“Life Altering”

Amy Sherald’s oil painting She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them (2018).

A Stone Gallery exhibition explores race and racism, identity, and inequity of wealth and power

By Mara Sassoon | Photos by Cydney Scott

The exhibition Life Altering: Selections from a Kansas City Collection, on view at the Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery this past January and February, featured 23 striking works by women, people of color, and artists working internationally. The pieces explored such themes as identity, race, the experience of diaspora, and the impact of technology.

Among the works was New Jersey–based artist Amy Sherald’s oil painting She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them (2018)—the title a reference to a passage in the Zora Neale Hurston novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. In it, a woman with a stoic expression, wearing a bright orange cloche hat, teal shirt, and white floral-patterned pants, faces forward. She is set against a plain coral red background and meets the viewers’ gaze. Sherald has given much attention to the woman’s outfit, capturing the seeming heaviness of the large multistrand pearl necklace she’s wearing. The title of the work pairs with this intense focus given to the woman’s appearance—the viewer is privy only to what they see on the “outside.”

First Lady Michelle Obama selected Sherald to paint her official White House portrait. The painter is also known for her striking portrait of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman fatally shot by white police officers at her home in Louisville, Ky., in 2020. The image was featured on the cover of the September 2020 issue of Vanity Fair. Sherald renders all of her subjects in grisaille—a grayish monochrome—often set against solid color backgrounds, like the painting that was in the Stone Gallery show.

“The story of why I paint my figures gray has evolved over the years. I’m not trying to take race out of the conversation, I’m just trying to highlight an interiority,” she said in a conversation with fellow artist Tyler Mitchell for Art in America in 2021. “In hindsight, I realize that I was avoiding painting people into a corner, where they’d have to exist in some universal way. I don’t want the conversation around my work to be solely about identity.”

Visitors to the Stone Gallery exhibition take in Ethiopian artist Elias Sime’s Tightrope, Familiar Yet Complex 1.

All of the exhibition’s pieces were from the collection of Kansas City art collectors Bill and Christy Gautreaux, who have set out to acquire work by diverse artists. Bill Gautreaux says that collecting these works has been part of “a journey of learning and awareness that has been life altering.” The show featured artists from all over the world and many different cultural heritages, among them Elias Sime, an Ethiopian artist based in Addis Ababa, and Vibha Galhotra, an Indian artist who lives and works in New Delhi. Lissa Cramer (MET’18), managing director of Boston University Art Galleries, worked with independent curator Leesa Fanning to put together the exhibition.

“As with every exhibition at the BU Art Galleries, this show [was] about amplifying the artists’ voices,” says Cramer. “Giving these artists space to make their statement on topics like race, power, and wealth dynamics, and LGBTQIA+ rights—through such dynamic, beautiful works—[was] a timely gift to our BU community as well as to the Boston metro area.”

Explore Life Altering in the virtual gallery walk-through.

A Bridge Between Cultures

A traditional Chinese instrument becomes a bridge between cultures

By Rich Barlow | Photo by citybrabus/Shutterstock

Wenzhuo Zhang was extremely young when she took up an extremely old musical instrument. At the impressionable age of five, Zhang (’15) attended an after-school music program in China’s Hebei province, where choosing from among the dazzling array of instruments stumped her. A kind instructor suggested, “Would you like to try the yangqin? I could teach you.”

She started lessons on the instrument, a stringed dulcimer played with bamboo beaters that dates to the 17th century. What began as a hobby has become a vocation for Zhang, who today teaches the yangqin and has performed in recitals from New York State, where she lives, to the UK. In 2008, she won the National Hammered Dulcimer Championship in Kansas.

Watch Zhang perform on the yangqin as part of the Rochester, N.Y., Memorial Art Gallery's Asian Pacific American Heritage Virtual Celebration in May 2021. Video courtesy of MAG Rochester

To Zhang, the yangqin is more than a music-maker. It’s a modern bridge-builder between different peoples, which is why she tries to pass on her mastery through teaching.

“Musical instruments are a form of cultural legacy and heritage,” she says. “Learning instruments or songs is one of the most efficient ways to learn the tradition of the cultural groups from which instruments and songs originated.” The yangqin is multiculturalism in wood and string: it was modeled on a Persian instrument and reached China through trade with the Middle East.

At 13, Zhang was admitted to Hebei’s competitive art school, which accepted only one student for each Chinese instrument every two years. After graduation, she enrolled in the prestigious National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts, then came to the US for a master’s at the State University of New York at Fredonia. She received her doctorate in music education at BU.

She teaches at SUNY Fredonia and has performed with a Chinese string and wind ensemble, Western ensembles, and Chinese folk singers, and in national and global recitals. Zhang says of her musical career: “When I think about the past, I realize that it wasn’t just my decision. It was my teachers’ decisions as well. They chose me, and I am grateful. I enjoy being a performer.”

Zhang says her studies, along with playing the yangqin, have shown her the importance of multicultural music education. She vows that she’ll “continue contributing to multicultural music education in research and practice, one of my everlasting career goals.”

Conversation: Emily Deschanel & Daria Polatin

Emily Deschanel ('98), left, and Daria Polatin (’00).

Actor Emily Deschanel and screenwriter Daria Polatin talk about collaborating on the Netflix limited series Devil in Ohio

By Mara Sassoon | Photos by Ben Trivett (Deschanel) and Patrick Strattner (Polatin)

In Daria Polatin’s debut YA thriller, Devil in Ohio, teenager Mae escapes from a satanic cult and moves in with her psychiatrist, Suzanne Mathis. Mae is supposed to live with Mathis and her family for only a few days, but her stay turns longer and longer—to the dismay of Mathis’ 15-year-old daughter, Jules. Mae starts wearing Jules’ clothes, attending her school, and dating her crush. Then, the cult attempts to get Mae back, putting the Mathis family in danger.

The 2017 book is inspired by real-life events. Polatin’s manager, producer Rachel Miller, brought the story to her attention, and she was riveted by the dynamics at play between patient and psychiatrist. “I thought, ‘I need to tell this story,’” says Polatin (’00), an accomplished playwright and screenwriter who has written for Amazon’s Hunters and Jack Ryan. She tracked down and interviewed a source closely involved in the incident and began writing. “A novel seemed like the best format to tell the story initially,” she says. “Novel writing and TV writing are very different. Novel writing can be very interior—you can really live inside the head of the character. But I always had it in the back of my mind to also adapt it for the screen one day.”

In 2019, Polatin began working on a pilot script in earnest. Later this year, Devil in Ohio, a limited series starring Emily Deschanel as Mathis, will begin streaming on Netflix. Polatin, the showrunner and executive producer, and Deschanel (’98), known for her role as forensic anthropologist Temperance “Bones” Brennan on the long-running Fox series Bones, go way back. Both studied acting at BU and quickly became friends while in the program. They reconnected over Zoom in January, just as Devil in Ohio was in postproduction, to discuss their memories of BU, what it’s like playing a man onstage, and how actors and screenwriters can work together to produce great film and TV.

Daria Polatin: Emily, remember when we were in A Tale of Two Cities together at BU?

Emily Deschanel: Yes, how could I forget? Wait, who was the British woman who directed that?

DP: It was Caroline Eves.

ED: Oh my gosh, you have a great memory. I think Caroline Eves directed that junior year Shakespeare project. Was she doing that when you were a junior?

DP: Yeah, I loved the Shakespeare project. It was basically making a new piece by taking story lines from different Shakespeare plays.

ED: Yeah, it was a Shakespeare patchwork quilt kind of thing. And I think it gave the opportunity for women to play a variety of roles. I think we probably both played men quite a bit in college…

DP: Because we’re tall! Yes, I played a lot of men in college.

ED: What men did you play?

DP: I played Guildenstern. We also adapted the book The Awakening by Kate Chopin, and I played the lead woman’s husband—walking stick and all. I can’t remember what else at the moment, but it was definitely a thing.

ED: Oh, that’s fun. Yeah, you played men more than I did. But, you’re how tall?

DP: I’m six feet.

ED: And I’m five-foot-eight. I think I was in an all-female cast in a production of Mrs. Warren’s Profession, but we all played men at some point in that. Such is the experience of a theater student.

DP: I liked it because it was almost easier to dive into something so different. I also liked playing characters with dialects or accents. It helped me embody something different.

ED: I totally agree. It’s fun to dive into a role with a different dialect or accent, or different physical qualities. I don’t get to do that as much now. I mean, I’ve done dialects, but it’s not like in college when it was like, you will play an 80-year-old man with a limp from Austria.

