Nobel Prize–winning poet and playwright Derek Walcott (Hon.’93), who taught at BU from 1981 until he retired in 2007, died March 17, 2017, at his home on his native Saint Lucia, at age 87. No cause of death was given, but he had been in poor health.

“I am sad for BU and sad for the world,” says playwright Melinda Lopez (GRS’00), a College of Arts & Sciences adjunct assistant professor of playwriting, who was a student in Walcott’s playwriting class.

“For those of us who knew and loved him, Derek’s passing is a milestone in our lives—certainly it is in mine,” Boston Playwrights’ Theatre (BPT) artistic director Kate Snodgrass (GRS’90), a CAS professor of the practice of playwriting, wrote on the theater’s blog. Walcott founded the BPT in 1981. “For the world, we have lost a needed presence, a gifted poet and playwright, a true literary giant.”

Walcott won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992 for work the Nobel committee called “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.” At the time, his most recent work was 1990’s Omeros, a Caribbean epic the committee said was “a work of incomparable ambitiousness, in which Walcott weaves his many strands into a whole.”

In announcing the prize, the Nobel committee said, “In him West Indian culture has found its great poet. Three loyalties are central for him—the Caribbean, where he lives, the English language, and his African origin.”

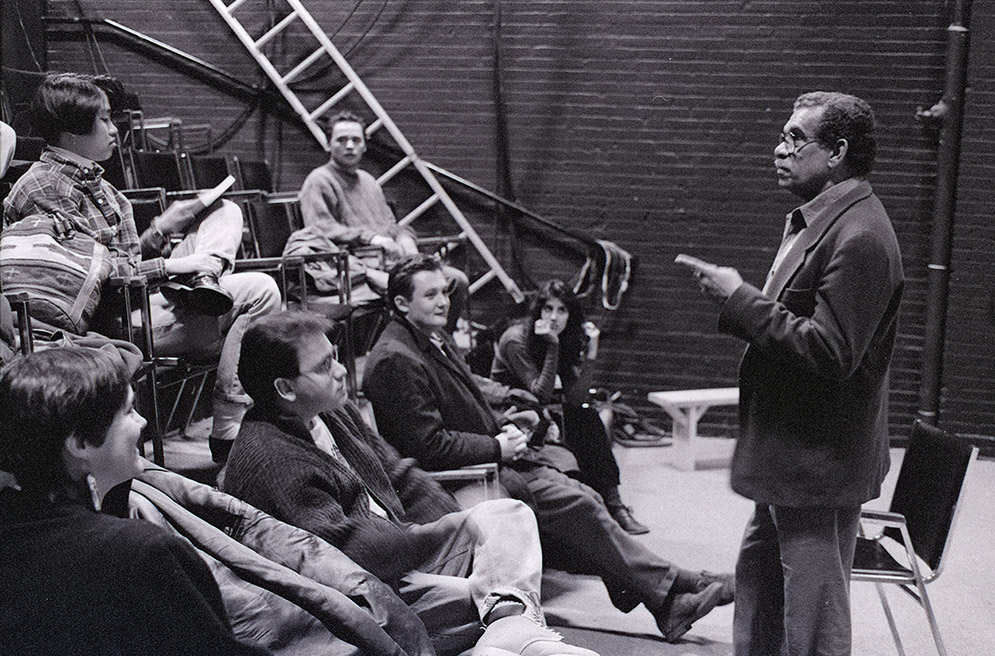

Walcott was teaching poetry and playwriting at BU in 1992, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Portrait: Photo by Tom Herde/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

In Boston, Walcott was perhaps best known for his work in theater. In 1981, the year he began teaching in the Creative Writing Program as a CAS professor of English, he won a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, commonly known as the “genius grant,” and he used a portion of his award to help found the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, still going strong today. His son, Peter, an architect, designed the first theater space in the rear at the Comm Ave facility, Snodgrass says. Walcott wanted playwrights and actors to have a place to grapple with new work, she says, and he loved working with actors.

