The Paintings on the Doors

How muralist Lena McCarthy transformed a Victorian firehouse

By Marc Chalufour | Photos by Janice Checchio

“Every project is so, so different,” says muralist Lena McCarthy. She has painted murals in Chile, India, and Ireland, as well as the United States. She might paint a 100-foot brick wall one week and multiple sides of a concrete courtyard another. So when she accepted a commission to transform the front of a historic century-old firehouse 30 minutes from her home outside of Boston, McCarthy (’14) wasn’t phased by the challenge.

Jannelle Codianni, director of ātac, the community arts center that has organized exhibits and live performances in the Framingham, Mass., firehouse since 2008, gave McCarthy a lot of freedom with this project—but it was no blank canvas. The mural needed to span three large bay doors. Small window panes would interrupt the design while brick columns topped by iron sconces split it into three panels, creating a giant triptych. McCarthy would be trying to reflect themes of hope, connection, and resilience.

Over four hot days in June, muralist Lena McCarthy (‘14) transformed the front of a historic firehouse in Framingham, Mass., that now houses ātac, a community arts center.

Codianni wanted to hire a local artist and reached out to McCarthy, a past exhibitor at ātac, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We’ve been closed to the public since March and are preparing to start our fall season with virtual performances,” Codianni says. “I’m hoping the mural reminds people we’re still here, even if in a different form for now.”

The two met in April to discuss the project. Then McCarthy got to work.

Finding Her Way to the Wall

McCarthy’s mural career sputtered at first. She founded a mural club at BU, but it was a failure. “We only did one project,” she says, a mural in a Brighton park. The club disbanded after McCarthy graduated.

The fine arts major knew she wanted to paint, but graduated without an immediate career plan. “I was interested in traveling and seeing the world,” she says. She moved to Chile, where she taught English for two years. McCarthy immersed herself in Santiago’s active street art community. “It was a very stimulating environment,” she says. By the time she returned to Boston, she considered murals to be her primary focus.

To work as a muralist, McCarthy says she had to learn “how to be brave and put yourself out in the world and how to make connections with the community you’re painting in.”

McCarthy found that her fine arts training served her well in muralism. But there were still some new skills she had to learn, among them, “How to be brave and put yourself out in the world and how to make connections with the community you’re painting in,” she says. Helping her make that transition has been a series of mentors, including Cambridge, Mass.–based street artist Caleb Neelon, coauthor of The History of American Graffiti.

“There’s a lot of graffiti history intertwined with muralism,” McCarthy says. Part of that influence is the value of visibility—finding spaces that will be seen by the most people. McCarthy estimates she’s completed between 30 and 40 murals, and as she’s established herself, she’s begun considering other factors. “I’ve looked for more projects where the site has meaning, or the site has impact, like neighborhoods that don’t have as much public art.” Sometimes that means a work has an explicit social message: McCarthy collaborated with Neelon on murals in Queens, N.Y., of Gynnya McMillen, a 16-year-old who died in police custody, and Marsha P. Johnson, a gay rights activist who died under suspicious circumstances. McCarthy is planning murals for the playroom and garden at a home for teen moms.

Drawing from Within

Once McCarthy and Codianni had discussed the goals of the firehouse project, she began the same way she starts every project: pencil on paper sketches. “A sensation or a feeling of ‘hope’—that’s an infinite thing,” she says. “I tried to just draw from within myself, what I believe that would look like. It’s my interpretation of the language that they asked me to use.”

McCarthy expects her art to evolve once she begins to paint. “I always have to leave room for it to breathe—I never make things exactly as they look [in the sketch],” she says.

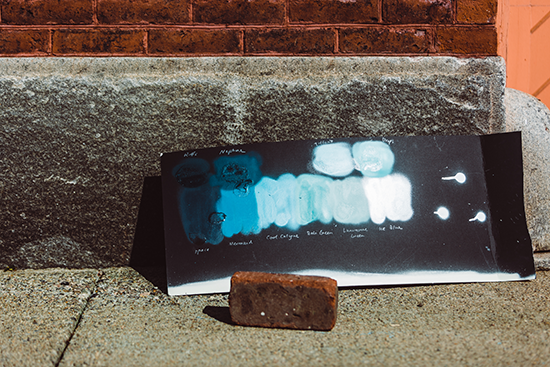

Accepting a commission means agreeing to some limitations. In this case, that meant sticking with ātac’s color palette. Fortunately, the teals and blues contrasted nicely with the building’s red brick. Some commissions involve several rounds of revision, but there was no micromanaging of this project. McCarthy presented four sketches to Codianni and the ātac board. Once they chose one, she imported her drawing into Procreate, an iPad app. Using an Apple Pencil, she refined the drawing, added colors that matched the paints she planned to use, and layered it onto a photo of the building.

