A cofounder of Blue White Future, a movement calling for a two-state resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Amichay Ayalon is the first to say that the situation is volatile and complex beyond description. Ayalon was on campus in October to speak with students at the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies and to deliver the annual Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Lecture. Even as Ayalon spoke, tensions in Jerusalem flared yet again, this time over who can and can’t pray at a site holy to both faiths that Jews call Temple Mount and Muslims call Haram Al-Sharif. Israel is a very small country, but “don’t try to understand us,” the former head of Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, and retired admiral told students in a Judaic Studies class, Israel: History, Politics, Culture, and Identity, at the Wiesel Center. “We don’t understand ourselves.”

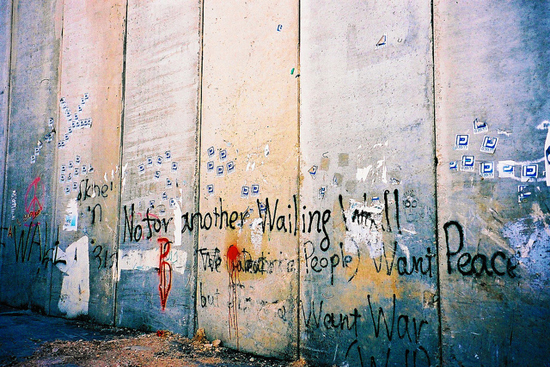

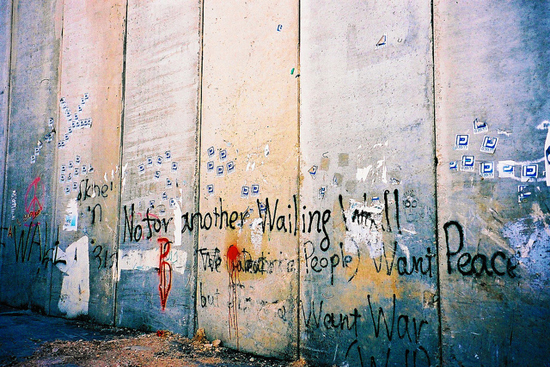

Also a former member of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, Ayalon is a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute. He and Blue White Future are advancing what Ayalon calls “a new paradigm,” a two-state plan which, according to the organization’s website, calls for Israel to cease all new settlements east of the separation barrier, which Israel built along the 1949 Armistice Line or “Green Line,” and in Arab neighborhoods in East Jerusalem; to consider transferring areas east of the barrier to Palestinian control in a gradual, monitored, and supervised manner; to enact a law that allows for “voluntary evacuation, compensation, and eventual absorption of settlers presently residing on the eastern side of the security barrier”; and to “prepare a national plan for the absorption of the settlers who would relocate to Israel proper.”

The son of a Transylvania-born Zionist who emigrated in the 1930s to what was then the British Mandate of Palestine, Ayalon, whose personal history parallels that of the Jewish state, recalls many childhood days spent in a bomb shelter as Syrian bullets flew over the border to the kibbutz his parents helped create in the Jordan River valley. Of his service in the navy, he says, “I fought too many wars and lost too many people.” A highly decorated sailor who still carries himself with a military bearing, he was severely wounded in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, known as the Six Day War.

Ayalon, who has called for an evacuation of Jews in settlements east of Israel’s West Bank security fence, says he realized something was terribly wrong after the first intifada, or Palestinian uprising, which lasted from 1987 to 1991. It was then that he saw ordinary Palestinians take to the streets in frustration and anger.

While addressing the Judaic Studies class, Ayalon was asked by a student under what circumstances the use of violence is necessary. Ayalon responded, “I have no idea. We always know it in retrospect.” But in the ongoing conflict, Ayalon sees, on the part of Israelis, an unnerving paradox. On the one hand, Jewish identity reflects humane social values, he says, on the other a belief in a God-given entitlement to the land. It’s a belief he doesn’t share, but his main point is pragmatic. “We jump to discuss security,” he says, “but we don’t understand that our borders should reflect identity, not security. And when the border is the Jordan River—on that day—we will no longer be a majority in our own state, and we will lose our identity.”

Ayalon made Israeli history when he became the first head of the largely covert Shin Bet (its security and counter-terrorism role is closer to that of the US Secret Service than the FBI) whose name was made public during his service. He became widely known outside of Israel for his role in the Academy Award–nominated documentary The Gatekeepers and is a frequent international speaker and op-ed contributor.

