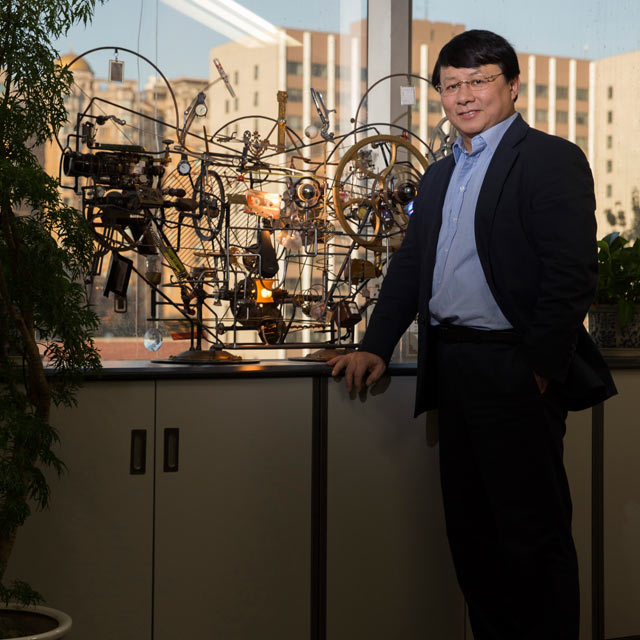

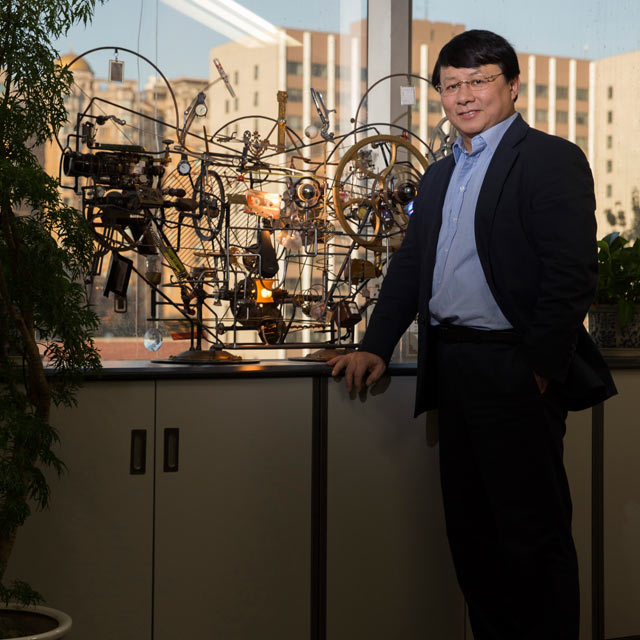

Financial analyst Guanlei Ren returned to China in 2009, when the US economy was sinking and China’s was booming. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

Wenwen Wang and Guanlei Ren have several reasons to consider themselves fortunate. For one thing, they are sitting in a booth at the China Grill restaurant on the 66th floor of Beijing’s upscale Yintai Center, and the evening sky is so uncharacteristically clear that they are able to watch the sun set behind a sparkling palisade of modernist skyscrapers.

For another, Wang (COM’08) and Ren (GRS’07, COM’09) have a plan

to start their own business—a video

production company—that could provide a good living shaped largely by

their dreams.

But mainly, Wang and Ren are fortunate because they live in China at a pivotal time in the country’s history. Like most young professionals working in Beijing, they believe that after a century of struggling to make and remake itself, China is approaching its moment. Wang and Ren are thrilled and honored to be part of it.

Returnees contribute disproportionately to the economy, accounting for 81 percent of the members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Their lives are different from those of previous generations of Chinese and different too from the lives of most Americans. They are defined by their duties as only children, and enabled by the first-generation wealth of their parents. They are unequivocally global.

The two hopeful entrepreneurs acquired their skills in video production nearly 7,000 miles from Beijing, at Boston University. The clients they will work for, the young women imagine, could be from anywhere in China. And the videos they hope to create could be seen by people anywhere in the world. That international progression, learning in the United States, building in China, and sending product out into the world, is for many young Chinese an increasingly common skip and jump to a whole new lifestyle, and it is changing all three stations along the way: American universities, China, and the world.

