One month after the historic marches he led in Selma, Ala., Martin Luther King, Jr., arrived in Boston to demonstrate against the city’s festering school segregation. On April 23, 1965, in a light rain, he led singing protesters more than two miles, from the predominantly African American neighborhood of Roxbury to the Boston Common. There, he told a crowd of 22,000 that it was “the time to make real the promise of democracy.” The Boston Globe called it the city’s “first gigantic civil rights march.”

One man was close to his side throughout: pastor and activist Gil Caldwell.

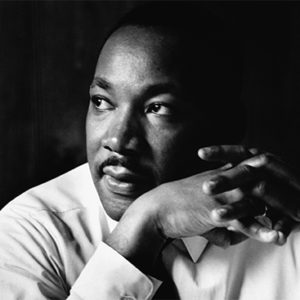

In the press photos of the day, Caldwell (STH’58) appears next to King (GRS’55, Hon.’59) as the civil rights leader addresses a growing throng in Roxbury, joins King in song at the head of a reported “mile of marchers,” and stands on a temporary Boston Common stage, fresh from introducing King to the crowd.

Caldwell was a self-described foot soldier in the civil rights movement: he marched on Washington, called for voting rights in the heat of the Mississippi summer, and walked from Selma to Montgomery. He later broadened his demand for equality, advocating for gay rights. In 2000, he was arrested twice for protesting the United Methodist Church’s policy that the “practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.”

Later that year, a brain tumor left Caldwell with nerve damage in his right leg. Now 82 and retired, he’s producing and starring in a 56-minute documentary, From Selma to Stonewall: Are We There Yet? The film, which is expected to be released this year, is an exploration of the similarities, differences, and conflicts between the civil rights and the gay rights movements. To Caldwell’s disappointment, not everyone who stood alongside him during the heyday of the civil rights struggle supports his advocacy of gay rights. Some dissenters are caustic; the more reasonable argue that the push for black justice is incomplete. But after a lifetime of striving against discrimination, Caldwell counters that no one deserves to be excluded in the drive for social justice.

Caldwell was born in 1933 in a segregated hospital in Greensboro, N.C. He grew up in a segregated neighborhood and was educated in segregated schools, later earning an undergraduate degree from North Carolina A&T State University, a historically black institution. The son—and the grandson—of a minister, he attended a black church (it would have welcomed whites, he says, but the welcome was never tested). In 1955, Caldwell tried to break the cycle of racial inequality by applying to study at Duke Divinity School in Durham, N.C. At the time, Duke didn’t accept African American students—and wouldn’t until 1961. Like so many other blacks in the South, Caldwell crumpled his rejection letter and headed North for a master’s degree.

At Boston University’s School of Theology, Caldwell sat for the first time in classrooms with students who were not black. It was, he says, a “new interracial experience…just a marvelous barrier-breaker for me.” He studied with two of King’s major influences—Deans Howard Thurman (Hon.’67) and Walter G. Muelder (STH’30, GRS’33, Hon.’73).

Rev. Gil Caldwell giving a guest sermon at Union United Methodist Church in Boston in September 2015. Photo by Cydney Scott

The first time Caldwell met with King was in 1958. The civil rights leader—by then a Time magazine cover star—was in town to make a speech, and Caldwell, vice president of the STH student association, decided to ask King to visit the University he’d left three years earlier. “I called the hotel where he was staying,” Caldwell says, “asking for Dr. Martin King. Lo and behold, they put the call in to his room and he picked up the phone.” King agreed to speak at the school. Caldwell can’t recall the topic, but he remembers relaxing with King and other students afterwards in the STH basement refectory. Unlike other famous people Caldwell has met since who were “impressed by their own charisma,” King wanted to learn about those sitting with him. Caldwell found himself “bonding with him and knowing that he would be a person I would love to follow.”

By 1965, Caldwell was pastor of Boston’s Union United Methodist Church and heavily involved in the Massachusetts division of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. So when King came to Boston in late April that year to meet with legislators and decry school segregation, it was Caldwell who presented him to the crowd on the Common.

In the years between the two meetings—and before joining Union in 1963—Caldwell had been the first black pastor of two predominantly white churches, in Bryantville and West Duxbury, both in southern Massachusetts. When he started in Bryantville, some families left the church; he visited them anyway. “You can imagine the tension at the door,” he says. Someone had planned a more sinister welcome: “The first day, I got an anonymous call saying there’s a bomb in the church.” He went looking for the device; the threat was an empty one.

