![]()

Departments

Arts

![]()

|

Week of 25 September 1998 |

Vol. II, No. 7 |

Arts

SFA prof sets the record straight on his G-man father

|

|

|

Collage, 1994

|

At work on a book about the FBI's investigation of John Dillinger, one of the most sought- after violent criminals of 1930s, Alston Purvis says he's had the benefit of a tireless research assistant: longtime FBI head J. Edgar Hoover.

Purvis' father, Melvin, was the special agent in charge of the FBI's Chicago office from 1927 until 1935. He was one of the agents shooting in the alley outside of the movie theater the night Dillinger was shot and killed.

"I have most of the papers right here," says Purvis, gesturing to a row of thick blue binders on his bookshelf. Those papers include correspondence between Hoover and Purvis' father. The salutations are at first formal, but by 1935 Hoover addresses him more cordially -- "Dear Melvin" and finally "Dear Mel."

"I can tell you where my father was and what he was doing on any given day during that period," he says. Purvis' collection of documents is evidence of the extreme thoroughness that characterized Hoover's inquiries. Director of the FBI from 1924 through 1972, he was notorious for obsessively and illegally collecting data on employees and enemies, real or perceived. During his administration, the public had the sense that Hoover had the power to investigate even the most private details of the life of whomever he wanted. Hoover's records concerning individuals' whereabouts evoked fear in the '30s, but today they bring a smile to Purvis' face. "Hoover did a lot of the work for me," he says.

Forthcoming this year, his book explores the relationship between his father and Hoover. His book criticizes the director but not the FBI, which Purvis says his father believed in and served loyally. "Hoover's love of absolute power is vividly demonstrated by the fact that there are files kept on Daddy, even after his death," Purvis says.

Some sources record Melvin's death as a suicide. Purvis' examination of the relationship between Hoover and his father questions that pronouncement.

Purvis, director ad interim of the Visual Arts Division at SFA and chairman of the graphic design department, is disappointed that his father has been misrepresented by the sloppiness of other authors and by Hollywood. "Even on projects I've contributed to," he says, "they haven't been precise. I'm glad that interest in my father is being rekindled and I think Hoover's racket is becoming more well-known. I'm being very meticulous in my research. I just want to write the thing and put the matter to bed."

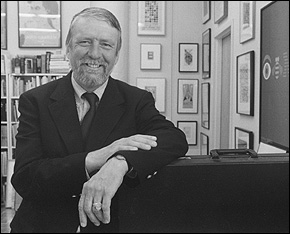

Alston Purvis, director ad

interim of SFA's Visual Arts Division.

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

That's an understandable sentiment when viewed

in the context of Purvis' busy life. Between writing his

book and attending to his administrative responsibilities as

chairman, Purvis finds time to teach, paint, and work in

collage and freelance graphic design. He is also married,

with a young son.

Born in Charleston, S.C., Purvis spent his boyhood surrounded by extended family. "I was greatly influenced by my mother and aunts," he says. "It's true for many Southern families -- there are a lot of intelligent, nurturing women whose men were killed in the war. They were asked to carry a lot, and have developed the means to do so." Some of his fondest memories, he says, are of sitting on his porch listening to the women in his family tell stories.

The art that Purvis creates is another reflection of the supportive environment in which he grew up. He recalls his father encouraging him to acknowledge and develop his talent rather than pursue a law practice or work for the government.

"My father decorated his office with my paintings," Purvis says. "He always told me I had a gift that he didn't possess."

Purvis is currently working in watercolor. His subjects include portraits, landscapes, and "whatever it is I want to do," he says.

In the past he has done several one-man exhibitions of photography in London, New York, Paris, and Amsterdam. Purvis wrote Dutch Graphic Design 1918-1945, published by Vendler Rhineholt. His engagement with the Dutch aesthetic is evident in his art, teaching, and writing.

After seeing Purvis' work in America, representatives of the Koninklijke Academie Van Beeldende Kunstens-Gravenhage (the Royal Academy for Fine Arts at Gravenhage) invited him to teach there. After a short time he was offered a permanent visiting scholar's postion. Although he no longer teaches for the Academy with the same frequency, he does maintain a connection with it through an exchange student program he has established at BU.

"Text" seems to have a more prominent presence in Purvis' life than in the life of many visual artists. "Collage," he says, "is one of my great loves -- I write like I make collage: take a bunch of stuff and put it together."

Purvis says more specifically that he likes the connection to history he achieves through collage. He collects and makes use of whatever he can find; one collage includes bits of some 18th-century Dutch documents. "I horrify my friends sometimes," he says with a grin. "Once I bought some Siberian stock certificates. We heard after I cut them up that the Russian government was starting to redeem some of them. 'Well then,' I said, 'it will just raise the value of my collage.' "

|

|

|

On Wednesday, September 30, Boston Symphony Orchestra violinist and School for the Arts new faculty member Lucia Lin joins the Muir String Quartet for her first Boston area performance as a member of the ensemble. Lin, along with Muir Quartet violinist Peter Zazofsky (bottom, right), violist Steven Ansell (top, left), and cellist Michael Reynolds, will perform Mozart's Quartet in G, K.387, Ravel's Quartet in F, and Beethoven's Quartet in E minor, Op. 59, No. 2, at 8 p.m. in the Tsai Performance Center. Photo by Susan Wilson |