![]()

Departments

![]()

|

16 July 1999 |

Vol. III, No. 2 |

Feature

Article

Einstein's brain power not just in its contours, profs say

By David J. Craig

Anyone skimming the front page of a newspaper June 18 might have been left with the impression that scientists have discovered what made the mind of one of this century's greatest thinkers tick.

A study on the relatively large size of one section of Albert Einstein's brain, published the next day in the British medical journal Lancet, inspired reports in almost every major U.S. daily. Many of those articles suggested that the physicist's intelligence could be attributed to the size of the parietal lobes in the front of his brain.

But several BU professors think that the study proves nothing. They insist that to understand Einstein's accomplishments one should look at his upbringing and the independent spirit he exhibited. They add that the spotlight the media turn on this kind of biological research is unwarranted, leading casual readers to believe that the findings are of great consequence.

"The idea that we're anywhere near the point when we can pinpoint what it is that characterizes creativity or genius in terms of the gross anatomy of the brain is preposterous," says CAS Professor Emeritus John Stachel, who directs the BU Center for Einstein Studies. "I have no doubt that there are physiological correlates to brain function, but to jump from the anatomy of Einstein's brain to his creativity is to neglect the whole social milieu in which he grew up.

"Einstein would have been horrified," Stachel continues. "He never considered himself a genius. He thought he was just persistent. And he made it clear he wanted to avoid any fetishism of his body. He was cremated and his ashes spread in an unknown place."

|

|

|

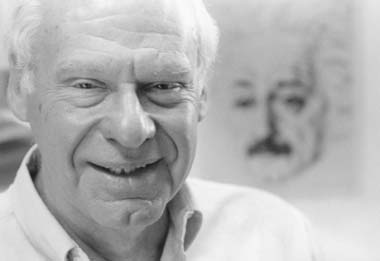

CAS Professor Emeritus John Stachel ponders the work of fellow physicist Albert Einstein at the BU Center for Einstein Studies. Photo by Fred Sway |

The researchers concluded that the parietal lobes in Einstein's brain -- which was removed and preserved after his death in 1955 at the age of 76 by a doctor who reportedly did not have permission to do so -- are 15 percent larger, on average, than those of a cohort of 35 living humans with ordinary intelligence.

The study also found that the two sections of Einstein's parietal lobes are not separated by a recess as in most humans brains, leading Witelson to speculate that the large number of connections between the cells in Einstein's brain may have contributed to his intelligence.

News reports in the June 18 editions of the New York Times and the Boston Globe touted the study as a breakthrough in solving the mystery of how human intelligence works.

That didn't thrill Stachel, who travels the world conducting conferences that promote Einstein's scientific, political, and ethical thought.

He says that to understand Einstein's accomplishments, one should look first to his personal experiences -- growing up a Jew in predominantly Catholic Munich, Germany, being alienated from classmates and teachers because of his intellectual strong-headedness, and being isolated from his religion after studying popular scientific thought.

"Einstein came to his intellectual independence through his life experiences," says Stachel. "He had an ability to focus on a problem endlessly, but there are a lot of kids who are persistent. However, Einstein's skepticism toward authority, for example, came from thinking independently and not losing sight of his goals."

Stachel also thinks that Witelson's study is part of a trend in scientific thought that underestimates the effect of social and cultural factors on shaping human personality and behavior.

"In recent years there has been a resurgence of biological reductionism that tries to find simple biological explanations for very complex aspects of human behavior," he says. "To try to do this with something as complex as creativity seems particularly impossible. And I find it dangerous that this kind of things feeds into biological reductionism and contributes to racism and sexism.

"I think the media report such studies often," Stachel continues, "because it's easy and you can sum it up in a headline."

CAS Biology Professor James Traniello says that while biology has made credible causal links between anatomy and animal behavior by comparing different species, the usefulness of studies such as the one on Einstein's brain is less evident.

"Scientists have always been trying to discover an organic basis for human traits, and the whole area is fraught with poor science and pseudoscience done by people with political agendas," explains Traniello, who admits he has not read Witelson's study. "And there's an enormous amount of reductionism out there. We're always reading about how scientists have discovered a gay gene or a fat gene. It makes you think there's a very straightforward relationship between genes and behavior, and that's not true."

Which leads to the question, what does Witelson's study tell us? Witelson writes in her conclusion that the results "predict that anatomical features or parietal cortex may be related to visuospatial intelligence."

Chantal Stern, a CAS assistant psychology professor who studies brain function, thinks that no clear conclusions can be drawn from Witelson's study.

"Because Einstein used that part of his brain from an early age, it probably helped the parietal lobes develop in that way," Stern says. "There have been a lot of recent studies showing that children trained in music have better math ability."

One conclusion that can be drawn from an inspection of Einstein's life, argues Stachel, is that when an independent spirit is focused, good things happen. He points to the courage it took for Einstein to think outside the concept of ether -- a word early 20th-century physicists used to refer to the static matter they believed existed in all space and in relation to which any object's motion could be measured -- when developing the special theory of relativity.

"The reason Einstein succeeded is because everybody else was working on the complex of problems that led to the special theory of relativity on one line -- to develop the ether theory further," says Stachel. "Einstein completely dropped the ether theory. It took him more than 10 years to solve the problem. All that time he was alone, going over the same ground over and over again until he came up with his miraculous theory."