|

|

||

|

|||

Wingéd

chorale

In birdsong, CAS biologist hears more than male voices

By Tim Stoddard

|

|

|

|

AMouth agape, this young cardinal knows how to say, “Feed me.” But it will take several months for it to learn how to sing like an adult. In her lab, Ayako Yamaguchi has found that female cardinals learn to sing about three times faster than males, but that males ultimately acquire a wider repertoire of songs. Photo by Ayako Yamaguchi |

|

Boston’s flowerbeds are still days away from a burst of daffodils,

but the feathered harbingers of spring arrived on campus weeks ago, belting

out their melodies from tree branches and powerlines. Songbirds like

the Northern cardinal have been adding their voices to BU’s urban

symphony, and for Ayako Yamaguchi, a cardinal’s song is more than

a pleasant assurance of spring: it’s a biological puzzle that may

shed light on how birds and whales and humans learn to vocalize.

Yamaguchi,

who recently joined the CAS biology department as an assistant professor,

has been listening closely to young cardinals, and she’s

found that the drab brown females learn to sing three times faster than

the flashy red males. It’s the most dramatic example of learning

disparities between male and female animals found to date, she says,

and it’s leading to new insights into the sexual differences in

singing.

“

People have studied birdsong for about 50 years now,” Yamaguchi

says, “and so we know a lot about how and when birds learn to sing,

and how accurately they can imitate songs. But we don’t know anything

about how females learn songs because all the research is done on males.”

Male

birds have taken center stage, she says, because in temperate zones,

there are only a few species in which both sexes sing. And since the

majority of biologists live and work in temperate zones, it’s natural

that the literature has focused on male singers. But that leaves a significant

hole in the literature concerning female songbirds, which is especially

acute in the tropics, where singing is common in both males and females.

As a graduate student, Yamaguchi decided to blaze a new trail in birdsong

research by comparing male and female vocal learning in the Northern

cardinal, one of the few temperate species in which both males and females

sing. She collected chicks in the Arizona desert and carried them in

a cotton-ball-padded yogurt container back to her laboratory at the University

of California, Davis, where she began the laborious process of raising

the little birds. “You have to feed them every half hour from six

in the morning to eight at night for the first two weeks of their lives,” she

says. “It’s a pretty intensive effort.”

The chicks

grew up in special sound chambers with microphones and speakers that

play back the songs of adult cardinals. It takes about a year for

a cardinal to learn to sing properly, Yamaguchi says, and like human

infants acquiring speech, young songbirds learn to sing by imitating

adults. The early months are part of the so-called sensitive phase, when

the chicks don’t say anything, but listen attentively to singing

adults to memorize their songs. Then the practicing begins. “Their

initial attempts are pretty miserable,” she says, “but they

practice and practice until it matches the memory that was formed earlier

during the sensitive phase.”

Yamaguchi found that male and female

cardinals actually have sexually distinctive voices, like sopranos and

baritones. Even an avid birdwatcher

would be strapped to pick out a male cardinal’s song from a female’s,

however, but in 1998 Yamaguchi analyzed the songs of juvenile birds and

found that the females sing with more overtones, creating a slightly

nasal sound. Young males also go through a nasal, warbly phase as their

testosterone kicks in, she says, but it’s as though the females

continue to sing with an adolescent male’s voice.

More important,

Yamaguchi discovered that female cardinals memorize adult songs three

times faster than males. While both sexes ultimately learned

the same number of song types, the females’ sensitive phase was

only a third as long as the males’. The different learning rates

may reflect an evolutionary adaptation. Like other songbirds, juvenile

cardinals disperse from their parents’ territory about 45 days

after hatching to establish their own turf before their first breeding

season. Away from their natal nest, the young cardinals are suddenly

immersed in the new song dialects of other adult cardinals. It appears

that females lose the ability to learn new dialects when they disperse,

while males are able to learn them and “fit in” with their

new neighbors.

