During his 16 years at BU, Andrew Bacevich has become one of the University’s most public faces. The half dozen books he wrote while here—on the role of the United States and that of the US military in the world—landed the former Army colonel on television shows such as The Colbert Report and PBS’s Moyers and Company, while making him a staple of newspaper op-ed pages. His from-the-get-go opposition to the war in Iraq became especially poignant when his son, First Lieutenant Andrew Bacevich (CGS’01, COM’03), who had followed his father’s example by enlisting in the military, died in that conflict. His grieving father compared his son’s service with his own antiwar stance, writing, “As my son was doing his utmost to be a good soldier, I strove to be a good citizen.”

Bacevich, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of international relations and of history turns 67 next month. He will retire as of August 31, but he won’t vanish completely. His MOOC on the Middle East will launch in the fall, requiring him to be available online to students. He’ll also continue his participation in a history department lecture series–study group in the coming academic year.

“My wife and I like living in New England, so we’re staying here. We aren’t going to Florida,” he says.

BU was Bacevich’s third academic tour of duty, following a 1970s stint at West Point, his alma mater, and one at Johns Hopkins in the 1990s. His 23 years in the Army before that included service in the Vietnam War. In an interview with Bostonia, he reflects on his military and academic careers and the deteriorating situation in Iraq, where ISIS, a militant Sunni group that even al-Qaeda has disowned, has taken swaths of the country from the Shiite Muslim government of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki.

Bostonia: Why did you decide to leave BU at this point in your career?

Bacevich: I have emphatically enjoyed my time on the faculty. I’m exceedingly grateful for the way the University has treated me and my family. I am not leaving with any complaints. But I increasingly feel that I’m losing my edge as a teacher.

How does a teacher measure that?

It’s more of a gut feel than anything else. I don’t feel as much energy and enthusiasm as I did 10 years ago. Students deserve your very best. I’m not sure that I’ve got my very best to offer anymore. Along with that, I increasingly want to write more. That’s what gives me satisfaction in life. To conjure up ideas and then to compose, to do the hard work of translating an idea or an insight into an argument and into readable prose, is something that I find to be a great challenge, but a source of considerable satisfaction. To a BU student, 67 seems very old, but if you’re 67, it doesn’t seem very old. We all have a limited time available, so I decided that for whatever time I do have left, I want to devote my energies to writing books and articles.

Bacevich, here teaching an international relations class, says his enthusiasm for the classroom has ebbed. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

The military and academia seem to be utterly different cultures. What’s the difference between the two, and was it difficult straddling both?

The two are different, but in some respects quite similar. Academia is a profession that operates in an institutional setting. So does the military. When you’re part of the Army, you’re part of a very large institution that has its own culture, deeply ingrained, and so too at Boston University. It has a lot of history and culture, and in order to be successful and to contribute, you have to learn that institution.

There are high expectations of performance in both. I have always been impressed by the seriousness of my colleagues at BU, who are excellent teachers. They take their responsibilities to students very seriously. I’ve also been impressed by their serious commitment to scholarship. Many times, they’re studying things that, in some cases, I’m not capable of understanding. You can’t help but be impressed by the extent to which people are committed to their research agenda, and work hard at it. Not because they’re going to get rich, but because they think it’s important. When you’re in the military, there is that devotion to the larger purpose for which the profession exists.

The biggest difference is that as scholars, our search for truth is rooted in expectations of freedom to think what we want to think and say what we want to say. Those are freedoms that have to be exercised responsibly, and I think that they are. As an academic, I’ve come to appreciate what it means to be free. In the military, that kind of freedom simply doesn’t exist. There are expectations of discipline and subordination and conformity, and need to be. We don’t want an army in which every second lieutenant gets up in the morning and figures out the best way to fulfill the mission. We want them to adhere to a common template of how things need to get done so that they can work as members of a team.

I think there’s massive misunderstanding between the two worlds. Professional military officers tend to see academics as pointy-headed, airy-fairy impractical. I suspect that many academics tend to not appreciate the amount of intelligence that is found in the officer corps.

In 1970, Army First Lieutenant Andrew Bacevich (right), with Sergeant First Class James Wright, was serving in the Vietnam War. Photo courtesy of Andrew Bacevich

In the 1970s, there was definitely an antimilitary feel on campuses. It seems like that has abated now.

There’s no question that it’s different. I am recognized as someone who used to be in the Army. That has never been a source of any kind of objectionable behavior. I always felt that I have been treated with the greatest respect, and I have been very grateful for that. I think there has been a change in attitudes toward the military on campuses, among students, among faculty.

There’s a need to improve the level of understanding in both directions. I don’t think people understand how hard academics work. When a member of our faculty is not teaching or does not have some specific campus duty, that person can stay home and work. Who knows what they’re doing? From an outsider’s perspective—You only teach two courses? You’re only in the classroom for six hours a week? And then all you have to do is hold office hours?—it sounds like a job that is so undemanding, and that’s an inaccurate perception. We work hard, not necessarily in things that the average person can see or appreciate, but we work hard in our discipline.

The other thing that people on the outside don’t appreciate is the enforcement of standards to remain a member of this profession. What a gift tenure is. Lifelong employment, for God’s sake. But to gain tenure or further promotion, I have been struck by the seriousness of the evaluation that members of this profession have to undergo before making it over those gates. Quite frankly, it’s much more difficult to gain tenure at BU than it is to be promoted to lieutenant colonel in the US Army.

