Envisioning Our Future: Boston University in 2030

April 25, 2018

Dear Colleagues,

The semester is headed into the homestretch as I write my spring letter. This year I want to use it to catalyze discussions that we are initiating to renew our Strategic Plan and to create a vision for Boston University in 2030. This letter is addressed specifically to our faculty; however, it may be of interest to all members of the University community.

I have asked Jean Morrison, University Provost and Chief Academic Officer, to develop the Plan in three steps. The first step, already underway, is an assessment of our strengths and weaknesses, measured by:

- the quality and impact of our academic programs, informed by the results of Academic Program Reviews; data about student outcomes; and data gathered about how our graduates fare in making the leap to work and career,

- the state of our residential campus community,

- the condition of our current facilities, and

- the financial strength of the University.

This assessment should be complete by the end of this spring.

The second phase is the formation of a committee of faculty and staff charged to produce a report for all of us to consider and which will be the basis for the next Strategic Plan. The last stage involves finalizing the Plan and an aligned financial strategy. This will be done in consultation with the faculty, University leadership, and the Board of Trustees.

Developing our Strategic Plan for the next decade is critically important, and I hope the effort will stimulate many conversations across the University. As we begin, I would like to share with you some reflections on the University today, the world around us, and a possible theme.

First, why is planning so important to Boston University? I know that there is a healthy skepticism about planning in a university, particularly when the adjective “strategic” is applied. Louis Menand said, “Being an academic professional means—often, although by no means always—maintaining a skeptical, sometimes antagonistic relation to the institutional and organizational apparat that credentializes and supports you.”1 In response to such skepticism, I would offer the observation that, as a private university with a relatively small endowment,2 we do not have the luxury to be unfocused or attempt to do everything. In the last decade, we have proved that we can be very successful when guided by a purposeful plan that defines priorities, informs resource allocation, and elicits philanthropic support.

Our first Plan, Choosing to be Great, adopted in 2007 and revised in 2014, described the institution we aspired to be, focusing on the internal commitments and actions needed to reach this goal; these are listed in the Appendix. I believe these commitments have served us well and should endure.

Absent from the 2007 Plan was speculation about or description of what our leadership role in the higher education community might be. I believe it is time to broaden our ambitions and think much more about our capacities as a large (and increasingly recognized) research university with breadth and depth and the distinctive ways in which we can bring those capacities to bear in educating future generations and fulfilling our obligations to serve society.

I believe we are at an inflection point where the societal roles of universities are being redefined. Developing our vision for the University in 2030 gives us the opportunity to lead in a rapidly changing environment.

What We Have Accomplished and How

The case for launching a new planning exercise is best made by reviewing what we have accomplished in the last decade.

First, we have realized much of what was envisioned in the 2007/2014 Plan. We have created a vibrant, forward-looking university that has taken its place as one of the highest quality, large, private research universities in America. Of our many accomplishments, several stand out:

- For the fall 2018 freshman class, we received 65,400 applications for the 3,300 positions in the class and expect our acceptance rate to be below 22%. The students we enroll are increasingly diverse, academically accomplished, and ambitious.

- Last year, our undergraduate six-year graduation rate approached 87%, the highest in our history.

- In 2012, Boston University joined the Association of American Universities (AAU), putting us among the best public and private research universities in North America. This year we will direct over $400 million in externally sponsored research.

- In fall 2019, we will conclude our first-ever comprehensive capital campaign. We met our original goal of $1 billion well ahead of schedule. The Board of Trustees raised the goal to $1.5 billion and extended the campaign. Our fundraising total stands at almost $1.4 billion with 18 months to go. Over 140,000 alumni and friends have supported the University in this first campaign.

- Our endowment has reached the $2 billion milestone, and our Moody’s bond rating has climbed to Aa3 stable from A3 negative in 2005. Both are indicators of the increasingly robust financial condition of the University.

