State of Art

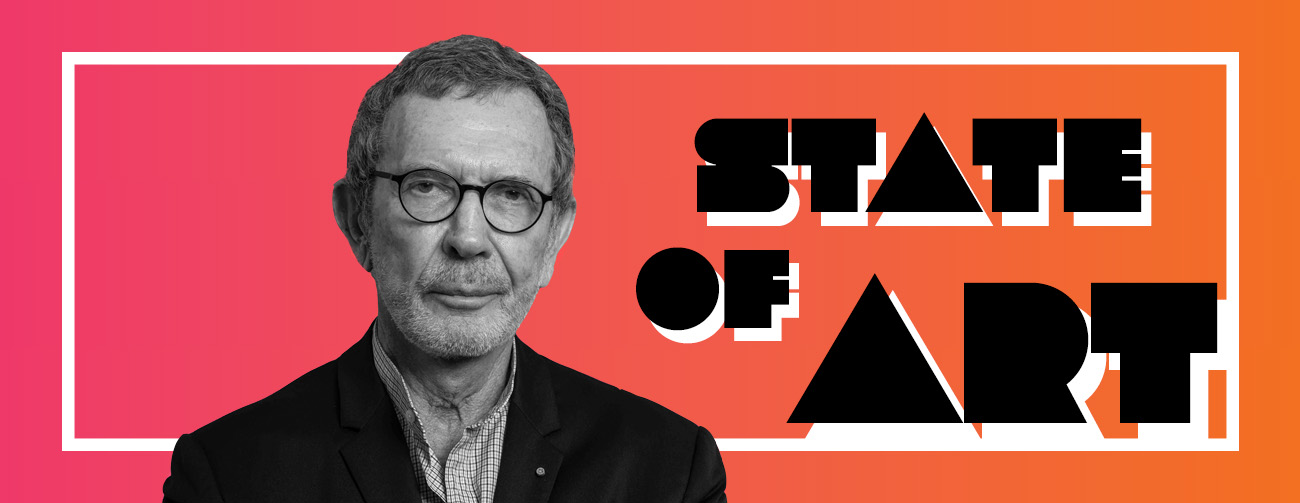

Arne Glimcher (’61) is the founder of Pace Gallery, a contemporary art gallery with locations worldwide, from New York to Hong Kong. Photo by Kevin Sturman, courtesy Pace Gallery

Art dealer Arne Glimcher on getting his start in Boston, how the art world has changed, and where he sees it headed in a postpandemic world

By Doug Most

Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace Gallery—a contemporary art gallery with locations worldwide, from New York to Hong Kong—is one of America’s most powerful art dealers. Even though it’s been almost a decade since he turned over leadership of Pace to his son, Marc, his influence on the art world remains undeniable, and his opinion is still one of the most sought after in the industry. But when it comes to reflecting on getting his start in the world of fine art, and building his Pace empire, he isn’t bashful about his time at Boston University. It was not great.

In April of 1960, while finishing his Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Massachusetts College of Art, and a few months before he would cross town to pursue his MFA at BU, Glimcher (’61) decided to open his own gallery on Newbury Street. With $2,800 from his family, he opened the space, which he named after his late father, Pace. At the start, the Pace Gallery showed the works of the only artists Glimcher knew—his art professors. In a video that Glimcher narrated in 2020 for the 60th anniversary of the Boston opening, he called it a time of “uncertainty, challenge, and hope.”

A few months after the inaugural Pace Gallery opened, Glimcher, a 21-year-old artist with big ambitions for himself and his painting, and now a fledgling business manager, arrived at CFA. He came at the beginning of a cultural revolution, as post-war optimism and abstract expressionism gave way to the pop art phenomenon characterized by the work of Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and David Hockney, among others. But at BU, he says, he felt stifled under the instruction of professors he viewed as too conservative for his own self-described “vanguard taste,” and surrounded by students averse to risk-taking.

It was, to borrow an art metaphor, like mixing oil with water. He left BU before the end of his second year, and he turned his attention to his gallery.