The Decision Nick Haisu Yuan (CAS’14, COM’14) talks about the decision that every Chinese student faces: whether to stay in America or return to China after graduation. Video by Devin HahnDownload Video

Huiyao Wang, a Beijing-based expert on foreign-educated Chinese, says the several ways that the trend has changed China are overwhelmingly good for China. His research shows that returnees, people who were educated overseas, contribute disproportionately to the Chinese economy, accounting for 78 percent of Chinese university presidents, 72 percent of senior positions at the leading state and provincial research centers, 81 percent of the members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and 54 percent of the members of the Chinese Academy of Engineering. He points out that returnees have founded several Chinese internet giants, including Baidu and Sohu, as well as the first venture capital firm, IDG Capital Partners, started by BU trustee Hugo Shong (COM’87, GRS’90).

“People who are educated overseas bring new thinking that will influence all aspects of society, culturally, socially, and politically,” says Wang, who is director general of the nonprofit Center for China & Globalization and vice chairman of the China Western Returned Scholars Association, as well as a senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “They bring new ideas and new technology, and they bring new business like venture capital. All of those things are helping China become more international, and international connections are very important.”

At the moment, Wenwen Wang and Ren have an ambitious plan, but few assets. They don’t own their own video camera—they rent one—and they don’t have a workspace, mainly because all space in Beijing comes with a prohibitively high price tag. What they do have is a set of attributes that Huiyao Wang says puts them on a fast track to success: English language skills, professional training from a highly regarded university, and a conviction—uncommon in their parents’ generation—that they really can shape their careers to fit their dreams.

Wenwen Wang is a reporter for the Global Times, a daily paper that publishes in Chinese and English. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

They also have day jobs that, by the standards of any city in any country, are rewarding. Wang is a reporter for the Global Times, a daily newspaper that publishes in both Chinese and English, and Ren is an analyst in the investment banking department of Zhong De Securities, a joint venture of Shanxi Securities and Deutsche Bank.

On most days, Ren works in a high-rise office in the central business district of Beijing, a city whose main tourist attraction, the Forbidden City, has been overshadowed by starchitect skyscrapers that sit cheek by jowl with gray concrete Sino-Sov housing projects. Living in this chaotic, exuberant city with

20 million people, projected to grow to 25 million by 2020, it’s easy to believe that one is at the center of the world.

Ren remembers the rush of optimism she felt returning to China in July 2009, a time when the United States was still discovering the true depths of its financial crisis. “I felt very excited,” she says. “I thought I had a very good

opportunity to learn the capital market of China and might be able to contribute to the development of the society. I felt that I was one of the people who were

in the big time, and I did my job with great enthusiasm.”

Almost five years later, although the growth rate of China’s gross domestic product has backed off the 8 percent a year that it had reached for a decade, Ren’s enthusiasm hasn’t diminished, and neither has the intensity of her daily routine. Much of her time is spent doing due diligence for clients seeking regulatory permission to conduct mergers, acquisitions, or IPOs, three business practices that until recently were considered exotic. And much of her time, two-thirds last year, in fact, is spent traveling to companies hoping to go public, to buy other companies, or to be bought themselves. The pace, she says, is relentless, and relentlessly exciting.

Much of Ren’s time is spent traveling to companies that hope to go public, buy other companies, or be bought themselves. The pace, she says, is relentless, and relentlessly exciting. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

“It doesn’t matter if I’m in Beijing or some other place,” she says. “We usually have to work overtime. When there are rush deals, we have no free time.”

Ren says her downtime in Beijing is a lot like her downtime was in Boston: she goes to the movies, she goes out to eat with friends, and she tries to find time to get to the gym. But there are differences here. The number of cars on city streets makes getting from point A to point B maddeningly time-consuming, and often not worth the effort. Passengers routinely leave stationary taxicabs and walk to their destinations, and the air is so polluted that even those people lucky enough to win a license plate in a complicated lottery system are often prohibited from driving on designated days of the week.

Perhaps the biggest difference between life here and back at BU, says Ren, is cultural: Chinese custom demands that young adults spend more time with their parents than her American classmates at BU would think reasonable. “Life in the United States was much simpler,” she says.

The Path Back to China

For Jeff Zhao, visiting with his parents is not a problem. Zhao (SMG’11) lives with them, primarily because of exorbitant Beijing rents. Like Ren, he works as a financial analyst in Beijing’s central business district, and he travels often to meet with clients of his employer, the China International Capital Corporation. In most cases, Zhao says, he is scouting for start-up companies to invest in. He specializes in what he calls “the food space,” and he is pleased with a recent investment in a young company that produces organic milk, the kind of promising boutique product that would have died on Beijing store shelves a few years ago.

