Kyna Hamill did not set out to debunk a cherished local myth about “Jingle Bells,” but the truth became a runaway sleigh.

At 19 High Street in Medford, Mass., a plaque commemorates the spot where James Lord Pierpont (1822–1893) supposedly wrote the popular holiday song, inspired by sleigh races on Salem Street, while sitting in a tavern in 1850. Hamill, an assistant director and senior lecturer in the CAS Core Curriculum who also teaches in the CFA School of Theatre, became interested in the “Jingle Bells” story while working as a volunteer with the Medford Historical Society & Museum. “Every December, we’d get a call asking to do a story about ‘Jingle Bells,’” she says. “I would pull out the file, and it was a very easy story to tell. Reporters loved that it was written in Medford.”

Reporters also love conflict, and so they were thrilled to learn that the Medford tale is contested by people in Savannah, Ga., where Pierpont is buried. The southerners insist that Pierpont wrote the jaunty winter anthem in that city, in late 1857, and led the first “Jingle Bells” singalong in a local church where his brother was pastor.

“This really bothered me, that it had two narratives,” says Hamill, who has lived in Medford since earning a PhD in theater history from Tufts. “I started digging.”

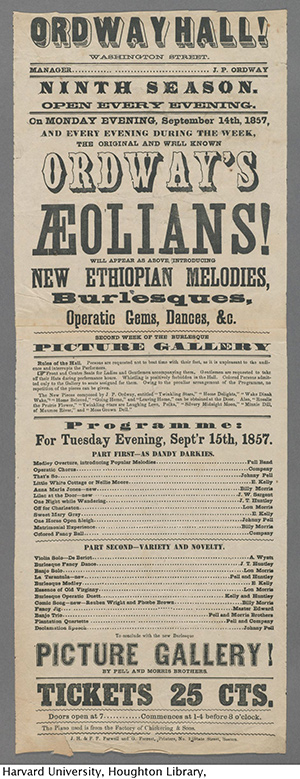

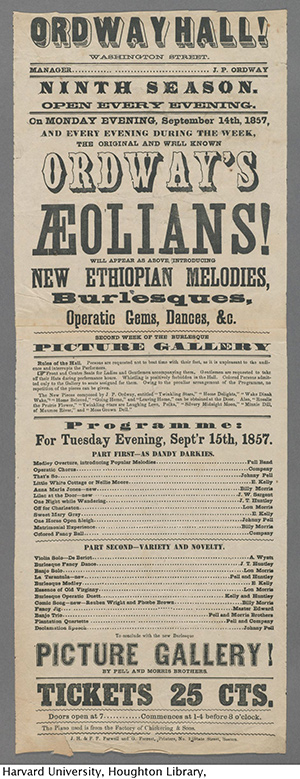

Playbill for the first known performance of “The One Horse Open Sleigh” at Orway Hall on Washington Street in Boston, on September 15, 1857. Courtesy Harvard University, Houghton Library, Harvard Theatre Collection, American Minstrel Show Collection 1823–1947, (MS THR 556)

Hamill unearthed a story that is stranger than fiction: it proposes that one of America’s most popular seasonal melodies was penned by a peripatetic, perennially broke ne’er-do-well. He was the son of a New England abolitionist but shunned his father and enlisted in the Confederate army, and his virtuous wintry verses were first performed in blackface in a minstrel show. And no, Pierpont could not have written “Jingle Bells” in a Medford tavern in 1850, because in 1850, he was in California trying in vain to cash in on the Gold Rush. He did enjoy some small measure of success as a daguerreotype artist, at least until an 1851 San Francisco fire burned down his shop. He returned to Boston, broke.

“I don’t have the definite answer to where he sat down and wrote the song,” Hamill says. “But—and this is where my town is going to be mad at me—it was absolutely not written in 1850 at the Simpson Tavern in Medford.”

“This was the playbill,” she says, handing over a copy from the Harvard Theater Collection at Houghton Library that puts the song’s first performance at impresario John Ordway’s Ordway Hall, on Washington Street in Boston, on September 15, 1857. Then called “One Horse Open Sleigh,” it was performed by Johnny Pell, working with a troupe called Ordway’s Aeolians, who performed for half the show as “Dandy Darkies.” Ordway Hall, opposite the Old South Meeting House in Boston, was a hotspot for the then-popular entertainment of white men performing in blackface, offering a racist caricature of people of color as middle-class entertainment.