DP: It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period—to get to explore all different kinds of characters and play all kinds of roles without any pigeonholing or judgments. I really loved how intensive it was.

"It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period."

ED: I also loved the intensity of the program. We were in class from early in the morning through rehearsals late at night. For most of us, this was all we wanted to do. And I guess it prepared us for working in television.

DP: One hundred percent. It prepared us for 18-hour days.

ED: Except it’s a lot easier when you’re 20. Daria, you had told me that [the late CFA professor of playwriting Jon] Lipsky’s class was one thing that made you interested in writing. I want to hear what that experience was like.

DP: He had seen some of my work, and [during] my senior year at BU, he found me in the hallway and said, “You are a writer, and you need to take my playwriting class.” I enrolled, but almost dropped the class because I was so busy. I filled out my drop form and brought it to Lipsky. And I remember he said, “I’m not signing that.” I begrudgingly finished the play, an adaptation of Chekhov’s short story The Lady with the Pet Dog, turned it in, and the school ended up producing it for the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival. It won the regional contest, and then it was performed at the Kennedy Center and got published.

ED: Wow, that’s so interesting to hear. And to think if Jon Lipsky wasn’t your teacher. For the record, I took his playwriting class, and he did not tell me that I am a writer.

DP: Well, I’m glad to know he didn’t just say that to everybody and I just fell for it. [Laughs.]

ED: Do you miss acting at all?

DP: The last play I was in was an Off-Broadway production in the Summer Play Festival. I played an Italian actress/model with this great accent. It was so fun. But after that I was like, “I’m done.” I haven’t really looked back. Acting onstage made me very nervous. There’s no net—if you forget your lines, what do you do? I enjoyed it, but it gave me a lot of anxiety. Not that writing doesn’t give me a lot of anxiety.

ED: It’s funny because those kind of moments—being onstage or on set and you forget a line or someone else forgets a line, and you don’t know what to do next—they terrify the hell out of me, but they are also some of my most favorite moments in acting. It’s this crazy thrill of anything could happen. I thrive on that. I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it.

DP: Well, you’re very good at it. How did you find transitioning from mostly doing theater in school and then moving into TV and film?

ED: I didn’t have that transition some people have where they’re in New York doing theater first, even though theater was my first love. But I realized that there were so many more opportunities for me as an actor in LA. I found a manager in LA and then I started auditioning for film and TV roles. A few months later, I got my first job, a Stephen King miniseries called Rose Red. Scary stuff. I actually still use some of the script analysis things we learned at BU, and I think it’s helpful to have the background I got from BU to play different parts.

DP: The script analysis classes were so good at BU. I learned so much about storytelling and breaking down a story. I think what that gave me as a writer are the tools to know the kind of information the actor needs—the character’s motivations, backstory.

ED: Yeah, and us actors appreciate that. You can make lines work, but when you have the background to understand why you’re saying what you’re saying, it makes a huge difference. I’m thinking of our time on set. I got as much information as I could from you, both on the real story and your novel. I feel like I was always hounding you to give me more and more information. What was it like making your own book into a TV series?

DP: I have adapted other books for TV before. I worked on Jack Ryan for two seasons and the season of Castle Rock that adapted Misery and tells the Annie Wilkes backstory. But getting to adapt my own novel was so interesting. I just knew the characters and the world so intimately. For the TV version, we really wanted to go into it primarily through Suzanne’s eyes and experience the story from Suzanne’s perspective. Why does Suzanne take this girl home? Why does she want to help her?

ED: I found that fascinating too. It was really helpful that you had so much time with the characters and the story from writing the book and writing the series.

"I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it."

DP: When you’re storytelling, it’s not only about what you’re showing, it’s also about what you’re not showing. So knowing what you’re not showing is helpful and adds that extra layer to creating well-formed characters whose world you’re just happening to get a glimpse into certain parts of.

ED: That’s a good point. There are always things the audience is not seeing. That’s so interesting to think about. Do you want to write another novel?

DP: I do. But novel writing is extremely time-consuming, and I’m always thinking about what medium is best for a story.

ED: A novel is no joke. I mean, not that TV writing is an easy feat in any way.

DP: It’s all very time-consuming. It just takes so much physical and mental energy when you’re really giving your all to a project. You spend years working on these things, so it has to be something that continues to bring you joy and be interesting. I first started the pilot with Netflix, like, three years ago at this point.

ED: And when did you start writing the novel?

DP: I think in 2013. The novel came out in 2017. All in all, with the show coming out, it’s been almost a 10-year process that the story has lived through.

ED: I think it’s interesting for people to understand how long some of these things can take. That’s not always the case. Most of my career was in network series. So it was grind, grind, grind. Sometimes I’d finish an episode and it would air, like, two weeks later.

DP: Oh wow! One of the advantages to writing a show for a streaming service is that usually you will finish writing the season before you film it. Of course, there are always things that you learn on set, and you still have to pivot for all the production issues, like weather…

ED: Weather? What? [Laughs.] Yeah, we definitely had to deal with our share of weather in Vancouver while shooting Devil in Ohio. Some bomb cyclones, atmospheric rivers…

DP: Snowstorms.

ED: That was nerve-racking when it snowed because it wasn’t going to match what had already been shot, and there were these consecutive things that we had to shoot.

DP: Yeah, we had to heat blast an entire field to get rid of the snow. It was a fast shoot.

ED: It was so great to have this shorthand with you on set, Daria. It was like, okay, we know each other. Let’s just dive into the work part.

DP: And you brought such a beautiful, intense focus to this role, and really graceful empathy to this character.

ED: Thank you. That’s very kind. It was really lovely to work together after so many years in such a different way than doing A Tale of Two Cities at BU.

DP: We’ve come a long way since A Tale of Two Cities.

Broadway is Back

As casts and crews return to the stage, many productions want to flip the scripts—to right systemic wrongs

By Mara Sassoon | Photo by Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Walk around Manhattan’s Theater District these days and it may seem as though nothing has changed since the pandemic forced Broadway to go dark for 18 months beginning in March 2020. In the afternoon, a line of people hoping to snag discount tickets to a show snakes around the TKTS booth and its iconic red steps in the heart of Times Square. That evening, a throng of eager theatergoers waits to be let into the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre to see the Tony Award–winning singer and actor Patti Lupone in the revival of Company.

But look a little closer, and it’s clear that things have changed. Many people in the TKTS line wear masks. While they no longer check for proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test as of May 2022, theater personnel at the doors of the Jacobs continue to remind everyone in line that they must wear their masks throughout the entire performance.

Still, inside the Jacobs—or any of Broadway’s 41 historic theaters during those magical minutes before the lights dim and the production starts—audience excitement is palpable. A group of friends huddles together in their seats, giddily clutching their playbills and smiling behind their masks for a quick selfie. Others take in the intricate details of the theater. More than once someone says, “I’ve missed this.”

People line up outside the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre for a performance of Company in January 2022. Until May 2022, theatergoers had to show proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test to see a Broadway production. An Rong Xu/The New York Times

Yes, things are a little different, but Broadway is back after its longest break ever. A typical season might include 30 to 40 plays and musicals—both originals and revivals—that employ almost 100,000 people locally. The 2018–2019 season brought in almost $1.83 billion and was the highest grossing season in Broadway history, according to The Broadway League.

Since September 2021, more than 30 productions have opened or reopened, including Company, Funny Girl, and The Music Man. The musical Mrs. Doubtfire, which had only a few days of Broadway previews before the shutdown, resumed previews in October 2021 and officially opened two months later, although it faced a couple of COVID-related hiatuses and an early closure.

"Jeez Louise, was it emotional. We’re performers, so we’re inclined to be perhaps a little more dramatic. But I was unprepared for the swell of emotion being up there together again."

“It’s been a wild ride,” says Brad Oscar, who played Frank Hillard, the brother of Daniel Hillard (aka Mrs. Doubtfire), in the musical. Oscar (’86), a Tony Award–nominated actor who starred as Nostradamus in the original Broadway production of Something Rotten!, spoke with CFA in December 2021, at the tail end of Mrs. Doubtfire’s first four-day hiatus following multiple positive COVID tests in the company. “It’s frustrating because we’re playing a game of stop and start,” he says. “But even through these hiccups, we are back and we’re going to get through this.”

