Issue Archives

Bostonia is published in print three times a year and updated weekly on the web.

Summer 2018

Winter-Spring 2018

Fall 2017

Summer 2017

Winter-Spring 2017

Fall 2016

Summer 2016

Winter-Spring 2016

Fall 2015

Summer 2015

Winter-Spring 2015

Fall 2014

Summer 2014

Winter-Spring 2014

Fall 2013

Summer 2013

Winter-Spring 2013

Campaign 2012

Summer 2012

Winter-Spring 2012

Fall 2011

Summer 2011

Winter-Spring 2011

Fall 2010

Summer 2010

Winter-Spring 2010

Fall 2009

Summer 2009

Spring 2009

Winter 2009

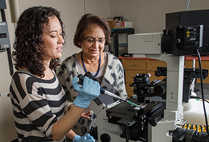

My name is Patricia Oduba (nee Mallory). I just read the article by Ashley Farmer. I was made aware of the article by my lawyer, Rene Myatt, who ran across the article. She is a graduate of Boston University.

Ms. Myatt was not aware of my mother’s history until she read the article. What a series of coincidences. Hidden histories of African heritage women are coming to light.

As Ms. Farmer indicates, and many in the USA are noting, that the movement was supported in numerous life changing ways, by African heritage women by our votes, money, and presence made all the difference

Hi Pat this is Jackie Edwards the one with the six children please respond to this email I have been trying to get in touch with you. I am so happy to see your mom’s life celebrated