“One Horse Open Sleigh” was presented regularly that fall, one of about a dozen songs that Pierpont wrote for Ordway’s performers. It’s not known if the composer attended the debut performance, which was concurrent with his move to Savannah. Soon after, he copyrighted the song, and in 1859 he recopyrighted it as “Jingle Bells, or the One Horse Open Sleigh.”

An American Classic

Today, “Jingle Bells” is one of the most recognizable American melodies. It has been recorded thousands of times—by everyone from the Beatles to Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, and from Luciano Pavarotti to the Partridge Family to Pearl Jam. In December, mildly concerned that messing with the song’s backstory could ruffle some Medford feathers, Hamill presented her initial findings to the local historical society.

“It won’t change anything in the mind of the average Medfordian,” says John Anderson, president of the Historical Society & Museum. “People who care about the truth thought it was interesting, and people who don’t just ignored it.”

Over time, Hamill’s research into Pierpont’s story evolved from a volunteer project to serious research. It has taken her to the Morgan Library in New York—Pierpont was the uncle of J. P. Morgan—to read a collection of letters between Pierpont, his father, and other family members, and to the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah.

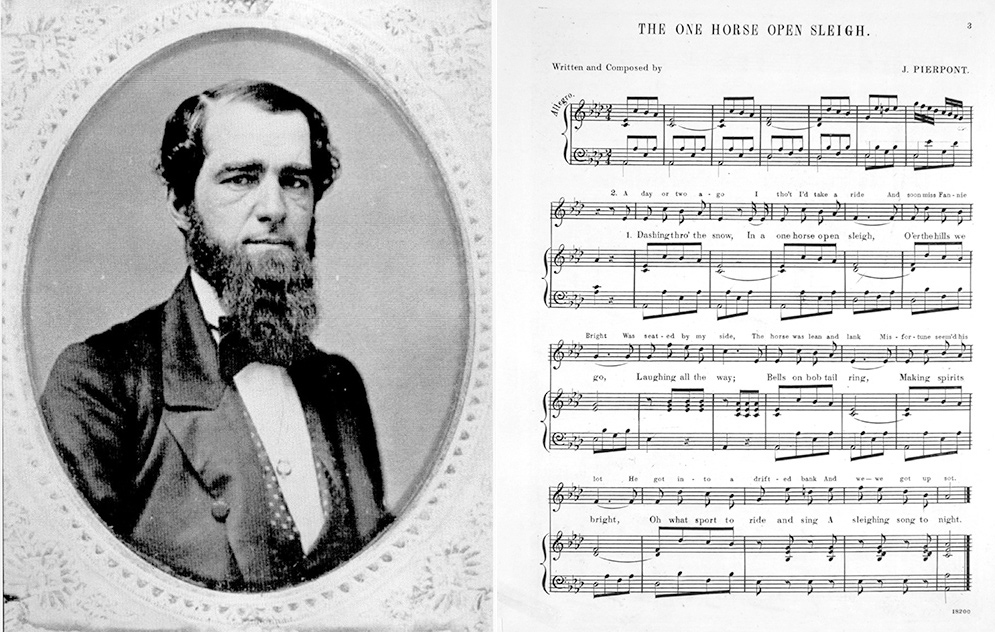

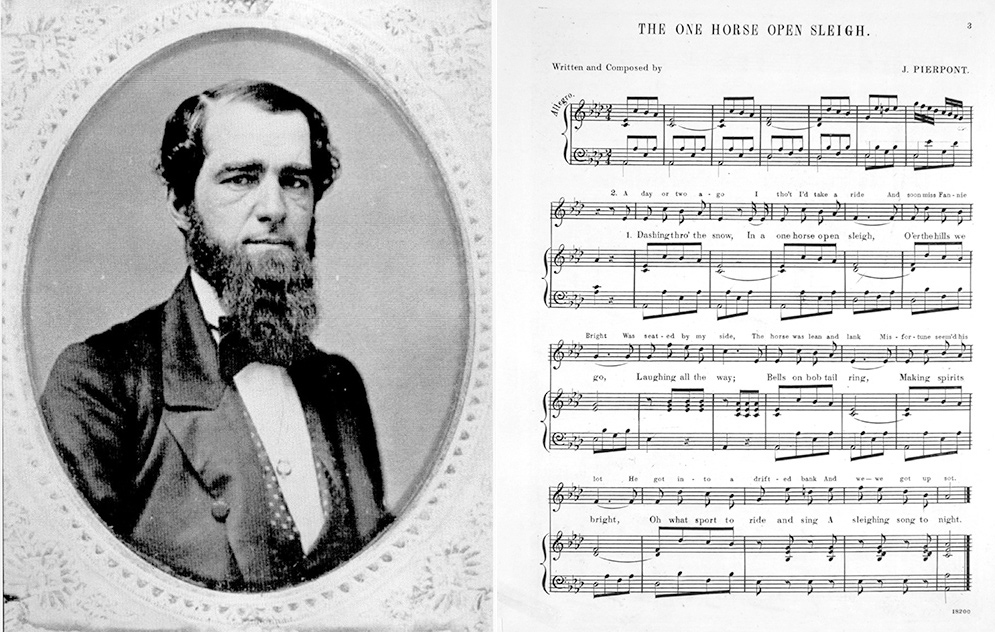

One of the only known photos of James Lord Pierpont (left). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. The opening bars of the original 1857 sheet music for “Jingle Bells” under its earliest title, “The One Horse Open Sleigh” (right). Courtesy Library of Congress.

She points out that James Pierpont was “a bit of a drinker, a bit of a wild guy,” who had a difficult relationship with his demanding father, Rev. John Pierpont, a famous abolitionist who accepted a pulpit in Medford in 1849. James Pierpont’s first song for Ordway’s performers, written in 1852, was “The Returned Californian,” a probably autobiographical ditty about a man who failed to find fortune on the West Coast and returned home. “I’m going far away from my creditors just now,” the lyric begins. “I ain’t the tin to pay ’em…”

Pierpont always needed money, says Hamill, so it doesn’t make sense that if “Jingle Bells” was written in 1850 and was well received, the starving writer would shelve it for seven years. It’s also unclear when the people of Medford started sleigh racing on Salem Street. The earliest photographic evidence dates to the 1870s. Sleigh racing and sleigh rides were common activities in the mid-1800s, giving young men and women a chance for fraternization and a bit of drinking. There were a number of popular minstrel songs involving sleighs, such as “The Merry Sleigh Ride” and “Buckley’s Sleighing Song,” and Hamill is not surprised that “Jingle Bells” bears more than a passing resemblance to them. That’s not to say “Jingle Bells” was plagiarized, says Hamill, but “Everything about the song is churned out and copied from other people and lines from other songs—there’s nothing original about it. He’s making money.”