“One of the main things I love about mural painting is it’s so in your body. It’s so cheesy but it’s true: You become the tool. You’re the brush.”

McCarthy expects her art to evolve once she begins to paint. “I always have to leave room for it to breathe—I never make things exactly as they look [in the sketch],” she says. McCarthy began her mural career using brushes and rollers, but she’s since moved to fine art spray paints, which allow her to work fast and cover just about any surface. Color selection is important—she can’t mix paints as an artist with a palette might. But, she says, “there are ways to blend and overlay colors.” McCarthy uses two types of spray can caps: a skinny cap creates fine lines while the versatile New York fat cap has a broader stroke for filling and shading. It can even create a mist effect. By adjusting her finger’s pressure on the cap, the can’s angle to the surface, and the speed of her arm, she can create different visual effects on the wall.

“One of the main things I love about mural painting is it’s so in your body,” she says. “It’s so cheesy but it’s true: You become the tool. You’re the brush.”

The Many Layers of a Mural

On June 17, McCarthy unloaded her Honda Civic in front of ātac and began painting. Then, over four hot days, she transformed the façade of the firehouse.

McCarthy worked within ātac’s color palette of teals and blues, which contrasted nicely with the building’s red brick façade.

McCarthy’s gear, beyond the 22 cans of spray paint she had estimated she would need, is limited. She has an adjustable ladder and sometimes uses a piece of cardboard as a straight edge. And, she says, “A friend gave me a really nerdy muralist’s tool belt that I wear [so] I can hold six spray cans.”

“On the first day, the goal is to get ready to paint,” McCarthy says. She scrubbed the wooden doors and laid out some of her design’s straight edges with a chalk line. Then she sketched the more organic shapes with spray cans. She also used a paint roller on an extension arm to draw on the wall from a distance so she could see what she was doing.

When she returned the next morning, she began covering the doors with paint. She filled in dark background colors, then began layering on lighter shades. Over the next three days, the contours of her design took shape. Three tiered triangles extend toward the center of the building while the natural curves of leaves and grass blades spring up behind them.

McCarthy began her mural career using just brushes and rollers, but she’s since moved to fine art spray paints, which allow her to work fast and cover just about any surface.

Some muralists project their design on a wall to provide a guide, others use stencils. “I’ve never been a very exact person,” McCarthy says. “I just go for it, and if it’s wrong, I fix it. I think the organicness of my stuff lends itself to that method.”

She checks her work frequently, though, backing away from the wall and asking, “‘What did that stroke just do to the whole thing?’ It’s kind of like this dance back and forth.”

After working her way to the lighter end of the spectrum, it was time for some final flourishes. “I make some wispy lines that weave through everything,” McCarthy says. “And I do some starburst-like dots. Those are the last little highlights that make it sparkle.”

The Art of Inclusion

McCarthy’s completed mural evokes a moonlit scene. A dark sky emerges from the recesses of the doors’ arches. Grasses reflect light and bend in a gentle breeze. Delicate dandelions appear ready to release their seeds. “I’m using organic forms to convey a sensation,” she says. “I wanted it to feel like there was a light or an energy coming from within the space.”

Floral elements permeate McCarthy’s murals. “There’s a really strong male energy in graffiti, and my work can have a more feminine vibe,” she says.

Scroll through McCarthy’s Instagram account, @lenamccarthyart, and you can see why she uses the word organic to describe her work. Floral elements permeate her designs. A mural in Cambridge, Mass., features a red heart sprouting colorful leaves and branches. Female figures are also a frequent motif. “There’s a really strong male energy in graffiti, and my work can have a more feminine vibe,” she says.

Reflecting on the difference between her outdoor work and studio paintings, McCarthy says, “There’s something about public art and muralism that’s so inclusive.” No curator has chosen where to hang the painting. No museum guard stands nearby. “You’re injecting color in your neighborhood—it’s fun, it’s energy. We should live our lives surrounded by art all the time,” she says. “To me, that’s a no-brainer.”