Despite the hardships that Mrs. Doubtfire and other shows have experienced, many have characterized the pandemic-induced pause Broadway went through as a much-needed opportunity to reconsider its systemic issues, including pay parity and diversity, equity, and inclusion. In November 2021, the New York Times reported that some plays and musicals, including The Book of Mormon, The Lion King, and Hamilton, “are making script and staging changes to reflect concerns that intensified after last year’s huge wave of protests against racism and police misconduct.”

Tony Award–nominated actor Brad Oscar (’86), at left, played Frank Hillard in Mrs. Doubtfire. Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

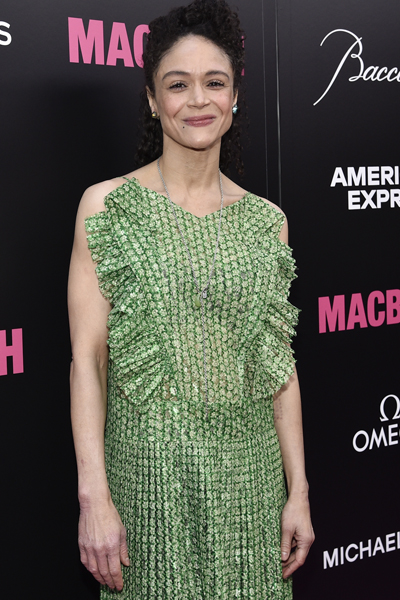

“I think it’s time the theater and film industries get with the program and realize that there are all sorts of truly brilliant actors out there who can play any role,” says Tony-winning producer Fred Zollo (CAS’75), who coproduced the Broadway revival of Macbeth, starring Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga. The production, which premiered in March 2022, is notable for its inclusive creative team and casting, including actor Amber Gray (’04) in the traditionally male role of Banquo, and the nonbinary actor Asia Kate Dillon as Malcolm. “It’s taken us a very long time—way too long,” says Zollo, “but we are finally starting to see productions taking this view.”

“It’s Gonna Be All Right”

A few weeks before Mrs. Doubtfire reopened on Broadway in December 2021, the cast appeared on Good Morning America to sing one of the show’s playful songs, “Bam! You’re Rockin’ Now.” At the end of their performance, they segued into a peppy riff on the musical’s closing number, “As Long as There Is Love.” Their words rang like a resilient battle cry: “It’s gonna be all right—as long as there is love.”

The show finally had its opening night on Broadway on December 5, 2021.

“Jeez Louise, was it emotional,” Oscar says. “We’re performers, so I think we’re inclined to be perhaps a little more dramatic. I knew I missed performing because this is such a part of who I am—it feeds my soul. But I was unprepared for the swell of emotion being up there together again.”

Watch Brad Oscar and the cast of Mrs. Doubtfire perform on Good Morning America in November 2021. Video courtesy of Independent Musicians Foundation

After it returned to Broadway, Mrs. Doubtfire followed intense COVID protocols, including working with an outside company to manage its staff testing program, and having two compliance officers at the theater each day to ensure theater staff and audiences adhered to masking, testing, and vaccination requirements. Oscar says he went to the theater every day to get tested.

Even so, not long after its short December hiatus, as Omicron cases rose, Mrs. Doubtfire’s creative team made the difficult decision to pause the show temporarily, from January 10 until April 14, 2022, promising to rehire everyone who wanted to return after that time. Lead producer Kevin McCollum told the New York Times that shutting down the production for that period would ultimately save it from running out of money. The Times reported that the show’s expenses ran close to $700,000 per week, regardless of whether performances took place. “My job is to protect the jobs long-term of those who are working on Mrs. Doubtfire, and this is the best way I can do that today,” McCollum told the Times. But by mid-May, he announced the show would have to close at the end of the month—three months early—because sales hadn’t improved enough. The musical still has plans for a month of performances in the UK in fall 2022 and a US tour beginning in late 2023.

Coming Back, Moving Forward

While Broadway shows are still contending with how to handle pandemic-related disruptions, they are also examining how to grapple with some long-standing problems. “We acknowledged that, yes we’re back, but let’s just not come back to where we were, let’s move forward,” says Oscar.

"The fact that we’re opening the door to writers, actors, and artists from everywhere—it only enriches the theater."

Even before the pandemic and the racial reckoning of 2020, the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion was a primary concern for many in the theater industry. The labor union Actors’ Equity has published a series of reports on these topics since 2017. In 2020, they released a diversity and inclusion report that looked at the demographics of its members from 2016 through 2019. In an opening letter to the report, Actors’ Equity executive director Mary McColl noted that while there had been some progress, such as more contracts being given nationally to women and people of color, “these gains have been woefully insufficient, and not uniformly true across the country.” The report found that of the total Equity contracts nationally—including principal, chorus, stage manager, and assistant stage manager contracts—63.95 percent were given to people who identify as white. “Among production contracts,” the report said, “much of the increased representation of people of color can be attributed to multiple productions of Hamilton alone.” The report also called out that “barely” one percent of contracts were given to members with disabilities.

“I think we’ve always been aware of the issues of representation in theater,” says Oscar, “but it continues to happen. And you think, ‘How does this continue to happen?’ I’m hopeful that something just broke—in a good way—and we make real change. It broke because it’s been breaking for, well, centuries.” He says Mrs. Doubtfire’s creative team made sure that the cast and crew attend a series of diversity trainings before diving into rehearsals.

Casting director Tara Rubin says that representation is at the center of every project she works on now. “It’s the first conversation we have, and it’s no longer a goal—it’s just a given,” says Rubin (CAS’77). “We didn’t do a good enough job in the past.”

Improving representation onstage begins with those who are doing the casting—a field distinctly lacking in diversity, says Rubin. “But I’d say there is an industry-wide consideration and movement toward improving that,” she says. The professional organization Casting Society of America launched a training and education program for young people who are interested in the field, with the goal of helping BIPOC students jump-start their careers. Rubin says that she and her colleagues also participate in a mentorship program with the goal of helping underrepresented groups break into the casting world. “We’re really training our eyes on how we can improve our own industry and create a viable pipeline for people.”

Oscar is upbeat about the changes he’s seen. In the two years prior to the pandemic, he performed in three regional plays that featured “the most diverse group of actors that I’ve ever worked with. I’m a white, middle-aged, Jewish gay man, but in all three of those productions, I was a minority. And I thought, ‘Isn’t that cool?’”

The Broadway revival of Macbeth is notable for its inclusive casting, including actor Amber Gray (’04), in the traditionally male role of Banquo. Greg Allen/Invision/AP

Harvey Young, dean of the College of Fine Arts, also says he’s observed “a sea change in artistic leadership [in regional theater], with more women and people of color appointed as executive or artistic directors.”

“The lineup of plays, playwrights, and productions [in regional theater] has never been more representative of the US,” says Young, a nationally recognized theater educator and a member of the College of Fellows of the American Theatre. “The single ‘diversity slot’—for a woman and/or person of color playwright—in a season has multiplied.

“What hasn’t changed, or has been slow to change, is the makeup of theater audiences,” says Young. “There is still more outreach needed to make theater accessible and affordable to more people.”

Some strides in improving accessibility of productions have been made, including presenting shows in new, experimental formats. Young points to the success of Ratatouille: The TikTok Musical and the Pulitzer Prize nomination for the online play Circle Jerk as signs that people are beginning to embrace alternate ways to attend and experience theater. Jeremy O. Harris, who wrote Slave Play, helped produce livestreamed productions of both plays.

Zollo, the producer of Macbeth, has made it a goal to improve the accessibility of his productions. The show had a Macbeth 2022 program designed to provide at least 2,022 tickets to students, with the goal of reaching students who are underrepresented on Broadway, including from BIPOC communities and those with disabilities. “We want[ed] everyone who want[ed] to see this production to have the opportunity to do so,” Zollo says.

Rubin hopes the industry continues to improve on another pressing issue: pay parity. “I would like to make sure that even though we’ve come back—and we’re all very proud of that, and it’s been incredibly hectic—that we don’t take our eyes off the big prize,” she says. “It’s time to really look at some of our financial models and pay structures for all of the departments in creating a theater production.”

Actors’ Equity, in a 2020 hiring bias report that it published in 2022, looked at the industry’s pay statistics in the three months before the pandemic shutdowns and found that “men still earn more than women on average across nearly every job category, and non-binary members tend to earn less than men or women.”