The core ingredients of our success have been simple. We have worked to hire the very best faculty members possible (over 52% of our professors have joined the University since 2005) and to create the environment where they can succeed at research and teaching. Most of you know, I believe, about the new programs initiated, facilities built or renovated, and enhanced supports provided because of our sound operating model and alignment with the priorities of our Plan.

Most importantly, in a mutually reinforcing dynamic, educational and research programs led by our faculty are attracting some of the world’s most ambitious, creative, and academically talented students to the University. The demand for places in our undergraduate class is reflected in the consistently increasing number of applications and the academic accomplishments of admitted and enrolling students. The stature of our professional programs is evident from rankings and competition for admission. Because of our increased commitment to doctoral student funding, we are also raising the quality of doctoral programs and recruiting ever-better graduate students.

We are a significantly different institution from the one we were in 2005. We should envision what lies ahead and develop plans based on where we are today. And we must take into account societal and economic changes that we could see glimmers of in 2005 but which are now new realities.

I will describe these shifts below. But first, I want to state the thesis that I will return to at the end of the letter. Great research universities have two essential attributes: demand for excellence in all facets of their education and research programs, and a striving for relevance in the world through research, education, and service. I believe we have a strategic opportunity to make it a core principle of the University that we be an institution where faculty and students from across all our schools and colleges interact and collaborate in their academic programs and research, while always striving for excellence. If we focus on the possibilities from interactions across traditional academic boundaries, we can create unlimited possibilities for our students and faculty, and in so doing create a brilliantly distinctive future for the University.

I elaborate on this organizing principle below and explain how, in my view, such a principle would influence the evolution of the University and the development of our Strategic Plan.

First, I begin with some background about Boston University and the world today.

Boston University Past and Present

Boston University has never been insular. Our abolitionist founders defined values that were tested and tempered in the strife of our Civil War and which have stood the test of time, even as we have grown and changed, adapting to meet new needs but ever committed to service and inclusivity. Boston University’s story is different from the story of many of our peers. We emerged from World War II as a regional, commuter university focused on undergraduate and graduate professional programs and with pockets of excellence in research and scholarship.

From this urban and regional base, Boston University has evolved into an internationally prominent, uniquely urban yet residential, private research university. Today we attract diverse, academically accomplished, and ambitious students from around the world, who come to study with an exceptional faculty composed of wonderful teachers and renowned researchers and scholars. We offer prospective undergraduate students a palette of programs in our professional schools and the sound foundation of a quality education in the liberal arts and sciences. Our new general education program—the Hub—forms our first common educational core for all our undergraduate students and is designed to impart the fundamental knowledge and contemporary skills our students need to lead productive and meaningful lives. It will, I believe, become the common, binding thread in the educational experience of every BU undergraduate.

Our educational programs are not the only draw for our students. Our location and our residential environment also are appealing. Students join our residential community, in the heart of Boston, which is a vibrant college town but also a recognized international leader in the urban transformation to a 21st-century economy. It is a model for the environment in which the majority of our graduates will work and live. Boston University embraces Boston. We long ago realized that when the City prospers, we attract the very best faculty and students. We have consistently led all local universities in programmatic and financial support of Boston.

However, we no longer focus primarily on our region. Our students and faculty come from all across the United States and around the world. The University embraced academic globalism early by recruiting international students and by developing one of the nation’s largest study-abroad programs, through which we offer students academic opportunities and internships around the world and across the country, while working to ensure these programs and internships align with our requirements and standards. The global reputation of Boston University is outsized, as measured either by our pool of over 13,000 international applicants for undergraduate admissions or our global rankings. I know of no other major university which enjoys a higher ranking in the USN&WR international scoring than it does in their ranking of only domestic institutions. In 2018, USN&WR ranked BU 39th among all the universities in the world or 28th among American institutions, while listing us as 37th in their national rankings.

