Evolution or Extinction? Leadership through Innovation in a Time of Crisis

By Dr. Taylor Peyton

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has been accelerated by congregation and travel. By “congregation,” I mean humans gathering to interact in shared, physical space, and, by “travel” I mean that customers traditionally go to a hospitality business to receive their desired service. Our industry has historically depended on both congregation and travel in its service offerings.

Due to COVID-19, the hospitality business context has changed rapidly and dramatically, and we are already seeing early adaptations that range from downsizing, to mitigation, to capitalization. For example: both restaurants and hotels have cut costs by reducing operations and laying off workers; some hotels are offering reduced room rates to re-incentivize travel; and many restaurants have increased takeout services given the risks of congregation.

How can leaders leverage what the hospitality industry values and already does extremely well, so they can creatively apply those beliefs and skills to this chaotic, unfolding situation? Which deeply held assumptions might be worth questioning to maximize hospitality organizations’ ability to adapt to changing times?

This article invites hospitality leaders to explore a reflective method of problem-solving, inspired by the Immunity to Change method (Kegan & Lahey, 2001), which is a structured self-inquiry process useful for adaptive work.

To best serve hospitality leaders in this shifting context, I suggest that they walk through the following steps to generate new ideas:

- Descriptively define the context (i.e., the situation, or the qualities of the specific problem at hand)

- Identify a core value held by their organization

- Think about what easy solutions exist that align with that core value

- When there are not easy solutions, reflect on what underlying assumptions their business holds about that core value (relative to how business is done)

- Imagine shifting the underlying assumptions in Step 4, to innovate practical solutions

To demonstrate this process, I have set-up Step 1 as a hypothetical in the next paragraph, and then I provide an example table that lays out Steps 2-5 so this process can be workable. By doing this, I hope this article may invite hospitality leaders to think differently about the times ahead, and what related upcoming challenges mean for their businesses. And away we go . . .

As a thought experiment, let’s assume the worst for the hospitality industry, and imagine a new context (perhaps the version of a world affected by the COVID-19 pandemic for several months) that presents the following two trends that may sustain in direct response to our inability to congregate and travel: social distancing and staying local. Assume for a moment that people remain mostly home-bound for their work and life activities, and that they start to live off their own land, to build small tribes with their neighbors, and to self-organize into networks of neighborhoods. Let’s examine the problem from the perspective of restaurant owners, who will now need to learn to thrive in the new context where their customers are now social distancing and staying local. Consider: What might operating a restaurant look like under these conditions?

As you let your imagination roam, you’ll see that a restaurant offering an in-person dining experience that now must operate within a context of social distancing and staying local is what leadership scholar and practitioner Ronald Heifetz would call a highly adaptive problem, which is the kind of problem that can only be solved by shifting assumptions and applying new learning (Heifetz, 1994). Adaptive problems are different from technical problems, which can be solved with existing knowledge and easy fixes (Heifetz, 1994). Restaurants that have recently shifted their business to provide high volumes of takeout food have found a technical solution to these changing times, so we will analyze that business decision in the table below.

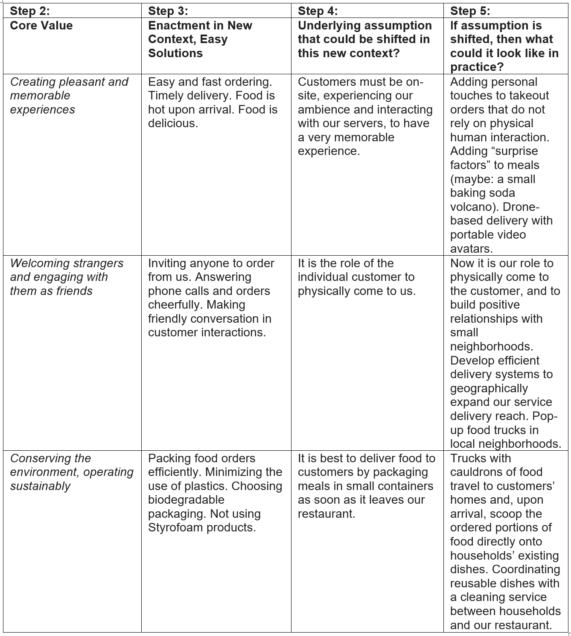

Read the table from left to right. Start with the core hospitality value in the first column (Step 2), then look to its enactment in the new context in the second column (Step 3). Much of that is technical, and we are already seeing it from some restaurants. Then move to the third column (Step 4), which generates an assumption underlying that core value we started with in the first column. Perhaps there are multiple assumptions underlying a core value; that is possible and likely. Finally, the fourth column (Step 5) creatively answers the question: if the underlying assumption(s) were shifted, what could the enactment of the core value then look like in practice?

TABLE: Example for a Restaurant Shifting its Business to Food Takeout Service:

I encourage you to use this method in your own way, to support the reflective processing you are already applying to the segment of the hospitality industry you work within. Fair warning: if you do this exercise correctly and deeply, the ideas in the far-right column in your table will be “out there,” and that is the objective.

Overall, hospitality will not need to change its core values that define it as an industry. Rather, it will need to re-envision how enacting its core values will happen in this changing context. This kind of visioning work is much more challenging when it calls for shifting assumptions underlying core values, but that is the seed of true innovation.

Dr. Taylor Peyton is an Assistant Professor at Boston University’s School of Hospitality Administration, where she teaches leadership and human resources. She is also principal of Valencore, a leadership development firm that specializes in soft skills training for executives of various industries. Taylor has published peer-reviewed articles and has authored over 40 research studies, presenting findings to academic conferences and to general audiences. Her research interests include employee authenticity and emotions, organizational leadership, passion for work, and power use in organizations. She studies employees’ psychological experiences — or inner life — at work, specifically with regard to their emotional regulation and experiences of authenticity as they interact with their customers, colleagues, and leaders. Taylor completed her Ph.D. in Leadership Studies from the University of San Diego, and her M.S. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from San Diego State University.

Dr. Taylor Peyton is an Assistant Professor at Boston University’s School of Hospitality Administration, where she teaches leadership and human resources. She is also principal of Valencore, a leadership development firm that specializes in soft skills training for executives of various industries. Taylor has published peer-reviewed articles and has authored over 40 research studies, presenting findings to academic conferences and to general audiences. Her research interests include employee authenticity and emotions, organizational leadership, passion for work, and power use in organizations. She studies employees’ psychological experiences — or inner life — at work, specifically with regard to their emotional regulation and experiences of authenticity as they interact with their customers, colleagues, and leaders. Taylor completed her Ph.D. in Leadership Studies from the University of San Diego, and her M.S. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from San Diego State University.