Federal Minimum Wage Debate: Are Gubernatorial Politics Behind a Hotel Line Employee Wage?

By Nicholas Thomas PhD. and Eric Brown PhD.

As the United States approaches mid-2016, seats throughout the Executive, Judicial, and Legislative branches of the federal government are in play. As Republicans and Democrats fight for control, the docket of debatable topics continues to grow. One issue in particular, employee compensation, continues to be one of the most popular in both state and federal level politics. While the federal-level discussion of minimum wage is increasing due to an Executive Order signed by President Obama to shift the minimum wage of Federal contractors and subcontractors to $10.10 (The White House, 2014), and a recent change in the federal overtime regulations, income inequality remains at the forefront of discussions at the state level.

According to two members of the Economic Policy Institute (Cooper & Hall, 2013), the average wage of a U.S. worker has declined over the past several decades. This decrease in wage, particularly for those in low-wage positions such as those found in the hospitality lodging industry, has caused a widening of income inequality among citizens of this country. In addition, while the erosion in wages is occurring, the distance (gap) between minimum wage workers and average United States hourly workers has increased to a ratio of almost three to one. In other words, for every dollar the average American wage earner makes, a minimum wage worker receives $0.37. For a historical perspective, the ratio was approximately two to one ($0.50) in the 1960s. This income inequality negatively affects the individual worker, the national economy, and industries like hospitality that have a high percentage of low-wage workers (Cooper & Hall, 2013).

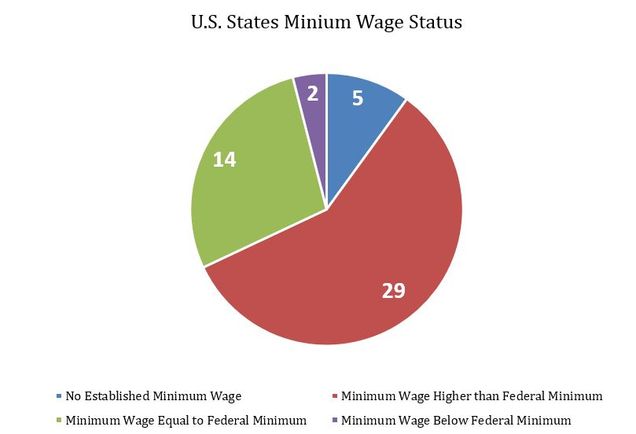

In January 2016, five states in the U.S. had no established minimum wage, 29 states had a minimum wage higher than the federal minimum wage, 14 states are equal to the federal minimum wage, and 2 states had minimum wages below the federal minimum wage (Wage and Hour Division, 2016).

As the top political official at the state level, the governor of each state has influence on the labor law of that state. Given the two primary political parties, different forms of support for labor legislation, and each state governor belonging to a political party, we hypothesized that states with democratic governors will have higher average wages in 1997 and 2015. Whereas states with republican governors will have lower average wages during those years. While the governor is not the only elected official that influences state-level changes in compensation mandates, they are the most visible figure and have the potential to spearhead legislative changes. Additionally, in their role as governor, they have the ability to veto new legislation as well as proposed amendments that come from the state legislature.

This study aims to examine the inequality in more depth by focusing on the average wages of two common lodging industry positions throughout the United States. The researchers want to establish if relationships exist between these lodging industry employees’ wages and the state governors’ political party affiliations and the cost of living in that state. In addition, the researchers aim to examine the federal minimum wage versus the average wages of these lodging positions.

Hospitality Wages: Are they affected by state governors?

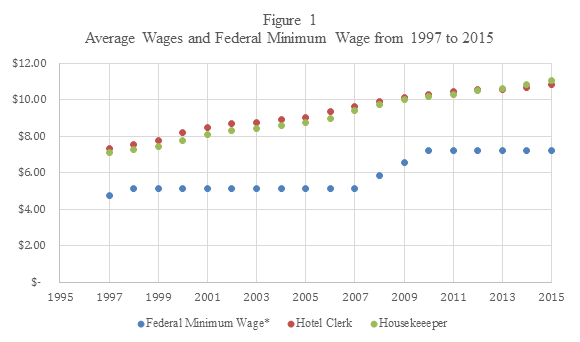

In 2015, the average annual wage for a hotel, motel, or resort desk clerk (“hotel clerk”) was $22,610 and a maid or housekeeping cleaner (“housekeeper”) was $22,990 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). With many employees working at, or slightly above, the minimum wage, employees could potentially benefit from an increase in the federal and state minimum wage values. From 1997 to 2012, the average wage of housekeepers nationwide had been slightly below hotel clerks. However, since 2013 the housekeeper position has a slightly higher wage ($0.06 per hour in 2013, $0.15 per hour in 2014, and $0.15 per hour in 2015).

