![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 26 March 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 28 |

Feature

Article

For education reformers, a 10-year milestone

Center's virtuous mission carries on

By Hope Green

Ten years ago, School of Education Professor Kevin Ryan launched BU's Center for the Advancement of Ethics and Character (CAEC), hoping to counter what he saw as a disturbing trend in public school education.

"Teachers were dealing with history and literature in a moral vacuum," he says. "I was appalled by how they were reduced to trying to be entertainers or psychological counselors, rather than an extension of parents who have a responsibility to teach proper behavior. As a result, students started to engage in a lot of disorderly conduct, bad language, and disrespect for each other and their teachers."

Educators feared that imposing values on children smacked of religious proselytizing and would invite parental lawsuits. Yet surveys showed that most parents wanted an ethical context for their children's instruction. "As a former student and having been a high school teacher myself, it became clear that teachers are more than information jockeys," Ryan says. "They have a responsibility to help kids learn virtues like self-control, an understanding of justice, and an ability to persist at hard tasks."

|

|

|

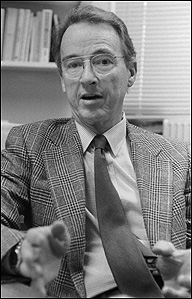

SED Professor Kevin Ryan is founding director of the Center for the Advancement of Ethics and Character. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky |

The center's mission, Ryan says, is to influence both the training of teachers and the national dialogue on character education. Research is a major part of that quest. In a recent national study of 650 teacher-training programs, the CAEC found that 90 percent of their deans and directors think character education is important, but few provide aspiring teachers with a framework to pass along ideas about morality to youngsters. Ryan was not surprised by the results.

"What we're trying to do is call attention to the problem and influence state agencies that regulate teacher education," he explains. He is scheduled to report the findings at an April press conference in Washington.

Another large-scale CAEC research project, funded by the Templeton Foundation, identifies 10 schools annually from across the United States with exemplary programs in ethics for their pupils. The schools are intended to serve as national models. Last year, the first 10 Schools of Character were named in collaboration with a Business Week institutional awards program.

Professional education is one of CAEC's most important activities. During the past nine years, more than 600 elementary and secondary school educators have attended its summer Teacher Academies, intellectual retreats where participants reflect on moral lessons drawn from an array of humanities texts ranging from ancient philosophical works to the poetry of Langston Hughes. Teachers respond to the retreats enthusiastically and bring what they have learned back to their classrooms, according to Ryan and his colleagues.

So far, sites for the summer institutes have included Boston and parts of New Hampshire and Georgia, but eventually the center hopes to establish a federation of academies nationwide.

Over the years, the CAEC has advised educators around the world, often with on-site workshops. It has worked most intensively with the Benjamin Franklin Classical Charter School in Franklin, Mass., where temperance, prudence, fortitude, and justice are regular topics of classroom discourse. During a unit on World War II, for instance, Deborah Farmer (CAS'98, SED'98) asked her seventh graders to ponder the differences between bravery and its impostor, recklessness. In response to a recent outbreak of lunchtime gossip, she coached the class in drafting a recess behavior policy.

Rather than stir resentment, Farmer says, the focus on old-fashioned character issues "is a great relief to the students, because they feel cared for and taken seriously by their teachers."

Not only does the CAEC aim to make character education more of a priority, says Ryan, it also wants to guide the way it is taught, as spelled out in the center's Character Education Manifesto in 1996. The seven-point document was endorsed by eight state governors and such luminaries as former U.S. Education Secretary William Bennett.

Ryan, who coauthored his latest book, Building Character in the Schools (1999), with Bohlin, criticizes schools that have responded to political pressure for moral education with window dressing or attempts at a quick fix. Many of them, he says, simply put a new spin on such methods of the 1970s as values clarification, a model in which teachers facilitated classroom discussion of moral dilemmas but avoided imposing their own views. By contrast, he says, the CAEC believes schools should openly promote virtues such as self-discipline and concern for the poor.

"The mission of a teacher to engage in these core concepts," Ryan says, "is the social glue of society."