Zhao’s English is flawless, surprisingly so until he explains that he spent his early years, through kindergarten in fact, in the United States while his parents went to graduate school. When his family returned to China, he was sent to the International School of Beijing, in Shunyi, a former US embassy school. At BU’s School of Management, Zhao studied finance and accounting, and when he graduated he sensibly chose to work, he says, where the GDP was thriving.

A Day in the Life

Jeff Zhao (SMG’11) investment banking analyst

Read More

7:30 a.m.

Wake up, check BlackBerry. Have breakfast of muesli, yogurt, eggs, or Chinese congee, with either a “café,” or a double espresso macchiato made in my espresso machine. I brought back organic beans from the United States, which are cheaper than you find in China.

9:15–11:30 a.m.

Roll into office, tend to outstanding work. Usually around this time my conference calls for various projects begin. If the call is not due diligence–related, I multitask and work in the background.

11:30 a.m.–noon

Associate vice president calls me to go over a return/leveraged buyout model that I set up. He questions some of my assumptions and tells me to further break down the target company’s operating expenses and other financial metrics.

noon–1 p.m.

Go out to lunch with friends. Lunch really depends, because there’s a lot of variety. I stay away from mainstream restaurants, given the lack of quality procurement (gutter oil, terrible-quality meat, MSG, you name it). So I go to either a dumpling house, a bakery, the salad bar at the JW Marriott outside my office, or this Korean lunch place called Bibigo.

1–1:30 p.m.

Back on the phone, this time with advisory firm to confirm travel plans for tomorrow. We are working on a potential investment together and need to do on-site due diligence.

1:30–3:30 p.m.

Principal tells me he is visiting another company tomorrow and asks me to do some research on the industry and tailor our company introduction materials to them. I do it quickly; as a rule we don’t spend a lot of time on a company until we know there is a deal.

3:30–5:30 p.m.

I have a conference call on a niche industry with industry experts. Companies with networks of experts like to arrange experts in various industries to talk with us so they can sell us their expert consulting services. I listen in. I’m interested, but while I’m on the phone I continue to work on my modeling.

5:30–6:30 p.m.

I talk to my associate VP about my model again and go over points of focus for tomorrow, when we go to see the company together. I usually clock out around 7, then head to the gym, where I follow The 4-Hour Body program by Timothy Ferriss, and occasionally have a boxing lesson.

6:30–7:30 p.m.

Do a little bit more work at home, preparing for tomorrow’s flight to visit with officials of a young company.

“Prospects for China were promising,” he says. “GDP growth was triple or quadruple that of countries in the developed world. There was a lot of investment banking activity, especially with regard to the privatization and public listings of Chinese state-owned enterprises, and there were plans by Chinese securities regulators to allow foreign multinational companies to come and float their shares in the Shanghai Stock Exchange. And given the shortage of truly bilingual talent, especially at the junior level, I saw a good opportunity for myself.”

Global Ripples

Aimin Yan, an SMG professor of organizational behavior and faculty director of the school’s International MBA Program, says returnees like Zhao also represent a good opportunity for China. Yan, who spends three months each year in China and meets often with BU alums in senior management positions, estimates that the country will need

between 30 million and 50 million managers at different organizational levels in the next 10 years. He thinks as many as half of them will be educated in the West.

“I haven’t done a real study about the globalization of Chinese companies,” says Yan, “but I can hypothesize that more than 80 percent of country managers of Chinese multinational companies have a Western education.” That, he says, leads to a global ripple effect that is increasingly significant, as Chinese trade with other countries swells. (China’s direct investment in Africa increased more than 20 percent a year from 2009 to 2012, to $2.52 billion, according to China’s State Council Information Office, and the UN Conference on Trade and Development reports that China’s direct investment in Latin America increased from $621 million in 2001 to $44 billion in 2010.)

Returnee expert Huiyao Wang believes the migration to universities abroad is a major force behind China’s 30-year climb to its current position as the world’s second largest economy, in terms of both gross national product and purchasing power. His research shows that recent returnees, unlike their predecessors, tend to be entrepreneurs, and very often high-tech entrepreneurs. He says Zhongguancun, a part of Beijing that is known as China’s Silicon Valley, employs more than 9,800 returnees.

