C-corporation Hotels vs. Hotel-REITs: A Theoretical and Practical Comparison

Tarik Dogru

What are the main differences between C-corporation hotels, such as Marriott, Hilton, and Choice, and Hotel-REITs like Diamond Rock, Felcor, and Host? What are the potential growth opportunities in these hotel structures? This article attempts to answer these questions from a theoretical and practical perspective by comparing two corporate structures, their business models, financing, cash holdings, and investment policies along with their profitability and growth prospects.

Corporations undertake investments in a variety of forms to expand the business and create value for stockholders. The organizational form of franchising is the prevalent mode of expansion in the hotel industry, specifically in the United States (US). Many hotel chains started with few wholly-owned establishments, yet they expanded through franchising (or a combination of franchising, management agreements, and licensing). Expansion through a franchising business model does not require substantial capital investments—in fact, it reduces the required capital expenditures of the franchising chain, thus allowing investments that require financing beyond the available internal funds. Franchising also enables firms to expand into foreign markets while bearing little or no capital investment risk, because the risk is shifted to the franchisee in exchange for the franchisor’s expertise and brand name.

While the reasons why firms expand through franchising are not yet entirely proven, there are two established theories that seek to explain why firms adopt franchising investments. First, capital scarcity theory posits that small and young firms cannot easily raise external financing to fund their growth, and thus adopt investment franchising because it requires little or no capital investment (Oxenfeldt & Thompson, 1968). Second, the agency theory of franchising postulates that firms adopt franchising investment due to high monitoring costs of managers (general managers, in the case of hotels) when firms own the hotel (Rubin, 1978). Thus, firms prefer franchising over the company-owned divisions to avoid the high monitoring cost of general managers (Brickley & Dark, 1987). The agency theory of franchising further argues that franchising units have cost of free riding on the trademark, and as such will prefer franchising whenever the cost associated with franchising is lower than the monitoring cost and vice versa. That is, a hotel firm’s CEO has to determine whether monitoring the general manager or the franchisee is costlier prior to making an expansion decision.

Although many studies have tested the postulations of these theories, empirical results are inconclusive, reporting support for both the capital scarcity and the agency theory of franchising. The main reason for mixed and inconclusive results could be that the motives of firms are not comprehensively explained in these potentially outdated theories. Monitoring, whether for franchisees or general managers, is not as difficult as it used to be due to the ability of enhanced technology to obtain immediate, reliable performance data from the hotels and guest feedback through email or even from social media. Also, the capital scarcity theory of franchising was offered on the grounds that firms that expand via a franchising business model are young and small but have the potential for growth. However, the majority of hotel chains are publicly traded, and raising debt or equity is relatively easier if firms have a proven method of business or a recognized brand name.

Although we cannot simply discard the existing theories, they should be improved and modernized to better explain firm behavior. While a more comprehensive franchising theory applicable to different industries has yet to be developed, the hotel industry has specific features that may help to explain franchising choices in this segment of the hospitality industry. One of the arguments for why hotel firms adopt franchising is that hotel chains shift the capital investment risk to franchisees and receive risk-reduced cash flows from the operations. Although the stream of cash flows will obviously be lower, hotel chains can increase their sources of revenues in a compounded way through franchising more outlets in various locations. This strategy provides a fast-growth expansion that could make up for the opportunity cost of owning the hotel instead of franchising, but with much lower risk. It also allows hotels to rapidly meet the market demand by introducing new brands in a variety of segments, which further generates revenues for hotel chains. Considering the link between the hotel industry, macroeconomic conditions, and the industry’s unique characteristics, franchising becomes particularly beneficial during economic downturns for hotel chains.

In addition to a franchising business model, which is usually in the form of C-corporation, many hotel firms choose to be treated as Real Estate Investment Trusts, or so-called Hotel-REIT or Lodging-REIT. The chief difference between Hotel-REIT and traditional C-corporation legal structures is that stockholders of Hotel-REITs are exempt from corporate taxation on distributed dividends, whereas C-corporation hotels must pay corporate taxes on dividend payments. However, to be eligible as an REIT, the hotel company must meet certain obligatory conditions of the Internal Revenue Code regarding the asset ownership, income generation, and most importantly dividend payout ratio. Simply put, REITs must distribute ninety percent (90%) of their taxable income to stockholders every fiscal or calendar year. Although dividend distribution requirements offer a tax shield to the shareholders and provide regular dividend streams, this regulation may cause difficulties for Hotel-REITs in the times of expansion. That is, Hotel-REITs are more likely to seek financing through external channels (e.g., corporate debt or equity) for further expansion because these hotel firms will have only ten percent of their net income as retained earnings. Furthermore, Hotel-REITs bear the high risk of real estate investment, which requires ongoing maintenance and regular refurbishment to sustain the quality. Hotel-REITs might be an attractive investment choice for those who enjoy regular dividend payments—as John D. Rockefeller put it, “Do you know the only thing that gives me pleasure? It’s to see my dividends coming in” (Lynch, 2010). Nevertheless, investing in Hotel-REITs is relatively riskier.

