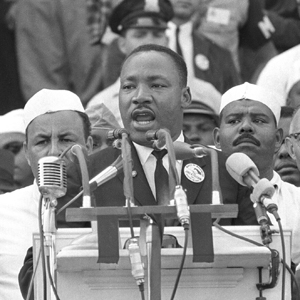

Earlier this year, the Boston Landmarks Orchestra was searching for an American Sign Language interpreter to translate Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. The orchestra was planning a concert commemorating the speech’s 50th anniversary and approached Christopher Robinson, a staff interpreter at BU’s Disability Services, about the job. But Robinson had a better idea: why not place native ASL users on stage and base their interpretations on an official ASL translation of the speech?

The BLO liked the idea—the only problem was that no official translation existed. Robinson had a solution for that as well: he suggested Richard Bailey, for whom he regularly interpreted African American studies courses.

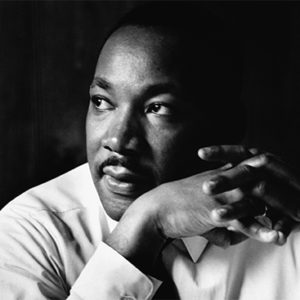

Bailey (GRS’13), a native ASL user who is biracial, was studying the writings and speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) as part of his master’s level research on identity and representation. He was willing to create an official translation, but there was a catch: it would have to be recorded, and Bailey was camera-shy.

“I was fine with the idea of working on a translation and handing it over to someone much more experienced with working in front of a camera,” Bailey says. “Or more photogenic. Probably a mix of the two.” But as he began to pore over the speech, which the King estate released to him with its full blessing, his reluctance to appear on camera dissolved. “After a while, you start to get a little protective of what you’ve created,” he says, “and I think that changed my mind-set about being in front of the camera.”

Bailey finished videotaping his translation in May, with Robinson functioning as cameraman and editor. Local performance interpreter Misha Blood has since studied Bailey’s translation to prepare an interpretative dance and ASL poetry set to Lee Hoiby’s composition I Have a Dream, which will be performed tonight during the BLO’s free concert at the Hatch Shell. Bailey’s ASL translation video will play on a jumbotron at various points during the concert as well. (Native ASL users will be on hand to interpret other pieces featured in tonight’s concert, including a performance of Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait and a rendition of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”)

Having an official recorded ASL translation of King’s speech fills a critical void in the education of deaf children. “There’s not a lot of ASL translations of historical speeches, especially as an educational tool,” Bailey says. “I don’t remember seeing anything like this growing up. I had access to subtitled or interpreted versions, sure, but you just feel like something’s missing or it’s uninspired.”

The video of Bailey’s ASL translation of the speech will be digitally archived at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change, in Atlanta, and will be available on the BLO website and on DVD at the Howard Thurman Center, BU’s multicultural center.

Bailey’s translation, Robinson says, is especially rich because of his deep knowledge of ASL, his cultural competency, and his academic credentials. Students will be able to tackle it as literature, he says, to “unpack it as if it were a book.”

In researching the speech, Bailey realized that “Dr. King, while still optimistic, was also increasingly frustrated with being stonewalled, and that frustration was beginning to show,” he says. “At the same time, you also start to see a widening of his platform, from civil rights in the United States to a more global outlook. It’s really fascinating to see someone’s outlook on the world evolve in response to the conditions they’re in.” In preparing the translation, he says, he had to carefully research and weigh the historical, political, and cultural context King was writing in before rendering his words into ASL.

Bailey found that some elements of the speech required a more liberal ASL translation. King used a metaphor early in the speech about promissory notes and checks to discuss the denial of civil rights to African Americans, but Bailey realized that people today live in a world of electronic transfers and debit cards. “I understood that he was not speaking about money,” he says, “but the currency of freedom, and that in the United States, freedom and liberty were the ‘riches’ of the country.” His translation reflects that core message. He also incorporated into his translation the proper ASL facial expression and body positioning to convey King’s sermonic tone and grammar.

While Bailey’s translation makes its world premiere tonight at the Hatch Shell, the goal is for it to live forever as a resource to the deaf community. “The people who were hearing the speech at that time,” Robinson says, “understood the code messages in the speech that told people to mobilize.…This is an opportunity for deaf kids to get access to the speech, appreciate it in their language, and generate a conversation about mobilizing as a minority population.”

Bailey hopes his work will inspire more native ASL users to translate historic speeches. “I want students to feel like they actually have a stake in the world around them,” he says, “and also be able to have full access to iconic moments in history in their own language.”

The Boston Landmarks Orchestra’s “I Have a Dream” 50th Anniversary Concert is tonight at 7 p.m. at the Hatch Shell on the Esplanade, 47 David G. Mugar Way, Boston. The concert is free and open to the public. The concert will conclude with special guest Governor Deval Patrick narrating Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait.

The “I Have a Dream” speech is truly iconic. I have lived in Washington for 10 years now, and it has evidently moved on a lot from 50 years ago.