Sixty years later, despite his frustrating period at BU, his time here has become an integral part of his own narrative. It helped him realize what he wanted to do with his life and how to pursue it. And it certainly didn’t impede the success he would ultimately find, not only in the art world, where he’s worked with the biggest names, from Chuck Close to David Hockney to Maya Lin to Alexander Calder to Julian Schnabel (to name only a few), but in Hollywood as well. In 1988 he produced the award-winning Gorillas in the Mist, and he also developed the important, award-winning documentary, White Gold, about the ivory trade in Africa, in association with the African Environmental Film Foundation.

In a wide-ranging conversation conducted over Zoom with Glimcher, who was staying at his home in East Hampton, he held little back. He acknowledges that society, culture, and the art world have changed dramatically over his lifetime, particularly so during the last 20 years. And he’s at peace with that. “This is not my time,” he says.

But he does have opinions on where the industry that he has given his life to, and that provided him with so much, is headed.

You were born in Duluth, Minnesota, right? Can you talk about how you came to BU in the first place?

Glimcher: I was raised in Brookline, on St. Paul Street. I spent my youth at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and started to take classes there when I was eight years old. From the time I was four, I was only interested in art. In high school, I was writing English papers on Picasso’s [large, 1937 oil painting] Guernica.

My time at BU was not long, but it was important for me. I went to school with [the artist] Brice Marden (’61, Hon.’07). We were there at the same time; it developed our relationship and years later, as I became a dealer, we both got married at the same time. He married Joan Baez’s sister, and I married my wife, Milly.

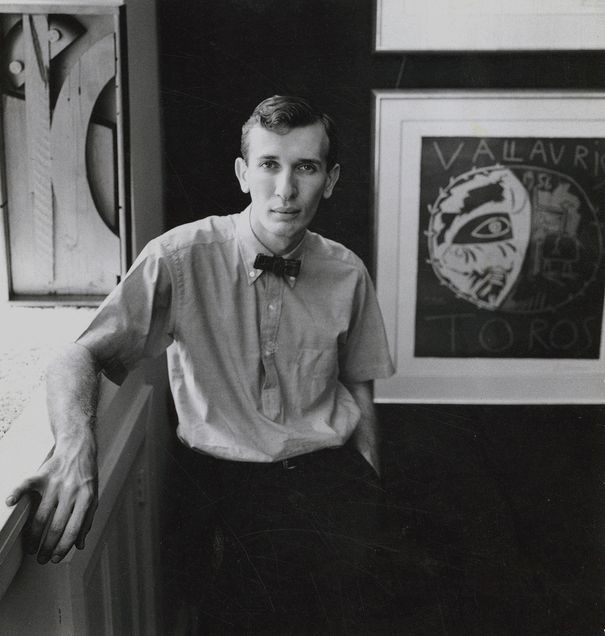

Glimcher at the Pace Gallery on Newbury Street in 1961. Courtesy Pace Gallery

Can you talk a little about your BU experience?

I came from Mass Art, a different side of the coin, where a lot of experimentation and the avant-garde was revered. At BU, figure painters were revered. Brice and I both had a lot of friction with the professors. He was not a classically talented draftsperson in life drawing classes, but his drawings were always interesting and inventive. I had more traditional ability.

And I had a studio and painted. But the students were much more conservative as well. I was a bit of a black sheep. Didn’t get along with my professors, who thought that pop artists were a hoax, but it was a good thing. Then I realized the gallery was going to be a full-time job. I was much better at recognizing art than painting at my standards. I was a very good painter. But I wasn’t good enough for me.

OK, let’s pivot and talk about artists today and where you see the art world going. It has never been easy to be a successful artist.

It’s a very good and important time for artists of color. And women. And LGBTQIA+ artists. Everything has sort of opened up in a political sense and that’s great. But I do not think that it’s opened up in any way significant in a structural sense.

What do you mean in a structural sense?

Right now, a great deal of art is heavily narrative, based on identity, race, and political movements. I think there is an important place for that. I think it’s very significant, but my focus is still on abstraction and the modernist aesthetic, which I believe can still be a narrative about the artist’s life through density and color, like Sam Gilliam’s new paintings. Conveying emotion through pure color like Rothko did. Sam Gilliam’s whole life is in his abstract paintings.

Why do you think that narrative art, as you say, based on identity and race and political movements, has taken off? Do you think in recent years, social media’s played a role in how art is seen?

I think it contributes to it. Political awareness has extended the awareness of the human condition in a personal way—ideas and emotions.

