Category: Spring 2019

Pop Up Artist

This “artist you need to know” creates electric, realist paintings

(Above) Light Bright, 53 x 30 inches, Acrylic on Canvas

Sarah Stieber (’10) appeared in several publications in 2018, including: American Art Collector, BuzzFeed, Voice of San Diego, Poet Artists, and the San Diego Reader. She has exhibited paintings at galleries throughout the US, including in her pop-up gallery, Stieber Summer Gallery, in San Diego, Calif., in 2018 and 2019. In 2017, Stieber was recognized by CBS’ On Mogul as one of “15 Female Artists You Need to Know” from Miami Art Week. Follow her on Instagram at @sarahstieber.

![]()

Magic is Something You Make. Acrylic on canvas, 42 x 42 inches

Go with the Flow. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 36 inches

Possibilities. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 inches

Rain Dance. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 inches

Eyes Closed, Heart Open. Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 18 inches

Conversations Between Women

Conversations Between Women

For the 2018 exhibition A Few Conversations Between Women at BU Art Galleries, faculty selected the work of a former mentor or an alumna they advised to be presented alongside their own.

Participants included (from top left) Associate Professor of Printmaking Deborah Cornell and Jennifer Caine (’05); Marissa Graziano (’18) and Assistant Professor, Chair of Graduate Studies in Sculpture Won Ju Lim; Rebecca Ness (’15) and School of Visual Arts Director Dana Clancy (’99); and Assistant Professor of Painting Breehan James and Madeleine Bialke (’16).

Additional alumni artists included Kitty Wales (’81,’82), Sachiko Akiyama (’02), Diana Hampe (’02), Jill Grimes (’03), Jennifer Caine (’05), Julia Von Metzsch (’07,’10), Emily Manning-Mingle (’09,’10), Sarah Pater (’09), Stacy Mohammed (’10), Leeanne Maxey (’16), Carly Pickett (’16), and Kristen Mallia (’18).

Painters Angela Conant (’04), Adrienne Elise Tarver (’07), Nina Bellucci (’09), and Erika Hess (’09) engaged in a panel discussion about the exhibition, in conjunction with Alumni Weekend 2018.

As part of the exhibition A Few Conversations Between Women, BU College of Fine Arts School of Visual Arts asked BU faculty and alumni to discuss their work, their influences, and what community means to them. Episode 1 features Assistant Professor of Painting Breehan James and Madeleine Bialke (’16). College of Fine Arts

Muse

The vastness of a prairie view and a roll of blank paper gave cartoonist Nicole Hollander (’66) space to sketch her past

By Andrew Thurston | Illustration by Nicole Hollander

For more than 30 years, Nicole Hollander’s cartoons were syndicated nationwide. Every day, a fresh Sylvia strip would spill from her pen, the eponymous central character providing sharp—often biting—commentary on political and social issues. Sylvia, said Ms. Magazine in 2010, was a “feminist heroine for the ages.”

“To have a huge space, to be looking out at another huge space, that freed me up to think about the past.”

Nicole Hollander

And then in 2012, Sylvia was retired and Hollander (’66) found herself staring at a blank sheet of paper.

Freed from the pressure of daily output, Hollander took up a two-week residency at Ragdale, a nonprofit artists’ community on the edge of a 50-acre prairie in Lake Forest, Ill. She arrived with “huge rolls of really beautiful, heavy, white paper” and some charcoal—and little idea of what to do with them.

She stapled the paper to the wall of her temporary studio—a room with an old radio and expansive, pastoral view—and stepped back.

“To have a huge space, to be looking out at another huge space, that freed me up to think about the past,” says Hollander.

She started drawing a sliver of her childhood.

As a kid, Hollander lived in an apartment building in Chicago’s West Garfield Park, then not one of the city’s best neighborhoods, now one of its most dangerous. At Ragdale, Hollander sketched the archway leading to her section of the building, filling the picture with memories: her mother listening to the neighbors through a drinking glass on the floor; a police officer ready to confront her father, “who had once again decided to tear up the ticket that he was just given.”

The past continued to flow onto the paper, eventually forming Hollander’s graphic novel memoir, We Ate Wonder Bread (Fantagraphics, 2018), lauded by the Chicago Review of Books as “a hilarious, heartfelt excavation of a lost Chicago, as well as a perfect introduction to Hollander’s trademark wit and style.”

“I just started drawing,” says Hollander of capitalizing on the freedom her prairie view gave her, “and that was really the best thing to do.”

The Conversation

Actor Alfre Woodard (’74, Hon.’04) and producer John Bartnicki (BUTI’02, CFA’07) discuss their roles in the live-action remake of a Disney classic

Edited by Lara Ehrlich

Photos by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images (Woodard)

and Braden Summers (Bartnicki)

As the sun rises over the African savanna, antelopes pick up their heads and zebras paw the dusty air. From all directions, animals converge at the base of Pride Rock, where the monkey Rafiki greets the king and queen of the Pride Lands. A celebratory Zulu chant rings out as Rafiki thrusts the new lion prince, Simba, to the heavens.