Vincent Fenghua Wang, an executive manager at the Shanghai Stock Exchange, sees another difference between earlier and more recent returnees.

“The earlier stage of globalization was more on a production level,” says Wang (GRS’02). “Now it has reached the thinking level. At this level, the returnees’ impact is more subtle but also much more profound. They help people in China understand America and provide a map of interpreting global events. The result is a positive impact on every aspect of life, as the United States may become an economic, political, and probably even philosophical reference for China. I believe it will make the world a better place.”

Jay Kim, an SMG associate professor of operations and technology management, has been leading graduate seminars in China since 1994. He says SMG grads who return to China generally take one of two paths. “I see alums who create small companies,” says Kim, who meets frequently with alums in China. “They are often in high-tech or web-related fields, and that is very important for China’s development. They bring to Beijing some colors and smells that weren’t there, and when there are enough of them you have a subculture that will play an important role in the future development.”

Kim says the second commonly followed career path leads to management at multinational companies. “China has a lot of multinational companies, and they find it difficult to develop a coherent strategy,” he says. “They don’t have sophisticated midlevel managers, which is exactly what our MBA graduates are. They are ideal candidates, and China has a shortage of them.”

Jeff Zhao believes that he brings his employer three important skills: salesmanship, financial analysis, and familiarity with two influential cultures, Chinese and American. “Salesmanship is something that can be learned on the job,” he says. “You can also learn it through practice, as I did at BU. My understanding of financial analysis can be partly attributed to BU, but much of it is self-taught. My familiarity with Chinese and Western culture comes from living in China and going to international schools, as well as going to BU.”

He also believes that the deals he influences every day make a positive contribution to Chinese society, and that’s important to him. “While we are focused on generating returns for our investors, our multicultural and multiregional background and coverage puts us in a unique position to make deals happen across borders,” Zhao says. “That happens when a Chinese company is looking to acquire foreign technology abroad but lacks the negotiation skills to do it. We come in and help them. The Chinese company gains technology, which they can apply to the China market. Everyone wins.”

Zhao meets former BU classmate Fred Dafu Lu at a hot pot restaurant on the sixth floor of Shinkong Place, a Beijing luxury mall that advertises “938 brands from around the world.” Zhao and Lu (SMG’11) have much in common: both speak unaccented English, both attended the embassy school in Beijing as well as SMG, and both have parents whose education condemned them to years of farm labor during the Cultural Revolution. During that 10-year period, from 1966 to 1976, Chinese universities were shuttered and the country ceased sending students abroad. Today, Huiyao Wang says the practice, instituted by Mao Zedong, cost the country a generation of economic progress and set back its development by decades. Lu mentions that his mother has fond memories of her temporary life in the country. Zhao doesn’t think so: the stories passed down in his family were of a different kind.

Lu studies the menu. It’s expensive, but not surprisingly so. This is a popular restaurant in a Western-style mall in the central business district of Beijing. And while by US standards most Chinese salaries are unimpressive (the average annual income in Beijing, which has the highest income in China, was just shy of $8,000 in 2012), there is money to be spent. On Singles Day, the Black Friday and Cyber Monday of China, last year, Taobao and Tmall (China’s Amazon and eBay) sold more than $5.7 billion in merchandise, two and a half times what American retailers sold on Cyber Monday.

Fred Dafu Lu works in Hangzhou, China, for a US-based developer of mobile apps. His cousin, who studies at UC Irvine, hopes to find a research job in the United States. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

The meal starts with cold beer, a plate strewn with duck innards, and a recap of Lu’s fledgling career. He works in Hangzhou, in Zhejiang province in eastern China, as a kind of chief operating officer for a San Francisco–based internet start-up that develops social mobile applications for iOS and Android platforms. The company’s flagship product allows users to send text messages, voice messages, photos, videos, location, contact information, and other information over data networks. It is, to some extent, inspired by Weibo, the web-based communication tool that is the standard among young Chinese, at home and at BU. Lu knows that Weibo, with roughly the same market penetration in China that Twitter has in the United States, is unassailable on its home turf, but he thinks young people in other countries, including the United States, might adopt a tool with texting-like capabilities but no data charges. It’s the skip and jump that, according to Huiyao Wang, is sparking much of China’s economic development: schooling abroad, working at home, marketing to the world.