How much of that is simply a function of the last 20 years and the internet? Online sales make up just 9 percent of global art sales, according to one study. But it’s rising. Does it surprise you when people are willing to buy an expensive piece of art without seeing it in person? Would you do that?

It surprises me. I feel strongly that art needs to be experienced in person. However, having an online platform helped to connect our artists’ work with audiences during the pandemic in this past year. So it is an important platform, even if it is different than what I have experienced and known.

Does that sadden you?

It doesn’t break my heart, but it is a different way of collecting. But times change. I am a very old-fashioned man. This is not my time. It’s my son’s time, and he runs the gallery.

Glimcher with his son Marc, who is the president and CEO of Pace Gallery today. Photo by Kevin Sturman, courtesy Pace Gallery

Let’s talk about museums. Very few, with some exceptions like the Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, have large endowments to help them survive times like this. What will the museum business look like coming out of the pandemic?

I don’t know. It’s a very dangerous moment. It’s a civic issue in many cities. Detroit [Institute of Arts] was going to sell a major part of its collection to keep its museum going. Finally the government of Michigan gave them the money they needed. There are going to have to be more rescue operations. I think Boston [Museum of Fine Arts] has a very good board, and will not let it sink.

“Museums are an integral part of the human experience; they have to survive.”

Museums are an integral part of the human experience; they have to survive. There are private museums that have opened, and that money could have gone to larger institutions to incorporate people’s collections without building a vanity museum. That’s unnecessary in the community.

Why did that start to happen? What changed?

Ego is a much greater issue for collecting now than it was. In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the coterie of collectors all knew each other and traveled the world and would go to each other’s homes and see their collections. A lot of people kept collecting, but they didn’t give to museums.

Do you have a story that helps explain this?

I remember the Tremaines [renowned art collectors Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine] owned Jasper Johns’ Three Flags, which I sold to the Whitney Museum of American Art. I knew them very well, and they gave a lot to the National Gallery. They gave 70 works, all secondary pieces. But then Emily complained they were never on view.

So I asked her, “What was your purpose in selling these things?” She said, “I don’t think museums appreciate anything that they don’t pay big money for.” She was about to sell Three Flags to a great German collector, and I told her, “You can’t let that go to Germany. It’s the quintessential American painting. It has to go to the Whitney.” I said, “If I can get you a million dollars, would you sell it to the Whitney?” She said, “Oh, sure a million would be fine.” The Whitney raised the money and bought it for a million dollars. Things changed as art got valuable. At the time, Three Flags was the most expensive painting [by a living artist] ever sold at $1 million.

What role do you think art fairs play in the art market?

Art fairs are a way to meet dealers internationally. But the bad thing for dealers is that people used to come to New York or London to see exhibitions, and they’d come two or three times a year. Now dealers think they are seeing everything at the art fairs. They are not. They are seeing one example of the artist. But it’s become a social situation, in a much broader sense, and less about the artworks.

I think that’s what’s happening. It’s the same way people buy works of art on the screen. It’s a social thing. Everything changes. I don’t worry about any of it. Art is so powerful and has such an endemic role in human culture that you can’t hurt that or stop that.

But it sounds like you do think art is suffering, that it’s become more about a person’s narrative, their own story?

I am not as interested in the artist’s life as the artist’s work. The danger with art fairs and this market is that dealers will ask their artists to create something for, say, Art Basel in Miami, because they need material to sell. I just ask the question: Is the creation of art something that comes from inspiration? Is the art fair a valid inspiration for making art? Maybe it is.

Any dissemination of art is valuable. But “any” doesn’t necessarily interest me. [French painter] Jean Dubuffet said, “Beware of the newest art, for when it arrives you won’t recognize it as art.” Great art that broke boundaries was always in advance of the general public’s perception.

Glimcher speaks to the French painter Jean Dubuffet. Courtesy Pace Gallery

Have you seen anything lately that excites you?

For me, all the newest art in general, with some exceptions, I have seen it all already. I go from gallery to gallery, and I see some wonderful things, but I want to be astonished and that’s rare. Greatness is rare.

What would astonish you?

I have no idea. That’s why it would astonish me. Something totally beyond my expectation. I have seen that a few times in my life, and it’s really thrilling.

Do you think you’ll experience that again?

I hope so. I will never stop looking.