He laid out his two-state plan in the New York Times last April, condemning Hamas but writing that, “in the end, we Israelis have to understand that in the war we are fighting, victory is not achieved on the battlefield. We will have security only when the Palestinians have hope.” Ayalon does not shy away from the word “apartheid” to describe Palestinians’ fate if there is no accord. “That is why,” he told the students, “we must have a political horizon and we have to begin to create a reality of two states, even if we initially have to do it on our own.”

The Israeli–West Bank separation wall, built along the so-called “Green Line,” is a stark reminder of ongoing Israeli-Palestinian tensions. Photo courtesy of Flickr contributor Sarahtz

Bostonia sat down with Ayalon at the Wiesel Center to discuss the virtues of a two-state strategy, and why it is such a hard sell in spite of widespread support.

Bostonia: If you polled Israelis today about a two-state solution, would the majority support it?

Ayalon: An opinion poll today would be very, very complicated. Why? On one hand, if you will ask people—on both sides—whether they support the idea of two states, a majority will say yes. But it is very important even on what day you ask. If it is after an event that influenced the feeling, it might change every day. And if you ask on the same day, do they believe that we should see this solution in our lifetime, the majority on both sides will say no. And if you ask whether Palestinians deserve it, I believe most Israelis will say no. It’s very complicated.

But it’s safe to say most Israelis want peace.

We’re laundering our dictionary words every day. I’m sad to admit that peace is not a word that most Israelis are using these days. We abused this concept of peace. We had something like peace now for too many years. Most people believe that if you ask Israelis what they want, they’ll tell you, “We want security.” But for me, security is secondary to our identity. I believe that we are strong enough to come out and to say that we have to shape our identity and then to think how to secure it, and not vice versa.

Does Blue White Future hold sway with the Israeli government?

If you meet with our Knesset members one by one, a majority of our Knesset members accept our views. But when it comes to the way they vote, it is far from it.

Are Israelis resigned to the conflict as a part of life in their nation?

The problem is that I believe that many people do not feel a sense of urgency about a solution. Security is great. We are far from the first and second intifadas, when it was obvious that enough is enough. In two years we lost 1,300 people, I think 90 percent of them civilians.

Israel’s Iron Dome missile shield is kind of a metaphor.

Yes. Today, people are not dying in the streets. The economy is great. People are not eating identity. They will go out to demonstrate because of the rising price of living. But people do not go out to the street because of justice and identity. At least not many will.

I often read the statement: “Israel has no partners.” Do you agree?

The question is not whether we have or do not have partners. The question is what should we do tomorrow in order to create a partner. And I believe that every leader who accepts the idea of two states is a partner, even if I do not agree on certain issues. And [PLO chairman] Abu Mazen accepts the idea of two states. For me, that’s enough. I don’t want to waste time on whether he recognizes what happened during the Holocaust or not. So what we present to Israelis is, let’s move from a language of blame to a language of responsibility. We have not done enough of this in the last 20 years.

Many believe that some Arab nations have a vested interest in the conflict continuing. Is that true for some Israelis, too?

Yes, of course. Even if I don’t know who, I have to assume there are groups that are taking advantage of this conflict. Whether it is because of status, whether they are getting elected as a result of this atmosphere, or whether they are getting money out of it, it is always the same. But this is not something that I waste my time on.

Why is it in Israel’s interest to have a separate Palestinian state?

It is much easier to negotiate with a state on exactly where the border is between us. It’s much easier to negotiate with a state than with an organization. I believe that this is in America’s interest. I believe that this strategy will reduce radicalism and fundamentalism and will create pragmatism. It will empower the American influence in the Middle East. People ask me, “Why do you care about the Palestinians?” And I say look, all of us, first and foremost, are human beings. And we have to balance between our human values and Jewish values, which for me are the same. This is my way of understanding Judaism. This is what I understood from my parents, why they came to this place. The idea is to create a better society.

Related Stories

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

CAS class seeks to present all views in a volatile discussion

Brown Rejects Boycott of Israeli Academic Institutions

Warns that it politicizes the “robust exchange of ideas”

SED Student Helps Bring Israeli, Palestinian Youth Together

Dana Dunwoody puts her Frisbee skills to good use

Post Your Comment