Caldwell, who served four white and five black churches during his career, believes that living his life “against the white background” made him “more conscious of race or color” and more receptive to black theology. In 1968, he became a founding member of Black Methodists for Church Renewal and of the National Conference of Black Churchmen. His activism didn’t end in the ’60s. In 1971, he inaugurated his rap sheet while protesting a supermarket’s discriminatory hiring; in 1985, he was arrested again after condemning apartheid outside South Africa’s Washington, D.C., embassy.

When protesters disrupted the 2000 United Methodist Church annual conference in an attempt to overturn its policies on homosexuality, Caldwell joined them, ready once again to make a stand—even if it meant another spell in cuffs. He’d first confronted his views on gay rights in the late ’70s when activist priest Malcolm Boyd came out; Caldwell liked Boyd’s writings and decided his sexuality would do nothing to change that. He later became publicly involved in advocating for gay rights, because, he says, the movement merited a place alongside that for racial equality. “We can no longer engage in silo justice movements,” Caldwell, a prolific letter writer, wrote one of his colleagues in 2015. “Until all of us are free, none of us are free.”

He hopes his forthcoming documentary can bring the movements together. In the film, he joins author and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights activist Marilyn Bennett on a journey to Selma and other landmarks in the civil rights and gay rights movements. The two share their own stories, as well as those of other activists, religious leaders, and academics, exploring how the two movements intersect—and where they collide. In Selma, for instance, Caldwell talks about James Reeb—the white minister killed in the city in 1965—and his role as an ally of the black civil rights movement. Caldwell calls Reeb, with whom he flew from Boston to Selma, “the model for what I’m attempting to be as an ally-advocate of LGBT people and same-sex couples.”

When he returned to Selma for the documentary, Caldwell felt some in the city were reluctant to talk with him, wary of associating an emblem of the civil rights movement with a call for gay rights. He says he’s even received abrasive letters accusing him of betraying his legacy of civil rights engagement and of betraying King.

“I’ve been disappointed that many of my civil rights movement colleagues have not joined me in being ally-advocates of gay rights,” says Caldwell, who officiated at his first gay wedding in 2014 and is a former national board member of Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. “I am appalled and overwhelmed at how I think black persons in the Church hew to a literalistic interpretation of scripture on gays and lesbians, when a literalistic interpretation of scripture was what enslaved our forebears and racially segregated us.”

Others have argued there’s still too much to do in the fight against racism. Caldwell doesn’t disagree: his euphoria about the first black US president has been beaten down by the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, and others. “We’re repeating the past,” he says, “because we’ve not really exorcised it.” The United States needs to make reparations, including financial ones, he says, and “revisit its antiblack history and be honest about today’s antiblack reality; the truth of that effort would shape new responses and ultimate healing for the nation.”

But Caldwell is convinced that that doesn’t have to happen at the expense of equality for all.

With so much work still to be done, he isn’t giving up the struggle. “I’m hoping that what I say will speak to the future. How this old dude, Gil Caldwell, is living life on tiptoe, peering over to see what it’s like beyond.”

Watch a trailer for From Selma to Stonewall: Are We There Yet? here.

Andrew Thurston can be reached at thurston@bu.edu.

A version of this article will appear in the spring 2016 issue of focus.

Good article, much appreciated. However, it twice fails to ID another crucially important figure in the Civil Rights movement: the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, seen immediately to the right of the policeman. Abernathy was a constant & effective ally & adviser to Dr. King, & for many years was an equally important activist, if not as prominent.

If the Civil Rights movement is reduced to the efforts & exceptional qualities of one man (Dr. King), no matter how great, we risk misunderstanding its essence, As a Movement, it relied on the ongoing efforts of countless people, mostly little-known (unlike Rev. Abernathy back in the day) but dedicated to the cause of justice. Even King himself is misconstrued. His work & ideas must not be defined by one speech, one phrase (“I have a dream”). Still less was he a dreamer; he was shrewd practical politician whose thought continually involved in new directions. in his last year he also tackled issues of class conflict & militarism. Rank-&-file activists did not write bestsellers or give electrifying speeches; they expressed their ideas through action, making a true mass movement.

For more on these matters, see the following. FYI, Wade-Gayles was active here as a student at BU in the 1960s.

Ralph Abernathy, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down

Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom

Howell Raines, My Soul Is Rested

Gloria Wade-Gayles, Pushed Back to Strength