ABOUT THE RESEARCH METHOD & DATA:

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is the primary federal agency in charge of measuring labor market activity. For purposes of this research, the researchers used the Occupational Employment Statistics collected by the BLS. At the time of analysis, data were available on a state-by-state basis from 1997 to 2015. The researchers developed a list of all gubernatorial party affiliations, average wages of hotel, motel, and resort desk clerks, as well as average wages of maids and housekeeping cleaners for every state in 1997 and 2015. The researchers then compared the wages of each occupation by using a t-test to determine if there was a significantly different mean for each group. The researchers used regression analysis to examine data in 2014. In the regression analysis, the researchers included political party, cost of living, and percent of employees covered by a union in each state.

In 1997, there were 17 states with a democratic governor, 32 states with a republican governor, and 1 state with an independent governor. Despite many states under a governor from a different party than in 1997, there were still 17 states with a democratic governor, 32 states with a republican governor, and 1 state with an independent governor in 2015. The researchers did not use Maine in 1997 or Alaska in 2015 because the states had an independent governor.

|

Table 1: One-tailed t-test of Differences in Mean Between States with a Republican Governor and a Democratic Governor (n = 49-50*) |

||||||

|

Mean (SD) |

||||||

| Republican | Democrat | t | p | |||

| Hotel Clerk 1997 | $7.02 (0.68) | $7.58 (1.31) | 1.98 | .027 | ||

| Hotel Clerk 2015 | $10.33 (1.28) | $11.61 (2.08) | 2.67 | .005 | ||

| Housekeeper 1997 | $6.91 (0.81) | $7.34 (1.03) | 1.82 | .037 | ||

| Housekeeper 2015 | $10.18 (1.23) | $11.70 (1.89) | 3.41 | .001 | ||

| *Maine excluded in 1997 and Alaska excluded in 2015 due to having an independent governor. | ||||||

For hotel clerks, the t-test was significant in both 1997 and 2015. This significance indicates the average wage for hotel clerks in states with a democratic governor in both years was significantly higher than the average wage of hotel clerks in states with a republican governor. On average, a hotel clerk would make an additional $0.56 per hour in 1997 and $1.28 per hour in 2015 if they worked in a state with a democratic governor. For housekeepers, the t-test was also significant in both years. Again, this indicates the employees made more, on average, when they worked in a state with a democratic governor. On average, a housekeeper made an additional $0.43 per hour in 1997 and $1.52 per hour in 2015 if they worked in a state with a democratic governor.

Considering Cost of Living, Unions, and Federal Minimum Wage

The differences between states with a republican and a democratic governor were significant; however, the findings are not definitive. A regression analysis including the political party of the governor and the cost of living index (COLI) for the state resulted in a significant regression model for hotel desk clerks in 2015 (F(2,46) = 4.45, p = .017). The political affiliation of the governor remained significant (t = 2.44, p = .019), but the COLI was insignificant (t = -1.28, p = .206). The outcome was similar for housekeepers (F(2,46) = 7.76, p < .001), with political affiliation of governor being significant (t = 3.13, p = .03) and the COLI being insignificant (t = -1.82, p = .075).

The political affiliation of a governor alone may not be a good predictor of the average wage of hotel clerks or housekeepers. However, there is a clear difference when examining the differences in wages post-hoc, making the political party of a governor worthwhile in discussion. In particular, when examining the political affiliations from 1997 to 2015, the average wages of employees in states with democratic governors are typically higher, but at the same time they also tend to have a higher COLI.

Federal Minimum Wage Influence in the Lodging Industry

In order to examine how the federal minimum wage influences changes in average wages, the researchers compiled a list of nationwide average wages from 1997 to 2015 of hotel clerks and housekeepers. In addition, the federal minimum wage in May of each year was included as the average wages form the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics comes from May numbers.

The federal minimum wage increased after May in 1997, 2007, 2008, and 2009. Each of the increases does not appear to have a direct impact on the average wages of hotel clerks or housekeepers nationwide. Figure 1 includes a graph showing a steady increase in the average wage of both positions. In years where there was an increase in federal minimum wage, the average wages of both positions appeared unaffected. In addition, the disparity between the average wage of all office and administrative support positions, the overarching category the Department of Labor places both positions in, seems to be growing over time. In other words, wages of these two lodging positions are growing at a slower rate than similar positions.

Figure 2 includes the difference between federal minimum wage and those of housekeepers and hotel clerks. It appears that the federal minimum wage influence decreases the gap between minimum wage and the average wage while the average wage continues increasing seemingly unaffected.