“China is transitioning from a source of cheap labor and manufacturing to a more globalized marketplace,” says Lu, who wants to be part of that change. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

Lu says he’s encouraged by the number of internet companies that are disrupting traditional industries, dominated by state-owned enterprises such as communications, financial services, and education. “I wanted to be part of the change,” he says. “China is transitioning from a source of cheap labor and manufacturing to a more globalized marketplace, and I wanted to help shape the course of change as much as I can to a place that is more efficient, transparent, and globalized. Social and environmental issues aside, I’m seeing more and more of my friends and acquaintances who live abroad move to China to take advantage of the potential possibilities in almost every industry.”

Archaeologist Jing Wang says China’s rich culture is the country’s soul. Photo by Gilles Sabrie

That said, Lu cites the example of a cousin studying stem cells at the University of California at Irvine who has decided to look for a job in the United States, where research facilities are better equipped than they are in China. Others who have studied in the United States and decided to stay express concerns about air pollution in China. One young graduate of Cornell said she returned to Beijing after graduation intending to make her career in management in China. After one year of breathing the air, she said, health concerns compelled her to take a job in California.

Lu believes that SMG prepared him well for such a global enterprise. “Aside from the basic business skills you learn from the required curriculum, working in a group of students with different concentrations and cultural backgrounds definitely helped me,” he says. “The international community makes up a pretty significant portion of students in SMG.”

Contemplating China’s Soul

When Jing Wang (CAS’08) talks about acquisitions, she’s not referring to the mergers and acquisitions that concern her fellow alums; she’s talking about procuring artifacts that document China’s 8,000 years of civilization. The young archaeologist, who works for

China’s National Conservation Center for Underwater Cultural Heritage, spends most of her days collecting materials, reading, thinking, and writing articles or project reports. Wang, upbeat and scholarly, says she prefers to work in the field, where she plans excavations, makes drawings, and catalogs artifacts. And she believes that her work is every bit as critical to China’s future as the work of financial analysts and internet start-ups.

For example, Wang says, she recently finished a long project that considered whether China should approve the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, an issue that is particularly important to the future of China because it involves work done in international waters and seabeds.

Wang says she was fortunate at BU to have as her master’s thesis advisor a PhD student trained by K. C. Chang, a professor of archaeology at Harvard and one of the foremost authorities on ancient China. “K. C. Chang is my model,” she says. “I hope to do something important for archaeology in China. I hope that working in cultural heritage conservation will help China keep its culture, because that is the country’s soul, and in that sense it’s also important for the economy.”

Perhaps more than most returnees, Wang really does contemplate her country’s soul, thousands of years deep and rich in poetry, music, and other arts. And when she tries to reconcile the wisdom of the distant civilizations she studies by day with the world she sees on her way home—the skyscrapers and street vendors and the bicycles and new

Mercedes-Benz dealerships—she is blessed, she says, with a very long view.

“Beijing always impresses me with so many different people, ideas, and values,” she says. “It mixes the coolest issues in China with the most traditional issues. But it’s important to remember that Beijing changes more quickly than people do.”

The Producer

Hugo Shong figured that if it worked in America, it should work better in the world’s fastest growing economy

Hugo Shong has cut an unusual path to success in the new China. While he has made profitable investments in internet companies, he focuses on softer markets: publishing and entertainment. Photo by Adam Dean

Hugo Shong scrawls a number on a whiteboard in a conference room of the sixth-floor offices of IDG Capital Partners in the Dongcheng District of Beijing.

“Three hundred million,” he says. “That’s how many people are in the United States.”

He writes again.

“About 40,000,” he says. “That’s how many movie screens

are in the United States, OK?”

Shong (COM’87, GRS’90) pauses a moment for emphasis, then

raises his blue marker to the

whiteboard.

“So in China there are 1.3 billion people, and we have 16,000 screens by 2012.”

The message is that China, for all of its explosive commercial development, is still tens of thousands of theaters shy of its optimum number. The message says opportunity.

Shong, founding general partner of IDG Capital Partners and chairman of IDG Greater China, as well as a BU trustee, has been sounding out opportunities for two decades, and most of them involve the application of an American business model to the world’s fastest growing economy. In the early 1990s, Shong started publishing a Chinese edition of a technology magazine that had been produced for years in the United States. In 1993, he launched the first venture capital firm in China. Next came big-brand consumer magazines, a television game show, then movies, an outdoor concert venue modeled on Tanglewood, and most recently, Broadway-style theater.