So where and when did Pierpont write the song? Hamill says her best bet is a rooming house not far from the Old State House in downtown Boston, where he lived at least in the early summer of 1857. Pierpont’s wife had died the year before, and he basically abandoned his two children when he moved to Savannah, where he had previously played organ in his brother’s church. On his return, he tried several other jobs and fathered several more children with a second wife. He later joined the Confederacy in the Civil War, serving as a company clerk and penning fight songs to rouse the men in grey as they defended slavery on the battlefield. His father, meanwhile, served as a Union chaplain.

Johnny Pell appeared many times in blackface as part of Ordway’s Aeolians. Courtesy Harvard University, Houghton Library, Harvard Theatre Collection, HTC Photographs 3.528

“Jingle Bells” didn’t become a Christmas standard until decades after it was first performed on Washington Street. Some area choirs adopted it as part of their repertoire in the 1860s and 1870s, and it was featured in a variety of parlor-song and college anthologies in the 1880s. It was first recorded by the Edison Male Quartette in 1898 on an Edison cylinder and became a Christmas favorite in the early 20th century, often associated with a Currier & Ives image of pastoral Christmases past.

Hamill says the first assertion that the song was written in Medford appeared in a Boston Globe article in 1946. “It’s really a 20th century invention,” she says. “That’s very common with local history.”

Hamill is convinced that the plaque at 19 High Street is the product of bad information and/or wishful thinking. “Mrs. Otis Waterman,” named as a witness to the composition, is no longer around to ask.

Hamill is still digging. She plans to report her findings about the popularity of sleigh songs from 1853 to 1858, including “Jingle Bells,” in a peer-reviewed article in the journal Theatre Survey in 2017. In the meantime, Anderson says the plaque will stay where it is, because it’s still technically possible the song was written in town at some point. And the town will continue its annual Jingle Bell Walk/Run, which benefits Medford schools and features a 5K run and holiday tree display.

“Local history sticks,” Hamill says. “And once it’s connected to the identity of the town, it’s really hard to change.”

Who knew that Jingle Bells had a second verse? It’s almost as obscure as the other three verses to the Star Spangled Banner.