Though there is still a long way to go, Zollo, who has produced more than 100 plays and won seven Tonys in his 40-year career, says the initiatives that are being taken lately have given him hope for better inclusivity across all aspects of productions. “The fact that we’re opening the door to writers, actors, and artists from everywhere—it only enriches the theater.”

Class Notes: Spring 2022

Banner photo by Stratton McCrady

1960s

Mary Leipziger (’60) is a photojournalist. Her work can be seen in publications such as the Culver City Observer.

Carol Aronson-Shore (’63) is a professor emerita at the University of New Hampshire. She completed a series of oil paintings, Four Seasons at Strawbery Banke, in summer 2021. Her work was included in a late summer 2021 online exhibition by the Barn Gallery in Ogunquit, Maine, which featured work by artists from the Ogunquit Art Association.

Howardena Pindell (’65) showed her work in a solo exhibition, A New Language, at Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland, from November 13, 2021, through May 2, 2022. The show will move to Kettle’s Yard, the University of Cambridge’s modern and contemporary art gallery, from July through October 2022, and then to Spike Island in February 2023.

1970s

Michael Max Mosorjak (’71) showed recent oils and gouaches in an exhibition at Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, Pa., in October 2021. He is in his 43rd year as a painting conservator and has worked for numerous museums and public and private collections. He has been an instructor of art and a lecturer in conservation at several colleges and universities.

Janis Lieberman (’72) performed in concert as part of the trio Sierra Ensemble in her adopted hometown of San Francisco, Calif., in February 2022. Lieberman, a horn player, is a founding member and manager of Sierra Ensemble.

Kate Katcher (’73) wrote the comedy The Little Sisters of Littleton, about a septuagenarian sibling rivalry (one sister’s ex resurfaces and starts a relationship with the other sister). Stray Kats Theatre Company presented a staged reading of the play at the Newtown Arts Festival in September 2021 in Newtown, Conn.

Craig Lucas (’73) is a Tony-nominated playwright who wrote and directed the play Change Agent, which ran at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., from January 21 through March 6, 2022. The play imagines conversations between six of history’s most celebrated and controversial figures responsible for influencing major decisions that are still shaping our country today.

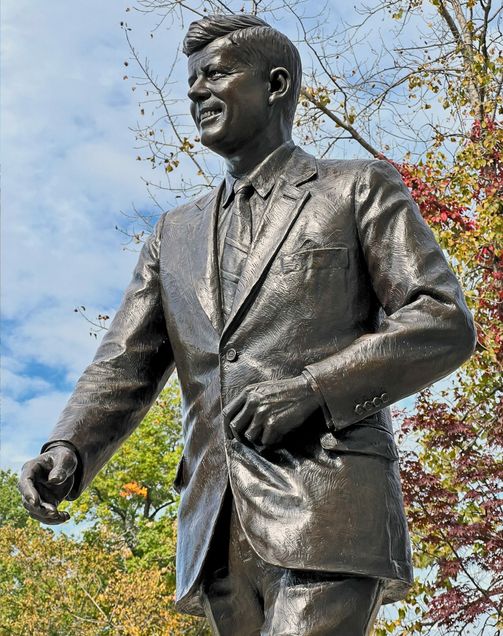

Ivan Schwartz (’73) is the founder and director of the sculpture and design firm StudioEIS, which he runs with his brother and sister. The siblings pride themselves on the extensive research behind their work—their team includes historians, sculptors, costume experts, foundry partners, and other specialists. Schwartz and his team crafted a seven-foot-tall bronze sculpture of President John F. Kennedy (Hon.’55), for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., in honor of its 50th anniversary celebration. It was unveiled in early December. StudioEIS sculptures stand in museums and public spaces across the nation, depicting historical figures including Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman.

Rick Butler (’74) has designed sets or stage lighting for the Yale Repertory Theater, Youth Concerts at the BSO, Hartman Theater Company, Stamford Center for the Arts, Classic Stage Company in New York, LaMama Experimental Theatre Club, and the Juilliard School. He has worked in the art departments of more than 50 projects for film and television, including Sleepless in Seattle, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, and The Talented Mr. Ripley. As a production designer for film and television, he has worked on Pieces of April, Person of Interest, Bored to Death, and Power Book II: Ghost. He lives on Cape Cod, Mass., and continues to work on many projects at home and abroad.

Kathleen Joy Peters (’74) and her mother, E. Loretta Ballard, were represented in the exhibition Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks, which ran from October 24, 2021, through January 23, 2022, at the Delaware Art Museum, in Wilmington, Del. The show was a remounting of an exhibition artist Percy Ricks presented at the then newly formed organization Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc. The Delaware Art Museum collaborated with Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc., to present work by most of the artists from the 1971 show, working to rehang the exhibition as accurately as possible.

Paula Plum (’75) was appointed interim artistic director of Gloucester Stage Company for 2022. Plum is a 30-year veteran of the Massachusetts theater.

Tracy Burtz (’78), a painter, is represented by Thomas Deans Fine Art in Atlanta and had a solo show there in May 2021. She is also represented by East End Gallery in Nantucket, Mass., and had her work on exhibit there during summer 2021.

Dave Wysocki (’78) performed Joni Mitchell’s legendary album Blue in honor of its 50th anniversary at the Next Stage Arts Project in Putney, Vt., in November 2021. Wysocki, a double bassist, has performed with the Vermont Symphony Orchestra, Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra, and Hanover Chamber Orchestra, as well as the Upper Valley Mozart Project and the Abendmusik Chamber Players.

Marsha Goldberg (’79) exhibited her work at ART FAIR 14C in November 2021. The exhibition had 80 booths and was held at the Glass Gallery at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, N.J.

Patricia Randell (’79) played the nurse in Nathan Darrow’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The show was a partnership with the South Orange Department of Recreation & Cultural Affairs and the Maplewood Department of Recreation & Cultural Affairs and was performed live on an outdoor stage at Floods Hill in South Orange, N.J., in July 2021.

1980s

Jason Alexander (’81, Hon.’95) reprised his role as Asher Friedman on the fourth season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, which premiered on Amazon Prime in February 2022. Alexander also played Jeff Bezos in a mock trailer for the Apple TV+ show The Problem with Jon Stewart. Alexander was featured in the Anti-Defamation League’s Concert Against Hate in December 2021.

Amy Brier (’82) had a photo of one of her Roliquery sculptures—hand-carved spheres of limestone that, when rolled in sand, leave behind patterns—featured on the cover of Paper, Teller, Diorama, an anthology of creative writing. Her most recent limestone piece, In the Time of Covid, was a collaboration with two other carvers and was installed on the grounds of Hoosier Village, a retirement community in Indianapolis, Ind. It was commissioned to honor its caregivers during the pandemic. Brier also celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Indiana Limestone Symposium, which she cofounded. She is an associate professor and chair of fine arts at Ivy Tech Community College in Bloomington, Ind.

Anthony Tommasini (’82) retired from the New York Times in December 2021 after 21 years as its chief classical music critic.

Michelle Mendez (’83,’90) retired from her career as an art teacher at Canton High School in Canton, Mass., where she taught from 2003 to 2021. Prior to that, she taught part time at Walpole High School and Newbury College.

Julianne Moore (’83) starred in Apple TV+ and A24’s Sharper and played Heidi Hansen in the film adaptation of Dear Evan Hansen. In October 2021, she appeared in Michael J. Fox’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Cure Parkinson’s comedy and music benefit show in New York. She also starred in Jesse Eisenberg’s film When You Finish Saving the World, which premiered at Sundance in January 2022, and will star alongside Natalie Portman in the upcoming drama May December.

Darryl Bayer (’84) is the artistic director and conductor of The Woodlands Symphony Orchestra in The Woodlands, Tex. The orchestra performed on July 3, 2021, at the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Pavilion’s “Stars at Night–A Salute to Service” event.

Michael Chiklis (’85) plays Red Auerbach in Adam McKay’s HBO series about the 1980s Los Angeles Lakers, Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty. Chiklis also appeared in McKay’s film Don’t Look Up, which premiered on Netflix in December 2021.

Kathy Johnson Bowles (’86) has had more than 100 works from her Veronica’s Cloths mixed media and textile series selected for publication in 49 art and literary journals across the US, including the American Journal of Poetry and the William and Mary Review. She has penned critical essays about art and has curated more than 125 exhibitions of Chinese, African, and American art. In 2021, her work was exhibited at NYC Phoenix Art, Emery Community Arts Gallery, University of Maine, Farmington, Visionary Art Collective, Art Gallery 118, and Northern Illinois University Art Museum. She is executive director of the Everhart Museum in Scranton, Pa.