“He wanted to bring poetry back to American theater; I don’t mean strict verse, but the rhythmic, musical language that Derek was so strong with,” she says. “He always wrote in verse, which is extraordinary and not done that often here. His work is Shakespearean in its language and also in its themes.”

Snodgrass says that Walcott’s playwriting “is humanist and complicated,” with themes of colonialism and society-against-the-individual, but also seen through flawed yet heroic characters.

“There is a certain sadness around his plays, a wistful longing,” she says. That may be why she names play-with-music The Joker of Seville, written with his friend Galt McDermot, composer of Hair, as a favorite: “There’s a great deal of joy in that, and humor.”

Lopez, author of Sonia Flew and Becoming Cuba, says Walcott was a “terrific and terrifying” teacher. In his class, student playwrights brought in scenes to be read by actors. “Sometimes Derek would let the scene go for a page, and sometimes he’d stop it after the first line,” she says. “He’d ask all sorts of questions about the first line, the first moment, what happened before the lights went on.

“I remember a classmate of mine who literally could not get through the first line, because they spent 20 minutes of class time discussing what happened before that speech,” she says. “I watched my classmates just squirm and squirm, all of them wondering where this was going, and then there was the ‘aha moment,’ where we all got his point, which is that the play starts before anyone speaks. Derek didn’t explain—he did. And waited for us to catch up. And that could be terrifying if it was you. But he was right.”

Lopez recalls that in 2009 Walcott was visiting Boston and came to see a production of her play From Orchids to Octopi at the Central Square Theater in Cambridge. “He was lovely and gracious,” she says, “and then he said to me about the play, ‘That was a lot of words.’ That was so Derek, because it was absolutely spot-on, a very good critique that I would learn from, and it had his devilish humor.”

His approach to poetry class was similar. “Derek didn’t use class time for workshopping student poems,” says poet Kirun Kapur (GRS’00), who recently published the collection Visiting Indira Gandhi’s Palmist (Elixir Press, 2015). “If you wanted to talk about something you’d written, you had to go and see him in his office, which felt a bit like visiting the lion in his den. You had to screw up your courage. He knew this and relished it, I think. The writing of poetry was a brutally serious undertaking to him—something requiring plenty of courage. I was lucky enough to have many extraordinary conversations with him in his office. We were both from islands, and he never got tired of talking about the sea.”

Lopez and Snodgrass remember how Walcott loved getting Chinese takeout food after class at the now-gone Chef Chang’s. “We’d have these fabulous meals with this Nobel laureate and tell jokes and talk literature,” Lopez says. “It was quite an extraordinary event to be in the room with him.”

Lopez says she came to know Walcott best, in a strange way, when she studied his work in a poetry class with Anita Patterson, a CAS professor of English. “His poetry is beautiful and complicated,” she says. “I can return to it over and over again.”

Born in 1930 on the island of Saint Lucia in the West Indies, Walcott published his first poems as a teenager. He taught school at various places around the Caribbean after graduating from the University College of the West Indies in Jamaica. The first of his collections to catch the attention of critics was In a Green Night, published in 1962. Among his friends and supporters over the years were Robert Lowell (Hon.’77), Joseph Brodsky, and Seamus Heaney, the latter two also Nobel laureates. Walcott was also a talented painter, and his watercolors of Caribbean scenes sometimes appeared on his book covers.

His first play was produced in 1950, and he founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop (then called the Little Carib Theatre Workshop) in 1959. The troupe performed two of his plays at the Boston University Theatre in 1995, the Elliot Norton Award–winning The Joker of Seville and the Obie winner Dream on Monkey Mountain. Walcott hit Broadway in 1998, with The Capeman, a collaboration with Paul Simon.

Related Stories

Do Your Future Work with Passion, Nobel Laureate Tells Graduating University Seniors

Climate change scientist Mario Molina (Hon.’17) delivers Baccalaureate Address

Former Poet Laureate Pinsky Designs Anthology for Aspiring Poets

CAS prof’s book offers “ways to learn from the poetry of the past”

BU Playwrights Triumph at Kennedy Center Festival

Awards for best comedy, ten-minute play

Post Your Comment