On August 2, the first of two sickened American health care workers was flown from Africa to a special containment unit at Emory University. Despite the risk of infection, medical personnel continue to travel to West Africa to help bring under control the worst Ebola outbreak on record, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) has killed more than 900 as of August 6. WHO plans to spend $100 million to fight the outbreak, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will send 50 more disease control workers. In this weeklong Special Report, Bostonia talks to Boston University researchers in several fields about why medical personnel confront the risks; the ethical and political dilemmas presented by the outbreak; how the virus kills; efforts to design effective therapies; and other aspects of this unprecedented outbreak of Ebola.

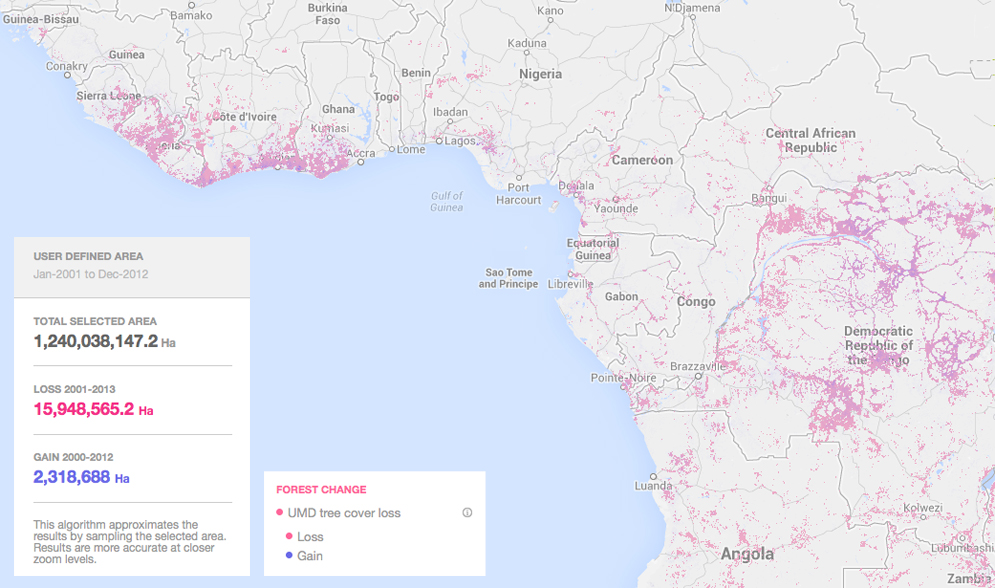

Human impact on the environment may be partially to blame for the deadliest-ever Ebola outbreak spreading through West Africa, researchers say. Global warming, logging, and road construction have put humans in closer contact with infected bats and gorillas. In a 2012 study in the Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, researchers wrote that “the increase in Ebola outbreaks since 1994 is frequently associated with drastic changes in forest ecosystems in tropical Africa,” and went on to note that “extensive deforestation and human activities in the depth of the forest may have promoted direct or indirect contact between humans and a natural reservoir of the virus.”

For historical context on the virus and the role that deforestation and human activity may have played in the current outbreak, Bostonia spoke with James C. McCann, a scholar on the history of the food, ecology, and agriculture of Africa. He is a faculty fellow for the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, associate director of the African Studies Center, chair of archaeology, and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history. He is also a Guggenheim and Fulbright Fellow. His numerous books include Green Land, Brown Land, Black Land: An Environmental History of Africa, 1800–1900; Stirring the Pot: The Tastes and Textures of African Cookery; and Maize and Grace: Africa’s Encounter with a New World Crop, 1500–2000, which won the 2006 George Perkins Marsh Prize as the best book on environmental history from the American Society for Environmental History.

Bostonia: How is human activity in Africa spreading the Ebola virus?

McCann: With the Ebola outbreak in the Congo in 1995, tropical medical specialists were associating it with monkeys and forest-based activities, and now in this outbreak they have shifted to bats as a key link to transmission. This is a situation that is quite fluid because they understand the disease and what it looks like when there is an outbreak. The question is, how do you treat it, how do you avoid transmission?

If you look at earlier examples of not just forest change, but ecological change brought on by human activities, this bears some resemblance to the 1918 Spanish flu. That was a communicable disease with no vector involved; in other words there was not an insect vector that would explain the transmission, as with mosquito vectors and malaria. It’s a hemorrhagic fever that comes with contact with bodily fluids, even if exchanged by touching or by breathing.

If you follow the Spanish flu’s movement, it moved according to lines of transportation and communication. So people who got the disease, you could follow railway tracks. It came to Africa via a ship, ironically to Sierra Leone, one of the current areas affected by Ebola.