As I suggested earlier, BU has emerged as a major research university. The concept of an American research university is not old; its roots are in the landmark report, Science, the Endless Frontier, commissioned by President Roosevelt and submitted to President Truman in July 1945.3 The report’s authors argued that:

The Government should accept new responsibilities for promoting the flow of new scientific knowledge and the development of scientific talent in our youth. These responsibilities are the proper concern of the Government, for they vitally affect our health, our jobs, and our national security. It is in keeping also with basic United States policy that the Government should foster the opening of new frontiers and this is the modern way to do it. For many years the Government has wisely supported research in the agricultural colleges and the benefits have been great. The time has come when such support should be extended to other fields.

As a result, the National Science Foundation was established by Congress in 1950 and with it the system of peer-reviewed, federal research support, first for the physical sciences and engineering, and later for life and health sciences through the expansion of the National Institutes of Health. Research universities have enjoyed this support for over half a century, a period in which their quality and impact has become admired and emulated worldwide.

Whether by choice or circumstance, Boston University did not develop early in its history as a major American research university: in FY1971 our externally funded research amounted to only $13.5 million. We made the transition later, starting in the 1980s with significant growth in the life and physical sciences, and have accelerated in the last two decades.

The result has been remarkable. Today our faculty is composed of renowned researchers and scholars. We compete with the very best private and public universities to recruit and retain the people—faculty, doctoral students, and postdoctoral researchers—who lead our research enterprise. The competition is intense. We have invested heavily in the physical and administrative infrastructure required to win, but more will be needed as we continue to increase the number of research-active faculty members on the Charles River Campus. The opening of the Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering on the Charles River Campus and our bringing fully online the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, along with ongoing renovations on both campuses, are part of our efforts to provide the necessary support for advanced research. Later this spring we hope to announce a large investment in facilities for the computational and data sciences to house our expanding commitment to these important areas.

Boston University’s recent progress has been made despite essentially level federal support for research universities (particularly when measured against other rising indices). By most measures, the peak of federal support (inflation adjusted) in American research universities occurred several decades ago, with a levelling off that accompanied the end of the Cold War and growing pressure on the federal budget from entitlements. Waning or flat federal support has led to cost shifting to universities. A greater portion of research costs is now borne by universities, and private foundations have become an important sponsor in some domains. An analysis conducted by the AAU in 2014 showed that 23% of all support for research comes from universities. It is increasingly expensive for universities to be competitive in research. Even though the Omnibus Bill that just passed for fiscal year 2018 gives us a momentary reprieve, the pressures on the federal budget make it unlikely that such increases will become the norm. Competition for external research support will be keen, and winning will require the most creative research ideas, collaborations among top researchers, and significant University support.

The World Around Us

The world around us has changed dramatically in the last decade as some trends that were emergent a decade ago have accelerated. The world today is more global, more urban, more multicultural, and more digital than ever and will be even more so in 2030. Here are some figures that capture the momentum behind these shifts. Today, 54% of the world’s 7.6 billion people live in cities, up from 34% of 3 billion in 1960, and the estimate for 2050 is that 66% of 9.6 billion people will be city dwellers. The global challenge is to develop economies and societies that can sustainably support this urban population with food, water, security, healthcare, and meaningful work. The population pressure on our planet will force us to accelerate our move away from carbon-based energy and to better manage water and land. New sustainable development strategies will lead to denser urban centers. Boston University is in a position to contribute to the solutions of these challenges, and, with our Climate Action Plan as our road map, to be a model for the actions needed by a community.

Two trends in our country are particularly critical—our changing demographics and the ongoing restructuring of our economy.

Diversity

Today, America is more diverse than at any time in our history; according to US Census data the percentage of responders identifying as either African American, Hispanic, or Asian has jumped from 14.2% in 1960 to 33.8% in 2010. This demographic swing will continue with people of these heritages estimated to account for 49.2% of our population by 2040.

This same demographic transformation is reflected in our student body. Last year our undergraduate applicant pool passed a milestone. For the first time, the sum of the United States citizen applicants identifying as being either of African American, Hispanic, Native American, or Asian origin exceeded those identifying as Caucasian. For our fall 2018 freshman class, with 57.3% of our admitted domestic students being of these origins, we are well on our way to being a majority-minority academic community.