Michelle Lougee (’89,’94) had her work displayed in Upsurge, too, a show about climate change and the harm humans are causing to the planet, at Storefront Art Projects in Watertown, Mass. Lougee crochets sea creatures from single-use plastic and showed a tapestry made from grocery bags in the show, which ran from September through November 2021.

1990s

Erik Blome (’92) was chosen to sculpt a statue of Dale Hawerchuk, the late Hockey Hall of Fame forward, for the Winnipeg Jets. The statue will be unveiled in True North Square in Winnipeg in August 2022.

Cindy Moore (BUTI’87, CFA’92) teaches art at Bridlewood STEM Academy in Flower Mound, Tex., and is a teacher for the Flower Mound Cultural Arts Commission. Moore formed Creatives Unite, a nonprofit through which creatives use their gifts to bring awareness to everyday issues and stand up for injustices.

Shea Justice (’93) was a featured artist in 13FOREST Gallery’s exhibition Essence: In Celebration of Juneteenth in summer 2021. The exhibit brought together 15 Boston-based artists working in diverse media to commemorate the first year in which Juneteenth was recognized as a state holiday in Massachusetts. Justice also had an exhibit at All She Wrote Books in Somerville, Mass., for Black History Month 2022.

Valerie Coleman (BUTI’89, CFA’95), an acclaimed flutist and composer, and the Philadelphia Orchestra performed her piece “Seven O’Clock Shout,” inspired by the ritual in New York City early in the pandemic of cheering for essential workers at 7 pm, at Carnegie Hall's reopening on October 6, 2021.

Paul Woodson (’95) has narrated around 300 audiobooks and over the years has received three Society of Voice Arts and Sciences Voice Arts Award nominations for audiobook narration. He received an AudioFile magazine Earphones Award in 2021 for his narration of J.W. Rinzler’s All Up.

Jennifer Elowsky-Fox (’97) and Maja Tremiszewska (’14) were pianists in the New York premiere of 24 Preludes & Fugues by American composer Larry Bell at Merkin Concert Hall in January 2022.

Joseph Conyers (BUTI’98) is director of BUTI’s Young Artists Orchestra. He served as artistic director and conductor for the Young Artists Instrumental Program’s virtual premiere of Ashé, a commission by Valerie Coleman (BUTI’89, CFA’95). Conyers is acting associate principal bass in the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Zachary Keeting (’98), who teaches at the Educational Center for the Arts in New Haven, Conn., was named one of five emerging artists to watch in the state by CT Insider in July 2021.

Michael Roberts (’98) was named executive vice president and chief marketing officer of MetLife. He previously served as chief marketing officer for the Vanguard Group’s Retail Investor Group and Bank of America’s merchant services business.

Aesop Rock (’98) collaborated with producer Blockhead for their album Garbology, which was released in November 2021.

Dana Clancy (’99) used the Sunday New York Times as canvases for the works in her project Breaking News/Broken Year. The School of Visual Arts director began the project in September 2020, painting over part or all of each chosen page with blocks of color. Clancy added portraits of people she’s Zooming with along with words—usually things those people have said. “Words written over weeks feel like a shared public space—the kind of space I’m missing and want for all of us,” she says. The project is also, in a way, part of her preparation for the September 2022 launch of a new CFA Master of Fine Arts program in visual narrative, which will integrate fine arts with sequential art storytelling practices, both written and visual.

2000s

Gregg Mozgala (’00), right, established the Apothetae, a theater company that produces works that explore the experiences of people with disabilities. Mozgala, who was born with cerebral palsy, collaborated with his former BU roommate Moritz von Stuelpnagel (’00), a Tony Award–nominated director, on Teenage Dick, a satirical retelling of Shakespeare’s Richard III, which ran at Boston’s Huntington Theatre Company this past winter. “The idea was to augment the canon and to present a wide range of work that could serve as a container for the casting of not just one but multiple characters with disabilities, and hopefully generate not only employment but conversation,” Mozgala says about forming the Apothetae. Mozgala was recently included in The Kennedy Center Next 50 list.

Akiko Fujimoto (’01) conducted the world premiere of a cello concerto called Sampson’s Walk on Air at the Vermont Symphony Orchestra (VSO) in October 2021 as one of seven candidates for the VSO’s new music director. She is music director of the Mid-Texas Symphony.

Nina Yoshida Nelsen (’01,’03), Michelle Johnson (’07), and Chelsea Basler (’11) were featured in Boston Lyric Opera’s production of Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana in October 2021.

Ian Loew (’03) started the podcast Down the Pit, which discusses the world of classical music and its future. The podcast is available on all major platforms. Please reach out to admin@downthepit.com if you’re interested in being a guest on the show.

Uzo Aduba (’05) and Edmund Donovan (’12) performed in the Broadway production Clyde’s this past winter. Clyde’s follows a truck stop sandwich shop that offers its formerly incarcerated kitchen staff a shot at redemption. Aduba is the inaugural host of Netflix Book Club, a series in which the streaming service highlights the literary properties it has adapted for the small screen. She was featured in the sports drama National Champions and will appear in Painkiller, a Netflix limited series focusing on the origins of the opioid crisis. She was nominated in the category of Best Performance by an Actress in a Television Series–Drama for her role in In Treatment at the 79th Golden Globes.

David Delmar Sentíes (’06) is founder and executive director of Resilient Coders, which trains people of color from low-income backgrounds for high-growth careers as software engineers and connects them with apprenticeships.

Autumn Ahn (’08) had her work in the exhibition Boomshakalaka at False Flag Gallery in New York, N.Y., from November 20, 2021, through January 10, 2022. In 2021, Ahn was invited for a two-month residency at Selebe Yoon Gallery, in Dakar, Senegal, and showed her work there in an exhibition, Mots de neige, histoires en sable.

John Beder (BUTI’03, CFA’08) directed the film Dying in Your Mother’s Arms, which was nominated for a News & Documentary Emmy Award in the category Outstanding Short Documentary. It was published by the New York Times as part of its Academy Award–nominated series Op-Docs. The film was also a Vimeo Staff Pick of the Month and received awards from film festivals around the country.

Heather Braun (BUTI’01,’02, CFA’08,’13) was a coach at the Danbury Music Centre’s second annual Chamber Music Intensive in August 2021. She is the first violinist of the Arneis Quartet.

Julia Noulin-Mérat (MET’06, CFA’08) was an executive producer of More Than Musical’s 90-minute opera film of La Boheme, which was made in partnership with Opera Columbus, Opera Omaha, and Tri-Cities Opera in Binghamton, N.Y. The film was shot during the pandemic and updated the story’s original themes of sickness and poverty with contemporary threads of racism and immigration. Noulin-Mérat is creative director of More Than Musical and general director and CEO of Opera Columbus.

2010s

Erik Grau (’10) and Kamal Ahmad (’16) were jurors and award judges for juried exhibits at Piano Craft Gallery in Boston, Mass., in collaboration with the Unitarian Universalist Ministry and the Newton Art Association in 2021 and 2022. Ahmad is the director and Grau is the president of the Piano Craft Gallery.

Elias Stern (’10) won two 2021 CLIO Entertainment awards for his role as creative director on a campaign for Activision and Call of Duty. Stern is an associate creative director at the agency Giant Spoon.

Zach Horn (’11) showed his work in the solo exhibition Cookout, which contemplates his spiritual relationship with food. The show was on view at GoggleWorks Center for the Arts in Reading, Pa., throughout July 2021 and at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, Mass., from September 30 through October 30, 2021.

Kyle Larson (’12) had paintings on display in summer and fall 2021 at Oklahoma Contemporary’s ArtNow 2021, which showcased the new work of artists with active studio practices in Oklahoma. Larson is an associate professor of art at Northwestern Oklahoma State University.

Louise Billaud’s (’14) article “#BeTheChange: Breaking Barriers for Sustainability in Community Bands” was featured in the fall 2021 issue of Canadian Winds, Journal of the Canadian Band Association. Billaud is a professor of music at New River Community College in Dublin, Va.

Ford Curran (’14) is a graphic designer and an archivist at BU’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center. Curran has created portraits of the last two directors of the Gotlieb Center. His artwork has been published in literary magazines, used commercially by universities and schools, and exhibited twice at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum staff exhibition.

