An advertisement for a renovated lunchroom at one location appeared a decade later, but the company finally disappeared completely from the Boston restaurant scene in 1968. At the site of its Tremont Street location, construction soon began on the first McDonald’s unit in downtown Boston, representing not only the demise of Thompson’s Spa, but also the end of the soda fountain era.

Conclusion

The memory of Thompson’s Spa continued for another generation. Eben Reynolds, who managed the company for the Exchange Buffet Corporation, taught a food accounting course at Boston University in the late 1940s. John Stokes, a former president and treasurer of Thompson’s Spa, similarly taught a course in food service management in 1969. Both courses included discussion of the restaurant’s innovative operations systems.

In 1983, a group of entrepreneurs hoped to resurrect the brand at the Temple Place location, and submitted a proposal to the Boston Redevelopment Authority. They intended to match the original quality of the “hearty soups, ample sandwiches, light hot-dishes and of course, the Spa’s famous pies and pastries.” The proposal did not win the bid, and the brand evaporated.

Thompson’s Spa was one of the most celebrated companies during an era in hospitality history that has now been forgotten. Soda fountains and lunch counters have been replaced with vending machines and fast food restaurants. Nonetheless, the legacy of Charles Eaton should not be overlooked. He had a groundbreaking idea, which became one of the most famous restaurant companies in the world. His innovative operational systems and mechanical inventions undoubtedly influenced numerous successors.

About the Research: Sources for this article included reports from newspapers such as The Boston Daily Globe and The Boston Globe (1888-1969), articles from popular magazines such as the American Magazine of Civics (1895) and Time (1946), articles from industry journals such as the Bulletin of Pharmacy (1895), the Hotel Monthly (1920), and Baking Technology (1923), documents within the archives of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, and a variety of secondary publications.

Peter Szende is Associate Professor of the Practice of Food & Beverage Management in the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. He has over 25 years of hospitality management experience in Europe and North America with organizations including Four Seasons Hotels. He holds a doctorate in business administration from the University of Economic Sciences in Budapest, Hungary and a diploma in hotel administration from the Centre International de Glion, Switzerland. Email pszende@bu.edu

Peter Szende is Associate Professor of the Practice of Food & Beverage Management in the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. He has over 25 years of hospitality management experience in Europe and North America with organizations including Four Seasons Hotels. He holds a doctorate in business administration from the University of Economic Sciences in Budapest, Hungary and a diploma in hotel administration from the Centre International de Glion, Switzerland. Email pszende@bu.edu