If we look at this [Ebola outbreak] ecologically, there are two different forest systems in play. In the 1995 outbreak in the Congo, it was one outbreak, people died at a very high mortality rate, but it seemed to have died out. That outbreak occurred in the Congolian forest. Now Ebola has found its way into the Upper Guinea forest, which is a different forest system. But it seems to be spread, just in terms of a hypothesis, because of the interaction between human changes and landscape. The presence of bats and other forest-dwelling mammals seems to be a key factor. The forest, which is in transition from either deforestation or other kinds of interaction between the forest and settled areas, seems to be the factor why Ebola is suddenly popping up again.

Forest change in West Africa may have brought humans closer to forest primates, which are natural reservoir of the Ebola virus. Photo by Flickr user jbdodane

Is deforestation a major issue in western Africa?

The area where the recent Ebola outbreak is taking place is actually going through a process of reforestation, or rather forest change. A lot of the area, which is inhabited, is regenerating forest. With that being the case, it’s a transitional zone where people are coming into closer contact with the forest ecology. Just like I have raccoons and skunks near my suburban house, that kind of local landscape transition promotes new kinds of habitat and the new kinds of interactions between humans and the natural world that have been taking place in the West African forest ecology. So I wouldn’t say it’s deforestation, I would say it’s landscape change. Deforestation is too simplistic a term.

Our reaction, understandably, is to respond to Ebola as a biomedical crisis, and to some degree it is, and the solution may come from the immediate treatment of patients. But the larger issue is the transition in ecological terms of human-natural interactions. I think that’s where the longer-term solution will come from—understanding what happens when you begin to transform human ecology.

In your book Green Land, Brown Land, Black Land, you discuss the dangers of forest change, changing climate, and rising ocean temperatures. What other human ecological issues is Africa dealing with?

There are massive changes that have to do with population growth and movement, urbanization, which is not simply the removal of everything. It’s the increased interaction between the natural world, which includes factories of disease, and human settlement. When you have an area of forest that is either preserved or interacts more directly with humans, that’s where we see Ebola, both in the 1995 outbreak and now.

These areas have also just been through political crises to a large degree. Guinea has serious economic problems that accompany political unrest; Liberia went through civil war and a dislocation of all of the practices of health care. With those things going through a transformation, I think that’s why Ebola suddenly emerges. It happens to be a very deadly virus with a high mortality rate, so it really captures the world’s attention. It’s especially capturing people’s attention because doctors are coming down with the disease, which was also true with influenza earlier in the 20th century.

What are some of the lessons learned from previous outbreaks and how are those informing how we deal with this current crisis?

We’ve learned more about it and identifying the transition from the human links to its setting in nature. In this case it’s either bats or the eating of forest materials, proteins that may have promoted it. But simply the changing context of the ecology brings about disease. Malaria, after all, came out of the beginning of the movement of the forest very early on. For malaria, it was early contact between the people who were coming out of a forest and had natural immunity and people who didn’t have the immunity. It has to do with the human ecology interface. Ebola is one version of that, but there are many others.

The lesson is that ecology really matters for health. It’s as much ecology as it is biomedicine. That, I think, is the lesson. Sure there’s a biomedical understanding of malaria, but it doesn’t help us suppress or understand the disease. Ebola may well be a similar situation. The historical analogy will be valuable to keep in mind.

Does West Africa have the infrastructure in place to fight this outbreak?

It’s very limited, partially because the infrastructure for health care delivery is not there. When you have an outbreak, there are people who don’t have access to health care, or their health care is very limited. That’s a connection to politics. And the role of local belief systems about disease may be at play here, too. On the news we are seeing many mission health centers, but not well-supplied clinics, in Guinea and Liberia. The delivery of primary health care is an issue. The first doctors who have contracted Ebola are missionaries, who often are the first to treat patients in affected areas.

The setting is the forest ecology. The Upper Guinea forest is separate from the Congolian forest, and there are different characteristics, but nonetheless, people are moving out, clearing land for settlements and small towns. It creates a whole new mix of things, out of which comes disease, like Ebola.

This week, the Liberian government has started to insist that Ebola victims be cremated. Does this fall in line with West African beliefs?

You’re finding that cremation is suggested by the medical folks as a way of trying to stop transmission. Cremation is not a usual practice; in cities, it’s becoming a little more common, but it’s not a practice in most African societies. That would be a Christian burial. The burial practices vary from society to society. If you’re Roman Catholic or Muslim and you live in rural Guinea, you’re likely to be less receptive to the idea of cremation than people in other areas. Culture will play a role in treatment and response. There is a great variety of practices in Africa. In general, it’s fair to say that cremation is not a universally applicable way of dealing with the dead.

Tomorrow: Why Researchers Need to Work with Deadly Pathogens. Read all stories in our series, “Battling Ebola” here.

Related Stories

Battling Ebola: Grading the Global Response to the Epidemic

BU infectious disease expert lauds efforts under daunting challenges

Battling Ebola: The Ethical Issues

Experimental drug use treatment at heart of the debate, says BU’s Annas

Battling Ebola: Tracking the Virus

Current Ebola outbreak defies earlier models

Post Your Comment