Taylor Apostol (’15) had sculpture exhibits at Arts Worcester in Worcester, Mass., Pingree School in Hamilton, Mass., and Nearby Gallery in Newton, Mass. Apostol completed a portrait monument for poet and writer Julia Dorr with Evan Morse (’15) for the Rutland Sculpture Trail in Rutland, Vt.

Evan Morse (’15) held a dedication for a memorial he recently installed for the late Jim Blackburn, his high school track coach in Newton, Mass. He also had exhibits in Lenox, Mass., and Newton, and is participating in the Goetemann Artist Residency in Gloucester, Mass.

Jennifer Jaroslavsky (CAS’15, CFA’17,’19) performed in Seaglass Theater Company’s The Lure of the Sea, a concert of classical repertoire that highlights the relationship of fishermen and women to the sea, in August 2021.

Jay Rauch (’18) and Aaron Michael Smith (’18) are members of the Boston/Seattle experimental duo grein. They released their debut album, TAXIC GNOSIS, in December 2021. Cassette tapes can be ordered on dinzuartefacts.com/dnz70 and digital downloads can be found on grein’s Bandcamp and on other streaming services.

Malik Tricoche (’18) had a solo exhibition titled Romanticismo & Disciplina at the ICI Venice in Italy in September 2021.

Dylan Wack (’18), Emma Laird (’22), Mishka Yarovoy (’23), Makhamahle Kekana (’24), Alan Kuang (’24), and Gayane Kaligian (Pardee’22) were in the ensemble for Apollinaire Theatre Company’s production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in August 2021. The production was bilingual, with dialogue in both Spanish and English.

Elizabeth Flood (’19) was one of 20 visual arts and writing fellows in 2021–2022 at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Mass. Her paintings survey the complex layers of extraction, violence, and expression within the American landscape.

2020s

John Dally (’20) joined the College of Art and Humanities faculty at Northwest Nazarene University in Nampa, Idaho, as a professor of music and director of instrumental activities and music education.

Peter Everson (’20), a trumpet player, performed at the Peninsula Music Festival’s February Fest in 2022 in Egg Harbor, Wisc. He and his father, trumpeter Terry Everson, an associate professor of music at CFA, collaborated with other musicians to produce the works of Vivaldi, Holloway, Ketting, Hansen, Johnson, Hubeau, and Stephenson.

Anna Harris (’20) performed a violin jazz concert for Boston Public Library’s Concerts in the Courtyard Series in August 2021. Harris is a soloist, teacher, and chamber and orchestral musician, and has enjoyed performing in venues such as Benaroya Hall, Boston Symphony Hall, and the Brevard Music Center.

Charles Suggs (’20) presented work in an exhibition titled Transfixed at the VERY Gallery from December 4, 2021, through January 22, 2022. Included in the show was his “Body Stare” monotype series, in which he depicts a Black man rendered bare-chested and unblinking. On top of each image, he has made marks that allude to scars.

Michael Sundblad (’20) joined Lewis and Clark Community College in Godfrey, Ill., as dean of liberal arts, business, and IT in August 2021. His research focuses on equity in higher education.

Sam Weinberger (’21) painted a mural at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center (SEMC), Boston University’s newest teaching hospital in Brighton, Mass. The five-foot-tall, 100-foot-long mural displays portraits of healthcare workers as a tribute to frontline workers. Weinberger’s proposal was chosen by Brighton Main Streets and SEMC.

Amanda Fallon (’21), Meg McGuigan (’21), and Erica Terpening-Romeo (’21) worked on Boston Playwrights’ Theatre’s production of Lorena: A Tabloid Epic, pictured above, written by Eliana Pipes (GRS’21). Fallon was the production’s lighting designer, McGuigan was the scene designer, and Terpening-Romeo was the director. Terpening-Romeo also directed Incels and Other Myths by Ally Sass (GRS’21) at Boston Playwrights’ Theatre in December 2021.

Solar Art

Laura Blacklow blends traditional photo techniques with modern messages to create the books in her Quarantine Project

By Marc Chalufour | Photos by Conor Doherty

Blacklow prepares a solution she’ll use to coat her paper for a cyanotype.

Laura Blacklow learned photography long before the advent of digital cameras, but the Cambridge, Mass.–based artist never developed a fondness for working in a darkroom. Instead, she gravitated to processes like cyanotype and Van Dyke brown printing that she could do outdoors. “I just come alive when the sun comes out,” she says.

Those classic sun-printing methods are also conducive to experimentation. Blacklow (’67) has printed onto paper and textiles, and she’s created images with both photo negatives and three-dimensional objects. Developing the prints is often just the first step. She might color them with pastels or watercolor paints, sew them, or fold them into unique artist’s books.

Both artist and activist, Blacklow often blends words and images to convey a message in her work. She’s made prints with native rainforest plants to highlight the plunder of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala and with plastic toy soldiers to expose violence against the Maya. For the past two years, Blacklow has drawn inspiration closer to home—pulling words from her readings, objects from her home, and flowers from her garden, she has created a series of accordion-fold books that she calls her Quarantine Project.

“The Best of Multiple Art Forms”

To make a sun print, she lays the coated paper and objects she plans to print on a tray, covers them with a sheet of glass, and carries it all outside.

As a kid growing up in Washington, D.C., Blacklow followed the work of Jacqueline Bouvier, a photographer and columnist for the Washington Post before Bouvier married John F. Kennedy (Hon.’55). CFA didn’t have a darkroom when she attended, so Blacklow studied painting and drawing, then trekked down Comm Ave to take a photojournalism course at the College of Communication. A Robert Rauschenberg exhibit at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art during her senior year made a lasting impression.

“This man was combining photography with painting. I know it wasn’t journalism in the strict sense, but he was making statements about being alive,” she says. “He just knocked me out.” Blacklow began melding mediums and hasn’t stopped. More than five decades later, she still considers Rauschenberg her biggest influence—although the form that she has devoted most of her career to isn’t framed prints meant to be hung on a wall. “I’m not a person who needs to make heroic, large artwork,” she says. “I like little, intimate messages.”

To Blacklow, a book represents the best of multiple art forms. Each page can be observed alone, like a photograph or painting, while the book itself occupies three dimensions, like a sculpture. And the physical act of studying and turning the pages takes time, like viewing a film. “There’s such an intimacy there. You can hold it in your lap. You can leaf through it frontward and backwards,” she says.

The Quarantine Project

The pandemic cut Blacklow off from her usual sources of inspiration: traveling and doing deep archival research. Quarantined at home, she tended to her flower garden where she grows hibiscus, lilies, astilbe, hosta, ferns, iris, daffodils, tulips, crocus, bleeding hearts, wisteria, and cohosh. She cleaned out her grown son’s old closet and discovered a box of his high school English books and began reading, for the first time, James Baldwin, Nadine Gordimer, and James McBride.

Sometimes, she’ll use an indoor artificial exposure unit to make her prints if there is not enough sun outside.

The words of others help Blacklow process world events. “I’ve been an avid journal keeper since I was a child,” she says. “I write down quotes, I write down dreams.” With the pandemic worsening and amid the national reckoning over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, she decided to share some of the quotes she found most helpful. “It’s so hard to have hope sometimes. And I’m an optimist,” she says.

Blacklow began pairing quotes with plants from her garden or other objects found around her house, like old locks and keys, and making sun prints in her yard. Quarantine Project captures a vision of the pandemic that’s uniquely her own. Blacklow has produced more than a dozen one-of-a-kind books, drawing from sources as disparate as Native American proverbs, the late congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis (Hon.’18), 13th-century Persian poet Rumi, and contemporary Russian poet and mystery writer Elena Mikhalkova.

Each book is formed by a single sheet of folded paper that opens to reveal a print Blacklow created by laying objects and sheets of acetate, with words written on them, over light-sensitive paper.

Blacklow is quick to point out that she often employs more modern methods in her art. “I want to be really clear about this—I’m not a Luddite,” she says. When the first color Xerox machines were introduced, Blacklow printed onto the thickest paper its rollers could handle without jamming. She’s printed onto satin, which she had to stiffen with spray-on starch, experimented with Polaroid cameras, and embraced digital photography. “Spending a day in the darkroom with a red light is not my favorite thing,” says Blacklow, author of New Dimensions in Photo Processes: A Step-by-Step Manual for Alternative Techniques (Focal Press, 2018), now in its fifth printing. “What took me a day, I can do in 15 minutes with Photoshop and an inkjet printer.”

Inside her studio, she removes the objects and then rinses the paper in water to halt the cyanotype’s development process. “Cyanotype is my favorite because it’s the least fussy,” she says.