Theoretical underpinnings used to illustrate politics in research commonly stem from non-political areas, such as economics (Shavell, 1979; Besley & Case, 2003; Downs, 1957). For example, researchers commonly cite the Principal Agent theory as having applicability to not just economics, but also politics (Miller, 2005). Applied to this research, a state’s governor is acting as an agent on behalf of their constituents (the principal). This idea is somewhat counter-intuitive because an agent, traditionally, works for a principal, yet the governor of a state has significant influence and power over his/her constituency. This relationship presents a challenge because the agent is motivated to act in his or her own best interests to ensure eventual reelection.

A cursory review of Democratic and Republican Parties in the U.S. shows the Democratic Party has a stronger tendency to support workers’ rights compared to the Republican Party. In addition, each party’s platform supports this observation (Democrats, 2012; GOP, 2012). Although both parties show their support for the workforce, the policies they support vary significantly. The Republican Party traditionally focuses more on the development of the economy and the industries that support the restoration of lost jobs (GOP, 2012). The Democratic Party, besides discussing the economy, expressed their point of view by taking a side that favors the rights of workers and not management/ownership (Democrats, 2012). Wilhite and Theilmann (1987) examined the influence of political action committees on legislation and found that democratic members tended to support labor legislation and received more funding from labor unions.

The focus on labor has been a winning key for the Democratic Party in elections, with support from a large number of Americans with income less than $15,000. Fay (n.d.) found the Democratic Party had stronger support from individuals with income of $50,000 or less, and the Republican Party had strong support from individuals with income higher than $50,000.

While the hospitality industry includes a variety of sectors, one sector in particular, the lodging industry is the focus of this research. The lodging industry is continuing to rebound after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and common metrics of success are continuing to spur optimism throughout the United States market. Both academic and trade publications are highlighting the fact that operational managers are still concerned about one very critical challenge that continues to plague the industry – effective strategies to manage employees, and more specifically, strategies related to the hourly compensation rates for non-tipped lodging industry employees.

The academic study of politicians at the state the federal level is not a new trend, although the connection to the hospitality industry, and more specifically those issues related to compensation, is limited at best. While the merging of hospitality and political science is an infrequently made connection in the academy, unlike economics and political science, it can be a useful partnership for hospitality industry and academic practitioners. Although some research (Erikson, Wright, McIver, 1989) has shown that an elected state legislature is not good predictor of a state’s public policy, no empirical research exists looking at this fact in hospitality wages.

Research (Ghiselli, La Lopa, & Bai, 2001) has shown that in the hospitality industry, the salary and benefits package is one of the most prevalent reasons employees leave an organization. In previous work, Pizam and Ellis (1999) found a company’s approach to compensating (in terms of monetary and non-monetary benefits) their employees has an impact on turnover intention.

A common theory is that as minimum wage increases, low paid workers tend to see an increase in wages. However, previous researchers have shown it may not affect average wage, but instead decrease the wage inequality for the lower end of the wage distribution (Machin, Manning, & Rahman, 2013) or compress the possible starting wages (Katz & Krueger, 1992). WageWatch, Inc. addressed these issues in their executive summary as well. WageWatch, Inc. indicated an increase in starting wages would cause supervisors to make the same or slightly more than the employees they supervise, which would lead to a need for increased wages of supervisors (WageWatch Inc, 2014).

Pay Differences Between States

There are several reasons why difference in pay based on state may exist, although further research is warranted to provide a more comprehensive analysis of how these differences may affect the overall results. For example, there are dramatic differences in cultures, right to work legislation, cost of living, and dominant industries based in states or regions. In addition, state legislators are the ones who typically present, debate, and vote on new laws that could directly or indirectly influence wages in each state. Each of these on their own, or a combination of multiple dimensions, could be impact this results.

This research conducted an analysis on the average hourly wage of two common lodging industry positions; hotel, motel, and resort desk clerks, as well as maids and housekeeping cleaners. The results highlight that, on average, the hourly wage for these positions, in 1997 and 2015, were higher in states with a democratic governor when compared to states with a republican governor. While the debate on minimum wage’s impact on the wages of non-minimum wage workers is ongoing, this research indicates federal minimum wage increases have little influence on the increases in average wages of these two positions. There are implications of this analysis for hospitality industry practitioners, labor union representatives who are involved in the collective bargaining process, and members of the academy who are responsible for creation or teaching of policy related to compensation, benefits, and overall strategic human resources management.

Nicholas J. Thomas, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Center for Hospitality Research and Education in the School of Hospitality Leadership located within DePaul University’s Driehaus College of Business in Chicago, Illinois. He teaches undergraduate and graduate level courses related to customer service, human resources, and technology in the hospitality industry. He has frequently conducted industry-focused workshops throughout the United States and Asia. Prior to joining higher education, Dr. Thomas occupied leadership positions in some of the world’s most successful luxury hospitality organizations, with the majority of his career focused on human resources and lodging operations.