Simultaneously, rising economies in different regions of the globe have stimulated the demand for quality higher education and, with it, applications to Boston University: international applications for positions in our undergraduate class stand at over 13,000, a 455% increase since 2005. As long as our country remains a welcoming environment for people from all nations, this number will continue to rise with global economic development.

Overall, we have one of the most diverse student bodies of any private university in America. It is essential that Boston University be a richly diverse and inclusive residential community and that we prepare our graduates to be reflective, informed citizens of this country or another. Continuing to expand the diversity of our faculty will be important to fulfilling this goal.

Offering access to the most academically ambitious students, irrespective of means, is central to our mission and the aim of increasing student diversity. For undergraduates, our expanded financial aid commitment to Pell Grant recipients is a major step toward measurably expanding economic access. This academic year we will provide almost $250 million in undergraduate financial aid—the vast majority need-based—a number we expect to grow by almost 20% over the next three years.

Inescapably, the value of a university education is linked to graduates’ view of its impact on their careers, measured by either financial gain, professional satisfaction, or both. We must give our students an education that translates to employment when they leave Boston University and that is a sound foundation for their lifelong careers. By itself, a college degree has long been the gateway to economic success. Estimates indicate that the average difference in earning potential for a college graduate over a 40-year work life is $650,000 more than for a person with only a high school degree. Even when accounting for the cost of higher education, the net gain of a college degree is substantial over the course of a career, making higher education more important than ever.

But the changing economy and the changing nature of work may create challenges for college graduates. Much has been written about the changing character of the workplace as we move away from our 20th-century manufacturing base. This is not a new trend; the number of manufacturing jobs peaked in 1978 and has been falling since.4 The financial impact for the average American has been stark; for the last two decades, our economy has produced little wage growth for the middle class, a phenomenon that has made college less affordable for many, significantly impacting access to higher education.

Preparing students for a lifelong successful career is perhaps our biggest challenge, because of the speed of the transformation and the uncertainties ahead. Think about the economic transformation that is accelerating as high-speed communications, machine learning, and robots displace jobs and disrupt others. We can’t dismiss these emerging technologies as affecting only manual and transactional jobs. Machine-based intelligence will affect all of us, even those in the most highly educated professions. For example, in legal services, machine learning is now used to “characterize” digitized evidentiary documents, a task formerly performed by professionals. What will be the impact of such technologies on the demand for legal education? The number of LSAT test takers has dropped almost 30% in the last decade as jobs went offshore. Now they will be digitized. What will be the upstream impact on liberal arts degrees that feed the law school pipeline?

To be successful all our graduates will have to continually adapt to changes in the nature of their work. In this dynamic world, they will need to know how to apply what they learn and know how to learn by themselves. And, we hope, they will lead others. Some of their time at Boston University, either on campus or during an internship, must help them hone these skills.

Closer to home for each of us, what will be the role of digital learning in higher education, for undergraduate and core professional residential programs but also for the continuing evolution of the delivery model? We will need to change our use of classroom time as the expert systems underlying digital learning become more powerful. On campus, new approaches to using classroom time, such as “flipped” classrooms and studio learning environments, are springing up all over campus as we experiment with ways to improve student learning and develop the skills of self-learning and collaboration through context-based instruction. Our design and use of space must match these new needs.

Within Boston University, our Digital Learning & Innovation initiative and Metropolitan College are pioneering online delivery for both residential and online students. With digital delivery, the traditional constraints on quality of education, such as student-to-faculty ratio and class size, aren’t relevant; program quality is measured only by learning outcomes. Most likely, this will become the standard to which all of higher education is held.