Photographers typically use paper that’s precoated with emulsion, but Blacklow likes to have more control over the surfaces she prints on. Her work begins in the renovated carriage house behind her home, where she has a studio and darkroom. If she’s making a cyanotype, she adds water to a mixture of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to create an emulsion and, with the lights dimmed, brushes it onto sheets of paper—often a high-quality cotton rag stock. Then she hangs the sheets to dry or, if she’s in a hurry, uses a hair dryer. For Van Dyke brown, the emulsion is slightly different: water, ferric ammonium citrate, silver nitrate crystal, and tartaric acid.

“I Love the Accidents”

Blacklow’s process of making a sun print is as crude as the results are delicate. She lays a sheet of coated paper and the objects she plans to print on a tray, covers them with a sheet of glass, and carries it all outside. For large prints, she arranges everything outside, shielded from the light by a tent she made by stretching black mulching plastic over a wood frame. Then she whisks away the plastic tent and watches her images develop.

"I just come alive when the sun comes out."

On her cyanotypes, the sharp contours of leaves, delicate petals, and skinny stems appear in shades of white against a deep blue background. Imagine a blueprint of a wildflower garden—cyanotype is the same process once used by architects to develop their plans. Van Dyke brown prints offer a more organic look, mixing golden yellows and browns.

When Blacklow makes a cyanotype, she may let it sit for an hour, an overexposure that creates a deep blue, as in Sonny’s Blues. The 12-panel accordion book features words from James Baldwin’s short story of the same name. Image courtesy of Blacklow

Blacklow doesn’t set a timer for her outdoor exposures, but watches them until she’s satisfied. The duration can vary greatly depending on the time of day, temperature, and cloud cover. A cyanotype may sit for an hour, a deliberate overexposure that creates a deep blue that Blacklow especially loves. She rinses the paper to halt the process: just water for a cyanotype, or a chemical fixer commonly used in photography for a Van Dyke brown. “Cyanotype is my favorite because it’s the least fussy,” she says.

Inherit the Earth, a Van Dyke brown print, uses a Native American proverb. Image courtesy of Blacklow

In Sonny’s Blues, a 12-panel accordion book, the paper is a deep blue-green, mottled with white that looks like clouds on an ominous day. Leaves seem to float in this fantastical sky. James Baldwin’s words, from a short story of the same name, flow across this scene: “The tale of how we suffer, and how we are DELIGHTED and how we may TRIUMPH is never new, it always must be HEARD…it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.”

Inherit the Earth, a Van Dyke brown print, uses a Native American proverb: “We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors. We borrow it from our children.” A cluster of flowers—stems, petals, and all—reach across the page, parallel to the words. Each is rendered in shades of yellow and brown. They look burned onto the page, which, in a way, they are.

Part of Blacklow’s continued fascination with sun printing is that she never knows exactly what she’ll end up with. “I love the accidents,” she says. She doesn’t consider photography to be an exact representation of reality. “Just the fact that the three-dimensional world is translated onto a flat surface changes what you see.”

New Master’s in Fine Arts: Print Media and Photography

A form of art Laura Blacklow has spent her life on is now an MFA program. Beginning in fall 2022, CFA will launch an MFA in print media and photography. “This is a degree that bridges these two mediums,” says Lynne Allen, a professor of printmaking and director of the new program. “Printmaking and photography have much in common, including various techniques and the ability to make multiples. Bookmaking can also be a large part of a student’s oeuvre, and we encourage experimentation. I’m excited because this allows for a wider discussion about contemporary art—and print and photo’s place within it.”

Learn about CFA's new program merging printmaking and photography practices.

Inside the Industry with Kat Irannejad

Kat Irannejad (’97) helps run a top women-owned creative agency. Portraits of Irannejad were created by illustrators Steph Ramplin (left) and Dennis Eriksson, clients of Irannejad’s.

By Emily White Holmes

The visual arts have been a big part of Kat Irannejad’s life ever since she was a young girl and discovered she loved to paint. That love of painting set her on a path to her dream role: illustration agent.

After Irannejad (’97) earned her bachelor’s degree in painting at BU and an MFA in painting and art history at Pratt Institute, she worked in arts administration at the Smithsonian American Art Museum before taking on an array of jobs: photo editor at the New York Observer, where she worked with legendary illustrators like Barry Blitt; illustrations editor for a few National Geographic books; and artist rep at a British illustration agency. During that time, she found her true passion: connecting artists with clients to help produce spectacular publications, advertisements, and products.

As an illustration agent, Irannejad calls on the skills she learned in previous jobs, as well as her early experience as a painter: “I found that it has made a difference that clients know I come from a background where I do understand all the references they make. If they say, ‘We’re looking for an artist with a Robert Longo vibe,’ I get it.” In 2013, Irannejad and fellow artist rep Kristina Snyder cofounded the illustration agency SNYDER (formerly Snyder New York).

“It brings me genuine joy finding great talent and pairing them up with the world’s best brands—getting their work in the New York Times, on book covers, seeing their work in airports, in malls, on billboards,” she says. Here, she shares a couple insights she’s learned since starting SNYDER.

Select work by Irannejad's clients. Courtesy of SNYDER and, from left, Made Up Studio for The Washington Post, Aurelia Durand, and Ben Fearnley

Unapologetically stick to your ethos.

In a largely male-dominated industry, SNYDER is a women-owned agency dedicated to supporting a diverse group of artists.

“I’m really proud of what we’ve built,” Irannejad says. “Representation really matters to us.”

Part of SNYDER’s mission involves doing pro bono work. They have paired artists with campaigns for organizations including When We All Vote, Water.org, WaterAid, the Human Rights Campaign, and The Trevor Project.

“We’re very vocal about our politics, and I think that historically has been frowned upon for companies. From our inception, it’s worked in our favor because we just are who we are, and we welcome our artists to be who they are.”

Love what you do.

Irannejad calls herself a late bloomer because it took her many years to find her passion.

“I love a Monday morning. I genuinely love what I do, and I think the artists I work with see that, and the clients do too,” she says. “When people want to buy a product because it has beautiful artwork and packaging created by one of my artists, or if they notice a TV commercial, social media campaign, or mural, and it makes them pause for a second—it brings something that is a reprieve, a visual piece of joy—I think people underestimate the power that has.”

Libby VanderPloeg, one of Irannejad's clients, created the animation Lift Each Other Up, which went viral shortly after the 2016 election.

The Music Pioneer

Mari Kimura came to BU to study violin performance and left as an innovator at the intersection of art and technology

By Joel Brown | Photos by Conor Doherty

Mari Kimura grew up outside Tokyo in a solar house, one of the first in Japan. Her father was an architecture professor and a solar energy pioneer, always experimenting, and when she was little, the 1973 oil crisis made him famous and drew TV cameras to their home.

One day, “I remember so clearly playing outside in the cold winter light with a friend, and my shadow was very long,” says Kimura (’88). “I saw the shadow of my house, and there’s this sort of arch that shouldn’t have been there. So I look up, and it’s water gushing out of the solar panels because the pipes froze and erupted. I rushed into the house to tell my father, ‘There’s water coming out of the house! You have to go up on the roof and fix it!’ I was beside myself. And to my astonishment, he ran around the house shouting, ‘Where’s my camera?’ Fixing was not his priority—he had to document it.

“I grew up like that,” says the violinist, composer, and tech innovator, smiling. “Experimenting was in my blood, in a way.”

Now a professor of music in the Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Technology program at UC Irvine’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts, she is renowned as a violinist, performing with symphonies around the world, as well as for her innovations in “subharmonics,” a special bowing technique that produces notes an octave below the violin’s lowest string. She was invited to join the faculty at UC Irvine in 2017 in large part because of her growing use of digital technology, particularly motion detectors attached to her bow hand. The feedback she gets from the sensors—metrics such as the angle and acceleration of her arm—guides her own performances or the sounds, lighting, and projections that accompany them, and drives collaborative works with other artists.

She even has her own one-woman company, Kimari LLC, to develop and market her patented motion sensor, called MUGIC® (Music/User Gesture Interface Control), worn by her students at UC Irvine and the summer Atlantic Music Festival in Maine. The Wi-Fi sensor can create sounds, change lighting, and generate and control visual effects. Kimura wears the device in a glove on her bow hand; others attach it to their instruments or to wristbands or ankle straps or anywhere else that provides relevant data. The sensor is being used at institutions such as Harvard, Juilliard, and the University of Chicago.