Shong recently sent a team to New York to study the production of Broadway musicals. Photo by Adam Dean

Shong, who according to China Daily is known as “the godfather of Chinese venture capital,” has cut a broad and somewhat unusual path to success in the new China. Huiyao Wang, director general of the Center for China & Globalization, a nonprofit think tank based in Beijing, says most entrepreneurial “returnees”—Chinese who were educated abroad—put their Western education to work building technology companies. And while Shong has made many profitable investments in internet companies, his daily efforts often focus on softer markets: publishing and entertainment.

He now publishes more than 40 magazines, most with American titles, including Cosmopolitan, Harper’s Bazaar, National Geographic, and Men’s Health, and his IDG China fund has invested in nearly 300 companies, including Chinese internet behemoths like Baidu, Sohu, Tencent, and SouFun. In May 2012, China Daily put the value of his venture capital fund at $3.8 billion, which happens to be 100 million times what Shong says he had when he arrived at BU’s College of Communication in 1986.

Like most Chinese people older than 50, Shong felt the burden imposed by the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong’s dictate that from 1966 to 1976 forced “bourgeois” elements who he thought posed a threat to Communism to be reeducated by working as laborers on farms and in factories. As a young man, Shong spent four years working as an electrician in a factory.

“I made the equivalent of $6 a month,” he says. “Life was different because of the Cultural Revolution. We didn’t have the chance for a normal education. That’s why we appreciate the opportunity and why we always try to have some kind of dream.”

When the Cultural Revolution came to an end in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping, then China’s leader, championed broad economic reforms, including the opportunity to get a college education.

Shong was ready to go. “My happiest memory was in college,” he told China Daily. “I could take classes and learn new things every day. I always thought, isn’t that the most wonderful thing in the world.”

Shong graduated from Hunan University and took graduate courses in journalism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, where he won a scholarship to COM.

$38 and a Dream

He arrived in Boston, he says, with $38 and a dream of being the best journalist in China. He finished what was supposed to be a two-year program in eight months, and in 1988 enrolled in the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, where a professor helped him get an internship at Cahners, a publisher of trade magazines such as Variety and Publishers Weekly. “On the first day, I helped them negotiate a contract to publish four issues of Electronic Business in China,” Shong recalls. “They offered me a job.”

Shong attributes much of his success to two things: an ability to recognize opportunities and a willingness to seize them. When the Fletcher School was seeking a corporate sponsor for a dinner whose special guest was a Chinese business leader, he persuaded Cahners to pitch in.

At the dinner, the sociable Shong hit it off with another publisher of trade magazines, Patrick

McGovern, the founder and chairman of International Data Group (IDG). Three years later, when Cahners rejected Shong’s proposal to publish

another magazine in China, he rewrote the business plan around Network World, one of McGovern’s magazines.

“I had worked at Cahners 16 hours a day for 3 years,” says Shong. “I learned so much about the publishing business. But what I really learned about was venture capitalism and entrepreneurship. And I thought that China was an opportunity.”

McGovern read Shong’s proposal and invited him to a meeting that Shong recalls as an intense and interesting three-hour discussion. Finally, McGovern asked a question: if he were to fund Shong’s plan, how much would he expect to be paid? Shong told him $42,000, the same salary he was getting at Cahners. He also asked that he report directly to McGovern. McGovern had a slightly different idea. He offered Shong $50,000, to be reconsidered

in six months, when he had a better idea of what Shong’s efforts were worth. Half a year later, the two met again.

“I said, ‘Pat, what do you think?’” recalls Shong. “‘Have I met your expectations?’ He said, ‘Hugo, you have exceeded all of my expectations.’ And he doubled my salary.”

In 1992, Shong brought another, and much bolder, idea to McGovern: he wanted to start a venture capital fund in China. “Everything I knew about venture capital I learned from being a reporter and writing about it,” he says. “I really didn’t know much, but I knew people who did, so I talked to people at venture capital firms, such as Hambrecht & Quist and Schroder Ventures.”

Now a believer, McGovern gave Shong $10 million in seed money, and he was given another $10 million by the government of Shanghai.

“I learned a lot from Pat McGovern,” he says. “He had a philosophy of ‘Let’s try it.’ I learned

to identify opportunities, and he was willing to bet on me.”