Finally, when thinking about the external influences on higher education, there is a growing political voice to consider. In a world in cultural and economic flux, it would seem self-evident that the value of higher education institutions would be increasingly recognized, as graduates with advanced skills and the ability to deal with complexity and ambiguity are going to be in demand. But this is not how our country views us today. At a time when more high school graduates are attending college than ever, public opinion about higher education is at a low point. A recent poll by Pew Research Center found voters divided along partisan lines about the value of higher education. Of Republican or Republican-leaning voters, only 36% thought that colleges and universities have a positive impact on the way things are going in the country, compared to 72% of Democratic or Democratic-leaning voters. However, when only graduates of four-year institutions are polled, over 85% believe their college education benefited their careers and personal development.

The issues at the heart of this divide are as complicated as the political dynamics at the center of shifts in our demographics, culture, and economy. As a high-quality private university with high tuition, Boston University is not insulated from criticism. We are in the crosshairs of the debate—just consider which institutions are targeted by the new, ill-considered federal tax on private university endowments.

We need to make the case for our relevance to society. We need to continually tell the story of the success of our students and the positive impact of our research on society. These stories must be meaningful and are best told by neutral brokers, not us. There is an important society-wide narrative about the value of universities because of our research, scholarship, and public engagement. The positive narrative is too often limited to our contributions in science, engineering, and medicine. This impact is obvious, essential to the modern world, and is more easily quantified. Boston University plays an important role in the innovation ecosystem, where inventions and cures, patents, successful start-ups, and job creation are the coin of the realm. Innovate@BU is our investment to help more of our students acquire skills to be innovators and entrepreneurs.

Universities, however, are also essential as the historians and interpreters of our culture and society, functions that are becoming lost in the national narrative. Public debate is fraught and, I would argue, oversimplified, tending to break along ideological fault lines. Critics emphasize the extreme while we in higher education do not always persuasively make the case for the value of our scholarship to the understanding of complex contemporary issues. Challenges such as ending conflict, eradicating poverty, creating inclusive communities, and designing societies that function for all citizens are far more complex than can be addressed by technologists, economists, and business leaders. Humanists, social scientists, artists, and the professions must work together if we are to make progress. This need for collaboration is an opportunity for Boston University.

There is new energy in such collaboration and outreach through the Center for the Humanities in the College of Arts & Sciences and CitySpace at WBUR.

Public trust in higher education is critical to the country and to our future and must be built on the twin pillars of the value of higher education to our students and the technological and cultural importance of universities to society. Boston University’s impact in the world and its reputation as a major private research university will hinge on both, as measured by our many constituencies—our students and their parents, alumni, the leaders who employ our graduates around the world, thought and political leaders in our nation, our neighbors in Boston (and Brookline), and people around the world. Each constituency views us through a different lens, but their perspectives have resonant intersections that may be themes for the University’s Plan.

For almost all of these constituencies, a very important element of their view of us hinges on the answer to the value proposition: is a Boston University education—undergraduate or graduate—worth the cost? Our plan must give us an answer that works on graduation day and for the rest of a graduate’s life.

Three Questions for the Plan

This leads to the three critical questions that should, I believe, be answered as we develop a new plan for the University:

- How do we educate Boston University students to live, succeed, and lead in this changing world? We must continue to shape the classroom and cocurricular experiences of all our students to give them the knowledge and skills to succeed. Today, our students are shaping their educations in unique ways, increasingly taking advantage of the scope and quality of BU. Do we need to do more to formalize and better facilitate these opportunities?

- What will Boston University’s role be—through our research, scholarship, and service—in shaping our society as demographic and technological changes occur? Individual faculty research and scholarship will always be self-motivated and self-directed, but are there ways the University can help energize collaborations that address the larger challenges?

- How do we best organize the University to execute on the commitments that come from our answers to the first two questions and thereby optimize our value to our students and society?

If the Plan offers answers to these questions in the context of the world around us, then we will be well positioned as a large private research university.

A More Integrated Research University

I want to leave you with some thoughts around the third question. Framed differently:

Do we address the challenges and opportunities independently or together?

Today, Boston University is a very highly integrated private research university with faculty and administration who think purposefully and collaboratively about our organization and the allocation of resources. For the most part, we act as one University, working for the betterment of the institution. We try to avoid creating incentives for parochial decisions that are not aligned with the overall mission.