Another means of business expansion is mergers and acquisitions, which are one of the most common investment methods and generally require substantial capital investment, as opposed to expansion via franchising. Hotel firms commonly use mergers and acquisitions as a prevalent corporate investment strategy to accelerate their expansions. Acquisitions, however, could be value-increasing or -decreasing projects for the firm depending on the CEOs’ motivations (Bebchuk, Cohen, & Ferrell, 2006). For example, the CEO of a hotel firm with poor corporate governance mechanisms (with no or less than 5% institutional investors in the firm) reacts negatively to acquisition announcements, since such acquisitions are perceived to be in CEO’s best interest and not that of the shareholders. Nevertheless, we also found that the quality of corporate governance does not matter in Hotel-REITs, and that REIT corporate structures actually could be adopted to align CEOs’ interests with those of shareholders (Dogru, 2017).

C-corporation Hotels vs. Hotel-REITs

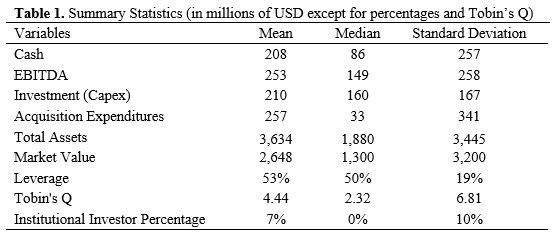

The sample of this study consists of lodging companies that are publicly traded in the New York Stock Exchange, American Exchange, or NASDAQ. The sample was limited to firms with financial information available on the COMPUSTAT annual database. This database covers firms’ annual financial reports—such as balance sheets, income statements, and statements of cash flow—which include variables used in this study. Table 1 presents summary statistics (i.e., mean, median, and standard deviation) of the variables for the C-corporation hotels and Hotel-REITs combined to illustrate the liquidity, financing, investment, profitability, and growth prospects of the publicly traded hotel firms.

On average, a hotel firm holds around $86 million in cash, with a substantial divergence between companies as the median value is much higher than the mean value. EBITDA, which is a measure of the operating or financial performance of a company, is $253 million on average, but with some deviations among individual firms. The measure of investments or capital expenditures (Capex) show that, on average, hotel firms spend $210 million on existing buildings or land for refurbishment and maintenance. Acquisition expenditures, which is another measure of investment, illustrates that hotel firms spend about $257 million to expand their operations through additions of new buildings or lands into their portfolios. The total assets and market value figures show the size of the hotel industry and that, on average, hotel firms’ total assets accumulate to $3.6 billion, with an average market value of $2.6 billion.(It should be noted that there is an extremely high deviation among hotel firms in terms of size.) The leverage indicator shows that hotel firms have 53% leverage. In other words, hotel firms’ assets are mostly financed with debt. Although this figure shows that hotel firms are financially levered, we would expect this figure to be closer to 60-70% due to the capital-intensive nature of hotel industry. Tobin’s Q is a proxy often used to determine the growth prospect of a firm. A value below one indicates a mature firm with little or no potential for growth, whereas a value higher than one suggests that the firm has potential for future growth. On average, Tobin’s Q is 4.44 in the hotel industry, suggesting that the hotel industry is a growing sector and has great potential for growth. On the bottom of the table, the shareholding percentage by institutional investors in hotel firms provides some insight into the quality of corporate governance in hotel firms, as well as the attractiveness of the industry to professional fund managers. A firm with more than five percent institutional ownership is considered to be well-governed; according to this study, hotel firms on average seem to be well-governed, making the industry an attractive sector for professional investors. Nonetheless, some hotel firms seem to have no institutional ownership, as the median value of this variable is zero. While some financial advisers, such as Peter Lynch, are proponents of firms with no institutional ownership, recent empirical studies in corporate finance and hospitality finance literature provide contrary evidence to support institutional ownership (Dogru, 2017; Franzoni, 2009).

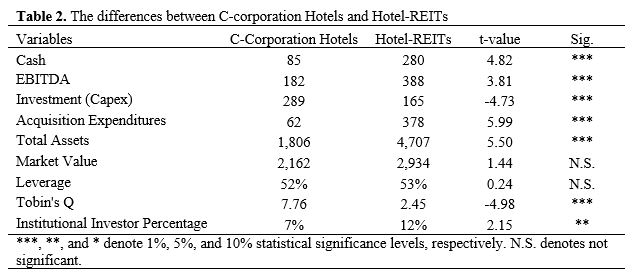

Although combined figures provide insights to the hotel industry, further examination is required to determine the differences between C-corporation hotels and Hotel-REITs. Table 2 presents the results from the mean difference (also known as the independent sample t-test) analysis. Overall, the results show that the differences between C-corporation hotels and Hotel-REITs are statically and economically significant. According to these results, C-corporation hotel firms keep lower cash ($85 vs. $280) and have higher capital expenditures ($289 vs. $165), but they make fewer acquisitions ($62 vs. $378). Hotel-REITs keep more cash than C-corporation hotels—probably because these hotels need cash to take advantage of possible investment opportunities as they arise. The lower Capex amount in Hotel-REITs is parallel with expectations, as these firms have limited hotels, whereas the number of properties in C-corporation hotels are greater.