McGovern’s bets paid off. Shong’s fund directed investment to several internet start-ups, including Baidu, Tencent (QQ), Sohu, Ctrip, and SouFun, companies that today are among the most successful in China. More than 70 of the companies fueled by Shong’s money have gone public or sold for high returns in the last 20 years.

“Hugo made investments in virtually every one of the highly successful technology-based companies starting in China during the 1990s,” says McGovern. “Under his leadership, IDG Technology Venture Investment averaged 800 percent growth on its investments. Hugo and his general partners now manage $4.4 billion of investment funds

in China, and they continue to get outstanding results.”

Shong attributes much of his success to two things: an ability to recognize opportunities and a willingness to seize them. Photo by Adam Dean

Shong and McGovern, whose initial magazines focused on technology and business, expanded their Chinese publishing to include consumer magazines, which flourished in China even while they flagged in the United States. The September 2013 issue of Cosmopolitan had more than 600 pages of editorial content and ads, and Harper’s Bazaar was so fat that it had to be printed in two parts. Shong says Men’s Health and National Geographic are also thriving, as American advertisers rush to get their products in front of China’s increasingly prosperous and brand-conscious consumers.

“Hugo grew IDG’s media business from 2 publications in 1990 to over 40 joint-venture magazines, newspapers, and websites today,” says McGovern. “Those include all the leading consumer magazines on fashion, jewelry, automobiles, travel. Hugo also has arranged to establish three centers for neuroscience studies at leading universities in China with philanthropic funding support of over $30 million.”

No Entertainment Stone Unturned

Movies were next on Shong’s list, and with good reason. The New York Times reports that China’s domestic box office was expected to hit $3.5 billion in 2013, making it the world’s second largest, behind the United States. Shong, whose IDG Media Fund has invested in several films, among them last year’s 21 & Over, says American filmmakers are “very good at making movies, but really poor at capturing culture.” He says there are many classic Chinese stories that could and should be made into movies.

“I know people in Hollywood,” he says. “And I see the potential to train American students to make movies in China.”

Toward that end, Shong last year funded a scholarship program that will send nine fellows of the American Film Institute (AFI) to China for cultural research that will support feature-length screenplays. The AFI/IDG China Story Fellowship gives the screenwriters a full scholarship to a second year at the AFI Conservatory, where they can develop their projects.

Shong says too many Americans know Chinese culture through Kung Fu Panda and Mulan. Photo by Adam Dean

“Too many Americans know Chinese culture through Kung Fu Panda and Mulan,” says Shong. “But China has a remarkable and distinguished history. Americans deserve to see other types of movies about China, movies that can educate them and touch their hearts.”

Three years ago, Shong also founded Looking Beijing, a partnership program between Beijing Normal University (BNU) and IDG that sends eight Boston University film majors to Beijing for 10 days each summer. There they are paired with a communications major at BNU and set loose in the city to film short documentaries on subjects they choose.

“The US students take the lead in the creative part, and the Chinese students are producers,” says program coordinator Roni Zhang (COM’08). “The BU and Chinese students work one-on-one, so it’s not just about making a movie in the end. The process of making the movie itself is interesting.”

In 2006, Shong became the face of Chinese entrepreneurship, literally, when he signed on as one of three leading judges on the popular television show Win in China, which gave $5 million in venture capital funding to the contestant with the most viable business plan. The show attracted tens of millions of viewers, who shared on social media Shong’s often-witty remarks.

Shong sometimes seems unwilling to leave any entertainment stone unturned. Since 2010, his IDG Media Fund has been organizing the annual Beijing Great Wall Forest Festival in the Music Valley, an outdoor concert venue next to the Great Wall that is modeled on the Tanglewood Music Festival in Lenox, Mass. He plans to expand the park, one hour from Beijing, to include indoor and outdoor theaters, hotels, and villas.

In April 2013, true to his formula of translating American know-how to Chinese business, Shong sent a team from his media fund to New York to meet with the Nederlander Organization, which owns nine Broadway theaters and is known around the world for its production expertise. Shong says he hopes to produce in China “the kind of beautiful musicals” seen in New York theaters.

“What China has now is a huge market,” he says. “What the United States has is a place to learn. It has the best education system, and it has competitiveness. I think that over the next 20 years, the two countries will make a big difference in the world, socially, culturally, as well as economically.”