![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 26 March 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 28 |

Feature Article

|

|

|

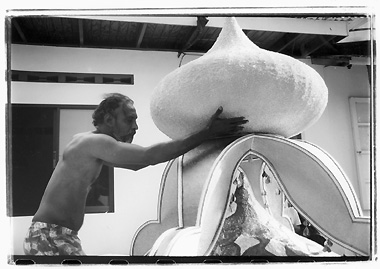

Master builder Noble Bisnath of St. James, Trinidad, crowns his tadjah, or model tomb, during a Shiite Muslim festival that is the focus of an award-winning film by Frank Korom, CAS assistant professor of religion and anthropology. Photo courtesy of Guha Shankar |

Festival in Trinidad

BU prof wins mini-Oscar for film of ethnic rituals

By Hope Green

Every year during Muharram, the first month of the Islamic lunar calendar, Shiite Muslims in Trinidad follow 10 days of prayer and fasting with 3 nights of festivity. To a steady pulse from hundreds of sheepskin drums, a multiethnic crowd parades through St. James -- a district outside the capital city, Port of Spain -- carrying colorful flags, pole-mounted shields symbolizing the moon, and ornate, mosque-shaped model tombs called tadjahs. At the end of the observance, celebrants toss the beautiful and painstakingly crafted tadjahs into the sea to symbolize the ancient sacrifice of their martyr, Imam Husayn.

Frank Korom, a CAS assistant professor of religion and anthropology, captured the Shiite rituals in his 1998 documentary film Hosay Trinidad, and earlier this month the film won a prize at UCLA's Vitas Ethnographic Film Festival -- an honor that Korom describes as "a mini-Oscar for ethnographers."

"I was surprised and also very pleased," says Korom. "My coproducer and I put six years into the editing process, and it took a lot of thought and energy."

Korom, who began teaching at BU in September, specializes in South Asian culture. In the 1980s, his research on the Indian diaspora took him to Trinidad -- the larger of two Caribbean islands composing the British dominion of Trinidad and Tobago. Muslims have inhabited northern India since the Middle Ages, and thousands of them, along with multitudes of Hindus, migrated to Trinidad between 1845 and 1917 to become contract laborers. Shiites make up only a small percentage of the island's Muslim population, but members of many ethnic groups join in their religious festival.

|

|

The observance of Muharram, named for the month in which it occurs, is a period of ritual mourning for Imam Husayn, a seventh-century martyred grandson of the prophet Muhammad. Its rituals vary in different regions of the world. In Iran, the street parade is a somber passion play of the events leading up to his death, in which participants draw their own blood from surface wounds to symbolize Husayn's suffering on their behalf. But in Trinidad, where the holiday period is also referred to as Hosay, the martyrdom is reenacted in a lively ceremony. Such merriment, complete with drinking and dancing in the streets, has been a point of contention for local Sunni Muslim religious leaders, who have argued for years that the Hosay festival should be banned.

So ardent were their protests that Korom found himself caught up in the controversy. "It put me in a funny moral and ethical position," he admits. "On the one hand, as an anthropologist and scholar of religion, you want to go in there and attempt some neutrality. But the more you get involved in the people you study, the more engaged you become. So you're always trying to negotiate these two roles in the field, as both the neutral observer and the person who empathizes with the people being studied."

|

|

|

The tadjah procession on Big Hosay Night. Photo by Peter Chelkowski, Jr. |

But the project's real challenge was the editing phase, which meant distilling a coherent 45-minute documentary film from 40 hours of raw footage. Between 1992 and 1998, while juggling his job as a curator at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, N.M., he made frequent trips to Los Angeles to edit the film with coproducer John Bishop. Although Korom is a prolific writer in his field, he was motivated to film the Trinidadian rituals so that he might reach an audience beyond academia. "I am completing a book on the topic," he says, "but it cannot possibly capture all the dimensions and beauty of it the way film can. Words just fall short. And this project also allowed me to bring out my creative side." The documentary is not Korom's first; he also produced Dorjee Gyaltsen: A Tibetan Painter in Exile as part of an installation at the folk art museum.

Born in Yugoslavia, Korom hopes to screen Hosay Trinidad during an annual Sarajevo film festival in the fall. At the Vitas event, he says, a Bosnian member of the audience told him she was moved to tears by the cross-cultural harmony depicted in his documentary.

Korom has been showing Hosay to his students at BU, where he says he likes to enliven his classroom lectures with "visual vitamins."

"The film is an attempt to convey some meaning without imposing too much interpretation, which is why it has so little narrative," he says. "We wanted the images to speak for themselves."