By making the proposal that we become the “most integrated major research university in the country, one that seamlessly connects programs and people across our schools and colleges to create innovative programs and contribute to the solution of the challenges facing society,” I am imagining a university that leverages (ever more effectively) our collective strength to focus on the connections and integration among disciplines.

Boston University is organized like other research universities, using the categories of disciplines, departments, schools, and colleges that first appeared over a hundred years ago and that is common practice in liberal arts and sciences and the professional schools. Departments grant degrees, hire and promote faculty, and are the nodes that connect the elements of the University to the network of similar units in other research universities. This network also constitutes the labor market for doctoral graduates and supports the professional organizations that accompany each discipline. Without discrete disciplines, how would universities execute educational programs or search for new faculty? The established structure of departments and disciplines operationalizes the hiring process and establishes standards and processes for authentication of the quality of programs and people.

For as long as I can remember, the counterpoint to disciplines in universities has been interdisciplinary initiatives that bridge the established disciplines, always with the aim of establishing new research or educational opportunities that live between the disciplines and that would not otherwise exist. Advocates for interdisciplinary reorganization tend to criticize traditional disciplines—sometimes visualized as silos or feudal fortresses—describing them as rigid, territorial, and inwardly focused, thereby limiting possibilities to address important challenges facing the world.

The concept of interdisciplinarity is certainly not new and has been the subject of a great deal of scholarly effort; see, for example, works by Klein5 and Jacobs.6 Organizationally, interdisciplinarity has been an overlay on the traditional departments—interdisciplinary academic programs, research centers and institutes that are often visualized as the rows in a columnar organization of departments, schools, and colleges. How interdisciplinary units report administratively depends on the span of the column, within a school/college to a dean or across schools and colleges to a provost. Klein writes about the hard work of this organization when she says that:

Creating a campus culture that is conducive to interdisciplinary research and education…is a form of boundary work that requires…identifying points of convergence, leveraging existing resources, building capacity and critical mass, platforming and scaffolding the architecture for a networked campus, benchmarking and adapting best practices, creating a resource bank, and institutional deep structuring of a robust portfolio of strategies aimed at programmatic strength and sustainability.7

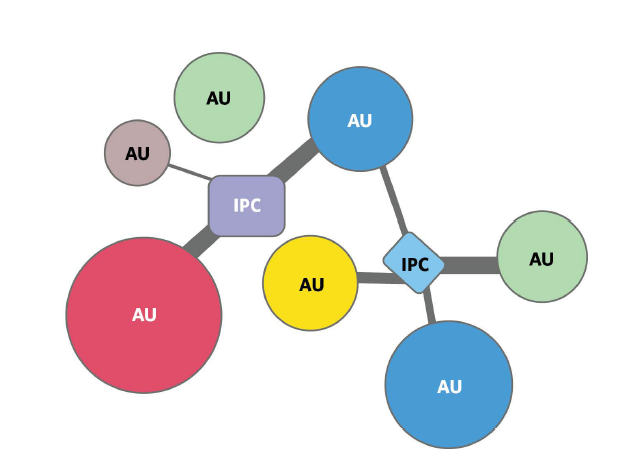

Boston University has been doing this “boundary work” for the last decade, if not before. A simple drawing corresponding to this view is shown below with disciplines, departments, or schools and colleges represented by circles (I will refer to them as disciplinary homes [i.e. academic units]) and the interdisciplinary efforts as connectors between them (I refer to these as interdisciplinary programs or centers [IPCs]). This diagram below (Figure 1) makes clear the challenges of this approach.) First, AUs must be receptive to the collaboration; although each faculty member may collaborate in research more or less across all boundaries (subject to issues of the flow of funds and allocation of time), teaching credit is another matter altogether! This tension can become difficult to navigate, especially for a young faculty member, because it effectively generates dual allegiances to an AU and an IPC, when promotion and tenure are at stake and more influenced by the AUs.