“

It might be that males retain the ability to learn songs longer than

females so that they can have a better chance of establishing territory

in a new area,” Yamaguchi says. “For males, song-matching

and fitting into the crowd in a new place are really important, while

they’re not for females.” It’s not clear why female

cardinals have a shorter window of vocal learning, she says, but then

again, “we don’t really know why females sing at all, or

how they use their songs.” One hypothesis, she says, is that females

sing as a species identification tool, a greeting card to male cardinals

that says, “I’m an eligible mate; come court me.” Other

researchers have proposed that female cardinals sing to shoo away brightly

colored mates from the nest when a predator is nearby, warning the males

not to attract attention to the vulnerable chicks. “I know that

female cardinals also use songs in aggressive behavior,” Yamaguchi

says. “I’ve seen females battling each other in the field,

and they’re singing the whole time as they bang into each other.”

Pavarotti of the pond

|

|

|

|

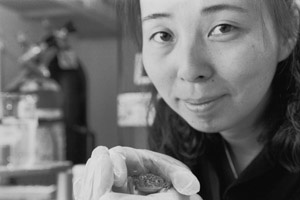

A frog in the hand: In Ayako Yamaguchi’s lab, croaking African clawed frogs are shedding light on the complex crooning of songbirds like the Northern cardinal. Next spring she will raise cardinal chicks in her lab to investigate the different ways males and females learn to sing. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky |

|

Yamaguchi is still feathering

her lab at BU, but already she’s

found a home for the African clawed frogs that she has recently begun

studying along with songbirds. She wants to better understand the neurological

changes in male and female cardinals as they acquire song, but it’s

difficult to track changes in a bird’s brain through time. Instead,

she has turned to a simpler singer, the African clawed frog. Both male

and female frogs vocalize underwater with a single pair of muscles in

the larynx. Male frogs purr like a revving engine, while females pipe

out a slower-paced “crick . . . crick . . . crick.” In her

postdoctoral work at Columbia University, Yamaguchi discovered that both

male and female frogs were sending the same neural signals from their

brains to their voice boxes to make the sounds. But the male frog brains

somehow send the “crick” message faster and more accurately,

so that their laryngeal muscles contract at a faster rate than those

of females.

“

That finding was quite new, and it was quite a tour de force to demonstrate

it so clearly in frogs,” says Peter Marler, a songbird expert at

U.C. Davis and Yamaguchi’s Ph.D. advisor. “Ayako’s

great achievement was to show that it’s not sufficient simply to

look at the vocal apparatus to explain the difference between male and

female calling. You have to look back up into the brain for a full understanding.”

At

the larger scale, Yamaguchi’s work may someday have applications

for other species that learn to vocalize, such as Homo sapiens. Human

infants learn to speak the same way that cardinal chicks do, and the

cardinal results also parallel the subtle but consistent gender differences

in human speech acquisition. “Ultimately, the question is, how

do male and female brains work differently?” she says.

It’s

a fitting question, considering that Yamaguchi became interested in language

acquisition as she herself was learning to speak English

at the age of 15. Born and raised in Tokyo, she spent a year of high

school on an exchange program in southern Utah. “At the beginning,

I couldn’t understand a word they were saying,” she says

without a trace of accent. “Then slowly I began to understand and

imitate the vocalizations that people were making, and I thought it was

such a fascinating process, converting auditory information into motor

output.”

Returning to Tokyo, Yamaguchi enrolled in the prestigious

Japan Women’s

University, where studying biology was something of a challenge. “The

university prides itself on producing good wives and wise mothers,” she

says with an ironic grin. “Eighty percent of the prime ministers’ wives

are from our college.” A skilled experimentalist, Yamaguchi admits

that cooking and cleaning are not her forte.

Yamaguchi’s lab is

unusually quiet these days, but she expects that to change next spring

when she resumes her cardinal work. The new

cardinals will learn to sing in a sound isolation room in the basement

of the biological sciences building, hopefully out of earshot of faculty

and students upstairs. “When they start singing, the sound pressure

is about 90 decibels at one meter away,” she says, “which

is like standing on a subway platform and having a train pass by.”

![]()

4

April 2003

Boston University

Office of University Relations