The EBITDA figure shows, however, that Hotel-REITs perform better in this area compared to C-corporation hotels ($388 vs. $182). C-corporation hotels are also smaller in both asset size ($1.8 vs. $4.7) and market value ($2.1 vs. $2.9) compared to Hotel-REITs. Both Hotel-REITs and C-corporation hotels are almost equally levered (52% vs. 53%). Although both C-corporation hotels and Hotel-REITs seem to be promising in terms of the future growth prospects, the former surpasses the latter by the measure of Tobin’s Q (7.76 vs. 2.45). Nevertheless, Hotel-REITs have higher percentage of institutional ownerships (12% vs. 7%), which suggests that Hotel-REITs on average have better corporate governance mechanisms and that professional fund managers favor Hotel-REITs over C-corporation hotels. This is because Hotel-REITs provide dividend payments on a regular basis, whereas dividend payments at C-corporations are at the discretion of CEOs.

Recently, the hotel industry has experienced six years of impressive growth and is projected to enjoy such expansion in 2017, albeit with a slowing pace. The growth was mainly induced by the surge in the overall economy, both within the US and in the world. The descriptive analysis in this article shows that the hotel industry has significant growth prospects for the future, and—as this study has shown—different avenues for growth that each contain advantages and disadvantages. For example, Hotel-REITs seem to have better operational performance and better corporate governance mechanisms but higher risks and lower growth opportunities. As Peter Lynch stated, “in cases where you have to spend cash to make cash, you aren’t going to get very far.” On the other hand, C-corporation hotels seems to have greater growth prospects, as they can relatively easily increase the number of franchised hotels for a firm, enter into management agreements, and even introduce a new brand to the market.

To conclude, challenges like cyclicality and competition within the industry are poised to play a significant role in the future of hotel investments. Yet, there are new (actually, rather old now) challenges the industry players are facing, chief of which is the so-called sharing economy. While the cyclicality of the industry is likely to affect both corporate structures, Hotel-REITs are more likely to be affected by the sharing economy, as they do not hold a highly diversified portfolio of hotels compared to those of C-corporation hotels. Empirical analysis is required to prove or refute these postulations; however, I believe that expansion, regardless of the corporation structure, is likely to continue in the hotel industry unless a significant hike in the interest rate occurs or we enter into a recession period, which is not projected in the short term.

Tarik earned his Ph.D. in Hospitality Management from University of South Carolina, and holds Master’s degree in Business Administration from Zonguldak Karaelmas University in Turkey.Prior to joining the Boston University School of Hospitality Administration faculty, he was an adjunct faculty at University of South Carolina (2013-2016) and research assistant at Ahi Evran University (2009-2012) in Turkey. He has taught a variety of courses, including Economics, Finance, Accounting, Hospitality, and Tourism in business and hospitality schools. He is a Certified Hospitality Educator (CHE) and holds Certification in Hotel Industry Analytics (CHIA) from American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute. Tarik’s research interests span a wide range of topics in hospitality finance, corporate finance, behavioral finance, real estate investment trusts (REITs), hotel investments, tourism economics, and climate change.

References:

-

Bebchuk, L., Cohen, A., & Ferrell, A. (2006). What matters in corporate governance? Review of Financial Studies, 22(2), 783-827. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhn099

-

Brickley, J. A., & Dark, F. H. (1987). The chioce of organizational form: The case of franchising. Journal of Financial Economics, 18(2), 401-420.

-

Dogru, T. (2017). Under- vs. over-investment: Hotel firms’ value around acquisitions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(8).

-

Franzoni, F. (2009). Underinvestment vs. overinvestment: Evidence from price reactions to pension contributions. Journal of Financial Economics, 92(3), 491-518. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.06.004

-

Oxenfeldt, A. R., & Thompson, D. N. (1968). Franchising in perspective. Journal of Retailing, 44(4), 3-13.

-

Rubin, P. H. (1978). The theory of the firm and structure of the franchise contract. Journal of Law and Economics, 21(1), 223-233.

-

Lynch, Peter. (2000). One Up on Wall Street: How to Use What You Already Know to Make Money. Simon and Schuster, New York.

12 comments

It’s remarkable to visit this website and reading the views

of all friends regarding this paragraph, while I am also eager of getting knowledge.

Thanks For Sharing The Hotel Comparison Blog it’s really very helpful. Also Visit:- Magento 2 Admin Email Notification

It’s remarkable to visit this website and reading the views

Pamper yourself in a rooms to rent in dubai with a range of unrivaled amenities and services. Lounge by our rooftop pool while soaking in the panoramic vistas, stay active in our fully equipped fitness center, or rejuvenate with a relaxing spa treatment. Our attentive staff is always on hand to cater to your every need, ensuring an elevated and personalized experience.

These two hotels target the high-end customer segment, so their seterra service quality is also very good.

Explore the revamped UI and intuitive interface of Flixeon Free movies app that uses Material Design. This makes it superior to any other similar app both in terms of looks and performance.