Figure 1. Diagram of traditional academic structure showing academic units (AUs) and Interdisciplinary Programs and Centers (IPCs) as separate, autonomous entities, the connector (solid lines) being faculty, students, and postdoctoral researchers who move between these structures.

An important attribute of Boston University is that we are a comparatively young research university and, as a result, the numbers of research-active faculty, especially in disciplines in high demand, are relatively small. The model described by Klein works best for a very large research university where the established disciplines have larger faculties that can populate interdisciplinary efforts. This is not true at Boston University, especially in the College of Arts & Sciences or in the College of Engineering. Engineering overcomes its having a relatively small faculty size by offering far fewer programs than do other engineering schools. (I have experienced this firsthand as the only chemical engineer in the college.)

Why does department size matter so much? First, it influences the debate about how many faculty members are needed at the core of the discipline and thus the number who are available to populate the boundaries. It also determines (to a significant extent) the degree of tension between the demand for faculty members to teach specific subjects and provide service in a department role versus the demand to recruit faculty who are interested in joining IPCs or interaction and membership in other departments.

Growing our departments is going to be costly and slow. With our almost fixed undergraduate student body size and the pressure to limit tuition increases, faculty growth will hinge on our growing the endowment as another source of faculty salary support. This brings us back to the growing importance of philanthropic support and the 77 professorships created during the campaign.

A different and more radical approach would be to structure the University around topics or challenges of perceived importance. Conceptually, this would translate to hiring faculty directly into our centers and institutes. At least superficially, this approach appears to be more responsive to society and to solve (or at least invert) the problem of the dual allegiance of faculty members. There are, however, significant downsides. First and foremost, it may make secondary the education (teaching) role of faculty within disciplines. Second, the definition of societal needs is transient (albeit over long timeframes), prompting chronic restructuring or trapping a particular institute or initiative in a dated view of the world. Finally, it is important to recognize that creating an interdisciplinary program in global health or environmental sustainability does not necessarily generate solutions to these challenges, so the goal of the radical reorganization may not be achieved.

Where do I stand? I believe disciplines are still essential building blocks of the university, because of their function in the hiring and credentialing of faculty and delivery of instruction, especially in the undergraduate curriculum. But there is no need for disciplines to stand in isolation. The university is stronger, more intellectually vibrant, and more able to adapt to the changing world if disciplines are integrated and interconnected with each other.

By suggesting this, I am thinking about how we can purposefully connect the disciplines and the interdisciplinary programs. How? By moving to faculty hiring processes that are much more collaborative between disciplines and interdisciplinary units that have intellectually similar requirements. As a thought experiment, we could imagine faculty searches for candidates with particular areas of expertise that are of interest to multiple departments and centers.

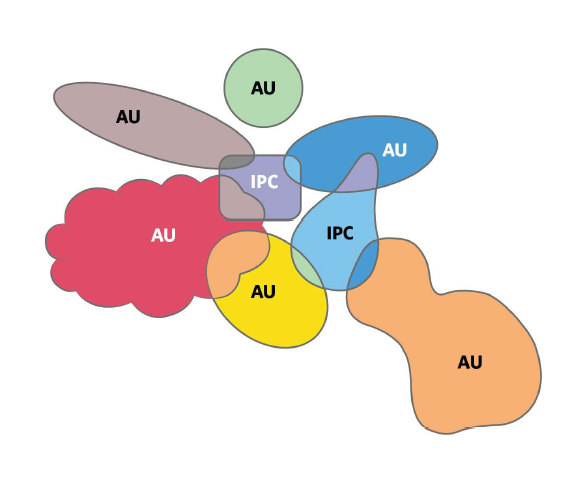

Search committees composed of representatives from multiple centers and departments would review a promising candidate who could, conceivably, have the option of identifying an academic unit where he or she would prefer to be appointed. Teaching assignments could be managed across disciplinary and interdisciplinary boundaries. Figure 2 illustrates this style of organization; note the overlap of AUs.