"Experimenting was in my blood."

“Technology works for her in the same way it has worked for great artists for thousands of years,” says John Crawford, a professor of intermedia arts at UC Irvine who’s been collaborating with Kimura since he helped recruit her to the school. “At one point, the violin she plays now was seen as cutting-edge technology. They had to not only invent it but invent methods of playing. She finds ways of adapting technology to her own creative pursuits.

“The MUGIC device is a perfect example,” Crawford says. “People have done different kinds of motion tracking before, but she has found a way to harness the capabilities of these little chips and batteries and pieces of plastic to create new forms of expression. It’s extremely influential, really interesting, and a lot of fun to work together on.”

Violinist and composer Mari Kimura developed and patented MUGIC® (Music/User Gesture Interface Control), a Wi-Fi motion sensor musicians can use to create sounds, change lighting, and generate and control visual effects.

Kimura also has intellectual roots in the culture of innovation around Boston and Cambridge. Her parents met as Fulbright Scholars on a ship coming to the US; her father, Ken-ichi Kimura, was headed to MIT, and her mother, Aiko Kimura, a social scientist focusing on women’s labor laws, to Mount Holyoke and later Radcliffe. They married in the MIT Chapel, and returned to Japan when Aiko was pregnant. Kimura was born in Tokyo.

Kimura graduated with a degree in violin performance from Toho Gakuen School of Music in Japan (which also counts former Boston Symphony Orchestra music director Seiji Ozawa among its alumni) and came to BU to earn her master’s, studying under Roman Totenberg, the late CFA professor emeritus of music and a friend of her undergraduate mentor in Japan. She went on to receive a doctorate in musical arts from Juilliard.

Kimura’s interest in the intersection of music and technology, she says, began in earnest at BU—on and off campus.

To fulfill a requirement, she took an electronic music class, in which she was the only woman, she says. Samuel Headrick, a CFA associate professor of music, composition, and music theory, introduced her to a whole new world of sounds that were then produced largely by analog synthesizers.

While studying at CFA, she rented a room on Carlton Street in Brookline, near the BU Bridge. She was drawn into the social circle of Marvin Minsky, the late MIT computer scientist and a force behind that school’s artificial intelligence and media labs, who lived nearby on Ivy Street.

“I didn’t know how famous he was or anything, but I started hanging out in his kitchen,” Kimura says. “I got exposed to all these AI people and creative minds. And he said, ‘Oh, so you’re a violinist? What are you going to do if you lose your hand? You should start composing.’ And I’m like, ‘Who is this crazy person?’”

Together, Headrick’s class and Minsky’s prodding changed the course of her career. She learned about the groundbreaking work of the late Mario Davidovsky, a professor of composition at Columbia who became known for pairing electronic sounds with acoustic chamber music. She began integrating electronic elements into her own compositions and performances. She was eventually recruited to teach at Juilliard and NYU and was a visiting researcher at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics.

Along the way, she met and married a French mathematician and computer scientist, Hervé Brönnimann, who works in the hedge fund industry. Their daughter is a psychology student at UC San Diego, and their son joined the US Army Reserve this past year after graduating from high school.

Her work bringing the MUGIC to market has led her to pursue an executive MBA at UC Irvine, and her student cohort includes several veterans who, she says, “became a support group for me, the mom, saying, ‘Day or night, you can call us.’”

Kimura says she had moments early in her career where as a woman she may have been held back by the culture of the field. A white, male, prominent professor asked someone, ‘Who programs Mari’s sounds?’ thinking I wouldn’t be able to do it myself. I don’t think it was gender prejudice. It’s more like, ‘How can a violin player program for herself?’ The friend who got asked was more upset than I was.

“I have this image in my head of myself: I’ve been doing this very unusual thing for a classically trained violinist, and I have to have this huge machete to cut through the jungle and carve out the road I want to walk on,” she says. “So I thought, if I give machetes to five other people and we do this together, then the people behind us can go further and faster. That’s why I teach.”

Banish the Butterflies

Pianist Matthew Xiong helps musicians overcome performance anxiety

By Pamela Reynolds | Illustrations by Lydia Ortiz

By the age of 11, pianist Matthew Xiong could ascend a stage, calmly survey a sea of expectant faces, and, unperturbed, skillfully sail through Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1. For Xiong (’20), playing in front of an audience was exhilarating. Then one day in his early teens, he sat down at the piano at a high-pressure national music competition in his native Australia to perform his beloved Liszt concerto.

He froze.

“I had already been in quite a few competitions by that time, so I was not unfamiliar to the pressure,” he says. “But that competition, I felt extremely nervous. I had a gigantic memory lapse onstage, and it was just unrecoverable—and extremely humiliating.”

From that point on, Xiong was plagued by a dread of performing, something he describes as a “mild form of PTSD.” He carried on with his career, but before performances he would shake uncontrollably and his diaphragm would seize up.

“I would go onstage, and I’d be like, ‘Why am I so cripplingly anxious about this when I love performing and I love playing music?’”

The search for an answer to that question has brought Xiong to where he is today—a music instructor dedicated to helping other musicians overcome potentially career-killing performance anxiety.

Matthew Xiong (’20) works to help musicians manage performance anxiety. Courtesy of Xiong

Xiong teaches at two Boston-area music schools—Talent Music Academy in Brighton and Merry Melody Music Academy in Westwood. He says that traditional advice about overcoming stage fright—practice, practice, practice or play more public concerts—doesn’t begin to account for the complex interplay of factors leading performers to quake in fear onstage. Sometimes performance anxiety can be triggered by one bad performance, like his. Other times it can be related to deeper psychological issues. Sometimes anxiety can be intense and paralyzing, akin to a panic attack, Xiong says, or it can be the racing heartbeat that many of us feel when all eyes are on us.

His assessment is backed by research in the area, says Karin S. Hendricks, an associate professor of music and chair of music education. For example, some studies have suggested that musical performance anxiety is predicted by depression and certain anxiety disorders. Culture, genetics, and even nutrition can also play a role.

“Every one of us has such a complex and unique system of experiences and influences in our lives,” says Hendricks, who coauthored Performance Anxiety Strategies: A Musician’s Guide to Managing Stage Fright (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). “It’s really not just one thing that causes performance anxiety. We have influences from parents, teachers, experiences, but then we also have our own internal processes. And these all influence us to have our own recipe for anxiety. We call it performance anxiety or stage fright, but even that means something different to every person. What may be butterflies to some people, getting them excited to go onstage and jazzed up to give a marvelous performance, can paralyze another person.”

Karin S. Hendricks, an associate professor of music and chair of music education, is the coauthor of Performance Anxiety Strategies: A Musician’s Guide to Managing Stage Fright (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). Courtesy of Hendricks

For years after that failed performance, Xiong sought advice from musical mentors about what he might do to quell his paralyzing fear. Everyone told him that he shouldn’t worry, since he’d practiced so much. Their gentle admonishment: just don’t be nervous, you’ll do fine.

“That was really easy for them to say,” he says, “but what could I actually do to not be nervous?”

It wasn’t until Xiong, who received a master’s in music performance at BU, became a music instructor that he moved closer to figuring out how to help others with performance anxiety.

“It was actually when I got into teaching that I realized I need to solve this problem because I’m seeing this in my students and they’re suffering too,” he says. “It breaks my heart. I can see how I was in those situations. It only takes one bad performance experience for them to spiral into the void.”

Xiong began intense research and came across the work of Noa Kageyama, a performance coach at Juilliard, who advocates “centering” as a way of productively channeling nervousness. He combed through studies in the areas of anxiety and sports psychology. He discovered the concept of “flooding” or desensitizing phobia patients by immersing them in anxiety-provoking situations. He knew that such a model of treatment would not translate well to the stage, where anxious musicians are likely to feel even worse after a jittery performance, thereby reinforcing their anxiety.

“It just ends up being catastrophic,” Xiong says.

Over time, he developed his own methods. Rather than desensitize students to their performance fears, he allows them to decide for themselves exactly how much pressure they are willing to put themselves under. At first, they may play only in front of Xiong. Then they might choose to add another student or two. As time passes, they might grow their audiences little by little.

“Anyone could benefit with the kind of incremental exposure that I do with my students when they feel a sense of anxiety,” says Xiong, who has developed several other strategies for conquering stage fright. (For more of them, read “Five Steps to Help Manage Performance Anxiety,” below.)