Your recent op-ed said President Obama ought to forge a working understanding with the Iranians to contain ISIS.

It appears that Iran and the United States are signaling to one another that there’s a willingness to talk, not necessarily to collaborate. Let’s explore if there’s a convergence of interests enough to collaborate.

I tend to think that most American observers overstate the amount of leverage that we have in that part of the world. My analogy is with Nixon in China, recognizing that the People’s Republic of China and the people of the United States had a common interest, a common adversary: the Soviet Union. That transformed the strategic landscape. I just wonder if that’s possible in regard to Iran. A guy like Nixon would not be sitting around talking about whether or not we should use drones or manned aircraft to bomb ISIS. That’s a lesser question. It’s not worthy of a grand strategist. It’s just too bad there doesn’t seem to be anyone in Washington whose thinking is on that scale.

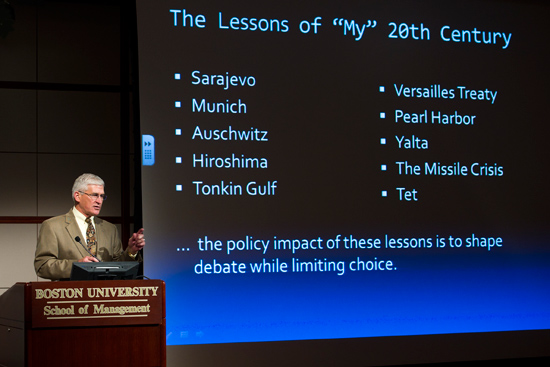

Bacevich’s knowledge of history has made him one of the University’s most prominent commentators on global affairs. Photo by Vernon Doucette

What was your proudest accomplishment at BU and your biggest disappointment?

I was able to write books, so they have enabled me to be very productive. The work has been very rewarding, and I’m grateful for that.

Disappointment? I have come to, frankly, a recognizing of how limited our influence is as teachers on students. These young people who come to us—they’re all wonderful and bright and eager and ambitious, but they are influenced by so many different things, things that are far more powerful than a professor in the front of the room pontificating. I’ve learned to be modest in my expectations of my ability to shape the thinking of young people. I’ll give you one specific example.

I think that the notion of American isolation is utter and complete fiction. We’ve never been an isolationist country. I have repeatedly tried to make that argument, and I know that I have persuaded no one. Because the students, when they watch TV or when they get the mythic version of history that says we were completely isolationist until December 7, 1941, absorb those messages and reject mine.

Think of the interwar period [between the world wars], supposedly isolationism’s peak. US forces are occupying the Philippines. The US Navy is running gunboats up and down the major rivers of China. We’ve got a US Army regiment in the outskirts of Peking. We occupy Panama to guard the canal. During the 1920s, US Marines are running the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua. How does that qualify as isolationist?

Do you have another book in mind?

The working title is America’s War for the Greater Middle East. The book will make the case that all of our military adventures and misadventures in the Islamic world since 1980, when Jimmy Carter propagated the Carter Doctrine [that the Middle East was a vital US interest], should be seen as one war. Think about the Cold War: it consisted of many different episodes—the Korean War, Vietnam, intervention in Grenada, the Berlin airlift. If you step back, you see that they’re all part of this larger struggle called the Cold War. When we group all these episodes together, we learn certain important truths. And I want to do the same thing with our military effort in the Islamic world from 1980 down to the present. The Lebanon intervention that culminated with the Beirut bombing in 1983, the intervention in Somalia that culminated in the Mogadishu firefight in October 1993, the invasion of Iraq in 2003: all of these and other things need to be seen as part of a single, coherent narrative of this war for the greater Middle East. The goal has been to impose America’s will on the Islamic world, with the expectation that the adroit use of hard power will yield that outcome. The Cold War, most of us would say, ended successfully. I believe that the war for the greater Middle East is doomed to fail. From a policy perspective, there’s an urgent need to reflect on what this war has yielded, what lessons we can take from it.

I think the term “terrorism” is an excuse not to probe more deeply into the question of who is the adversary, what kind of threat does he represent, and what are we trying to achieve. One could argue that despite all the mistakes the United States made in the Cold War, there was this idea of containment of the Soviet Union. With one exception, there has not been a unifying idea with our war in the Middle East. The exception is in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, where the Bush administration set out to transform the region, using American military power, with the intent to democratize it. They imagined the Iraq War as the first step in this grandiose project. It was an arrogant idea, an implausible idea, and it failed. It failed when the liberation of Iraq created such a catastrophe that even today, they’re still grappling with it.

Is it fair to say that there’s an alternative, legitimate goal of our antiterrorist efforts—to keep ourselves safe from another 9/11?

I think it’s reasonable. The agencies are supposed to be keeping us safe, and they’re supposed to be doing it at a reasonable cost that tries to keep faith with the ideals that we represent. It’s not clear to me why invading Iraq or occupying Afghanistan for more than a decade is necessary to achieve that purpose.

Related Stories

MOOC Probes a War You’ve Never Heard Of

Middle East course by BU’s Bacevich coincides with ISIS emergence

Why the United States Should Stay Out of Syria

CAS’ Bacevich: we’re “powerless” against “tsunami of change”

What Will a Leaner Military Mean?

BU’s Andrew Bacevich on the proposed new army

Post Your Comment