Nicholas J. Thomas, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Center for Hospitality Research and Education in the School of Hospitality Leadership located within DePaul University’s Driehaus College of Business in Chicago, Illinois. He teaches undergraduate and graduate level courses related to customer service, human resources, and technology in the hospitality industry. He has frequently conducted industry-focused workshops throughout the United States and Asia. Prior to joining higher education, Dr. Thomas occupied leadership positions in some of the world’s most successful luxury hospitality organizations, with the majority of his career focused on human resources and lodging operations.

Eric A. Brown, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Apparel, Events, and Hospitality Management department at Iowa State University. He holds a B.B.A. from the University of Iowa in Management & Organization, a M.S. in Food Service & Lodging from Iowa State University, and a Ph.D. in Hospitality Management from Iowa State University. Prior to entering academia, Dr. Brown held various positions in the lodging industry. At Iowa State University, he teaches and researches in the areas of leadership, management, and human resources.

Eric A. Brown, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Apparel, Events, and Hospitality Management department at Iowa State University. He holds a B.B.A. from the University of Iowa in Management & Organization, a M.S. in Food Service & Lodging from Iowa State University, and a Ph.D. in Hospitality Management from Iowa State University. Prior to entering academia, Dr. Brown held various positions in the lodging industry. At Iowa State University, he teaches and researches in the areas of leadership, management, and human resources.

PDF Version: Federal Minimum Wage Debate: Are Gubernatorial Politics Behind a Hotel Line Employee Wage?

References

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2003). Political institutions and policy choices: evidence from the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(1), 7-73.

Cooper, D., & Hall, D. (2013). Raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 would give working families, and the overall economy, a much-needed boost. Economic Policy Institute, March, 2013.

Democrats (2012). 2012 Democratic national platform: Moving America forward. Retrieved from http://www.democrats.org/democratic-national-platform

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. The Journal of Political Economy, 135-150.

Erikson, R. S., Wright Jr, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (1989). Political parties, public opinion, and state policy in the United States. The American Political Science Review, 729-750.

Fay, B. (n.d.). Economic demographics of democrats. America’s Debt Help Organization. Retrieved from http://www.debt.org/faqs/americans-in-debt/economic-demographics-democrats/

Fowler, L. L. (1982). How interest groups select issues for rating voting records of members of the U.S. Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 7, 401-413

Ghiselli, R., La Lopa, J., & Bai, B. (2001). Job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intent of food service managers. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(2), 28-37.

GOP (2012). 2012 Republican platform: We believe in America. Retrieved from http://www.gop.com/2012-republican-platform_home/

Katz, L.F., & Krueger, A.B. (1992). The effect of the minimum wage on the fast food industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 46(1), 6-21.

Machin, S., Manning, A., & Rahman, L. (2003). Where the minimum wage bites hard: Introduction of minimum wage to a low wage sector. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(1), 154-180.

Miller, G. J. (2005). The political evolution of principal-agent models. Annual Review of Political Science, 8, 203-225.

Pizam, A., & Ellis, T. (1999). Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 11(7), 1-18.

Shavell, S. (1979). Risk sharing and incentives in the principal and agent relationship. Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 55-73.

The White House (2014). Executive Order — Minimum Wage for Contractors. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/02/12/executive-order-minimum-wage-contractors

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). May 2015 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm

Wage and Hour Division (2016). Minimum wage laws in the states – January 1, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/america.htm

WageWatch Inc. (2014). Executive summary. Presented at the AH&LA Board of Directors Meeting and Special Meeting of Members, Washington, DC, March 2014. Retrieved from www.ahla.com/uploadedFiles/BoardBookMarch2014.pdf

Wilhite, A., & Theilmann, J. (1987). Labor PAC contributions and labor legislation: A simultaneous logit approach. Public Choice, 53(3), 267-276.

3 comments

Good evening, everyone! I’ve always dreamed of becoming a blogger and I think there are people here who dream about it too. I have realized my dream and I want to help you. https://easytube.pro/ has become my best friend in the vlogging world. It helps me create engaging content, edit videos like a pro, and provide my audience with unforgettable emotions. As a blogger, I can’t imagine my work without this tool!

Living at Aazie Pg Kota has been an absolute pleasure! The facilities are top-notch, the staff is friendly and accommodating, and the location near Allen Coaching is incredibly convenient. Highly recommend for anyone looking for a comfortable and secure living space in Kota.

Hey there! Ready to dive into the excitement of IPL betting? Log in to zotabet and get started!