Figure 2. Diagram of organization with overlap between faculties within traditional departments (AUs).

I have intentionally not drawn the AUs as circular to imply that each one may have a specific strategy about its disciplinary strengths and how they optimally align with other relevant units of the University—all sub-specialities are not equal. Many of our disciplines have such a strategy now, as they do not attempt to be equally strong in every sub-area of the disicipline.

I am not imagining a university composed principally of faculty members with multiple appointments who sit in centers and attend endless faculty committee meetings. How many of these faculty members with dual appointments are needed to enhance the connectivity of our faculty? There are disciplinary and interdisciplinary considerations to the answer. As the recently convened Committee on the Basic Life Sciences at Boston University concluded, there are significant intellectual synergies between the basic life science departments in the School of Medicine and the life sciences in the College of Arts & Sciences that make dual appointments compelling, if we can overcome geographic separation and mediate academic cultural and administrative differences. New dual hiring has begun as a result of the Committee’s work. Here the opportunities exist for a significant number of appointments.

Following this example, I believe there are many opportunities to hire individual faculty members with interests that straddle traditional disciplines and add significant value to the university; in just the last few months I have heard discussions of data scientists interested in K–12 education and anthropologists interested in the origins and impact of epidemics. And there are many truly exceptional young faculty candidates—performing research and scholarship that transcends traditional boundaries—who would be interested in such appointments.

I believe we will be fundamentally transformed when we have a critical mass of faculty with these dual appointments, enough to sustain formal and informal connections between all parts of the University. The new opportunities for our faculty and students would be virtually innumerable. Moreover, we would become a place where faculty whose interests are boundless want to work, and where ambitious and imaginative students want to study. Equally as important, flexible and porous disciplinary boundaries would better enable the University to shape and reshape its future in a changing world.

Developing our Plan, and answering the three framing questions I have posed, is essential for the University to continue its momentum in the coming decade. I hope this short essay is food for thought as we begin the process. We have a wonderful opportunity to expand our role as a major research university. It will be an exciting journey.

Sincerely,

Robert A. Brown

President

_______________________

[1] L. Menand, The Marketplace of Ideas: Reform and Resistance in the American University. W.W. Norton & Co. 2010, p. 107.

[2] Although our endowment has grown to be over $2 billion, income from it accounts for only 4% of our total operating budget, compared to many multiples of this percentage at many of our peers.

[3] This story is well told in D.E. Stokes, Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Brookings Institution Press, 1997.

[4] E. Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

[5] J.T. Klein, Creating Interdisciplinary Campus Cultures. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

[6] J.A. Jacobs, In Defense of Disciplines. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

[7] Klein, page 38.

Appendix

Our 2007 Strategic Plan began with 10 commitments developed by a committee of faculty and staff in a Report called OneBU. The commitments were to:

- Hiring, promoting, and retaining faculty members who are excellent teachers, as well as leaders in research, scholarship, and professional accomplishment.

- Strengthening and enhancing rigorous, well-taught undergraduate education, founded in principles of the liberal arts and professional education.

- Creating unprecedented opportunities for all undergraduates by leveraging the strengths of our schools and colleges.

- Enhancing our professional schools and colleges, building on the pillars of law, medicine, and management.

- Promoting research and scholarship within and across traditional disciplinary boundaries.

- Strengthening and expanding the University’s connection to Boston and the world.

- Expanding and enriching the residential campus and programmatic experiences of our students.

- Aligning our policies, processes, services, operations, and the development of our campus with our values.

- Aligning operating budgets, capital plans, and fundraising with the academic mission and the strategic plan.

- Communicating with and engaging all constituencies of Boston University.

In the 2014 revision of the Plan we included the additional commitments to:

- Enhancing access and student success,

- Increasing the diversity of our students and faculty,

- Innovating in digital learning,

- Working to create a common and compelling vision for undergraduate education,

- Expanding our emphasis on interdisciplinary research and scholarship.