This online teaser trailer for Disney’s live-action retelling of The Lion King, which comes out in July 2019, had more than 224 million views in just 24 hours. It’s easy to see why; not only is this the iconic scene from the blockbuster film, but the live-action footage is sweeping.

The Lion King is the latest in a series of Disney classics reimagined in live action (along with 2016’s The Jungle Book, 2017’s Beauty and the Beast, and 2019’s Dumbo and Aladdin). Still, it takes guts to remake the fourth-highest-grossing animated film of all time and the inspiration for a Broadway musical that’s been running for 22 years. It’s a lot to live up to—and the film’s coproducer, John Bartnicki (BUTI’02, CFA’07), knows it. He aimed to honor the original while bringing “something new to the table,” he says. “Otherwise, what’s the point?”

This online teaser trailer for Disney’s live-action retelling of The Lion King, which comes out in July 2019, had more than 224 million views in just 24 hours. Walt Disney Studios

So, what’s new about this version of The Lion King? Besides how strikingly lifelike the animals look, the film features a fresh cast, including Oscar-nominated actor Alfre Woodard (’74, Hon.’04) as Queen Sarabi, Simba’s mother. Woodard has earned acclaim and dozens of awards, including a Golden Globe and four Emmy Awards, over more than four decades for roles like Mistress Shaw in the 2013 historical drama 12 Years a Slave and Betty Applewhite on the ABC dramedy Desperate Housewives.

Bartnicki attended CFA for trumpet performance, then set his sights on Hollywood. He worked his way from postproduction assistant on movies like Iron Man to coproducer on The Jungle Book.

Bartnicki and Woodard connected by phone to talk about the joys and pressures of remaking a beloved classic, and how they breathe life into live-action characters.

Alfre Woodard: The Lion King animators have sometimes worked for years on one specific character, like bringing Sarabi to life—but at the same time they’re filming me playing Sarabi. Tell me all about how this process works, because I still think it’s magic!

John Bartnicki: I’m doing it every day and it’s still magic to me. It blows my mind how the filmmakers take the actors’ audio performances, then use that video reference to bring the animals to life. In this case, it started with pages from our screenwriter, which we tested with storyboards.

"It blows my mind how the filmmakers take the actors’ audio performances, then use that video reference to bring the animals to life.”

John Bartnicki

Then, we have a marathon recording session and use a lot of imagination to record different versions of the scene to give our editorial team some flexibility as it gets cut together. Your vocal tracks are then cut against those early animatics, and that’s such an exciting part of the process. Once that’s fleshed out, we engage the visual effects company and the animators. They take your vocal track and the video reference of your recording, and bring these computer-generated characters to life.

There’s so much an actor brings to the performance. In addition to what you put into the microphone, there are little looks and gestures that inform the animators. Our animators choose specific moments and gestures to reflect the cast members—because we hire you not only for the sound of your voice, but for everything you do to bring this character to life. I’m very curious about how you approach voiceover work.

AW: Let’s start with the training. You’re first of all getting rid of all of the regional dialect and honing neutrality so you can then study dialect, movement—all of that gives you a reservoir to call on for any role. You can use your entire being, the power of your voice, how far you can carry it, how resonant it is, your gesture, your body—everything. By the time you come to the camera, you want to put all of that in.

I don’t like when actors just stand there barely moving their mouths, barely moving their eyes, because we don’t do that in real life; we gesticulate and we move around. So that’s what you’re doing, and you bring that moment onto a canvas that is fluid. Pathos, solace, mystery, terror, beauty—all of that is possible when you paint with your voice. It’s exhilarating.

Disney’s visual effects team and animators use a voice actor’s vocal track and video reference to bring their computer-generated character to life. “I still think it’s magic,” Woodard says. © 2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved (The Lion King)

JB: You’ve been acting since you graduated from CFA—and now you’re also producing; you were executive producer on the films Clemency (2019) and Juanita (2019). Tell me how you’re using your acting career as a producer.

AW: I came out of CFA in ’74 during a time when people chose to become an engineer, a teacher, a social worker; we thought of getting a job for the rest of your life. You guys have come of age with the understanding that you can do six things—not only within your lifetime, but at once! I was just focused on being an actor.

As you go along [in this business], you realize how much you know. And it’s just like, if mom is at work and can’t get home for dinner, you don’t sit there waiting for her, you say, “I’ll cook the dinner. I know where all the food is and I know how to satisfy our palates.” That’s how I got into producing.

I’m sort of a duct tape and paperclip producer, but you’re the real deal. I could follow you around and learn a lot about producing. What led you from the trumpet to producing?

JB: Throughout my childhood and adolescence and early adulthood, playing music was everything I wanted to do. My dream job was to play in an orchestra like the LA Philharmonic, but there was sort of a reckoning when I realized that although I loved it, it wasn’t everything for me. I think if you pursue one of those purely creative fields, there’s something spiritual about it. My peers would almost get withdrawals if they couldn’t practice. I just didn’t need music to survive the way a lot of the people did.

"Pathos, solace, mystery, terror, beauty—all of that is possible when you paint with your voice. It’s exhilarating.”

Alfre Woodard

I came home to LA, and I was able to land a production assistant job, just fetching lunches and coffees and running errands. Within days, I realized that I loved it. It brought me so much joy being around all these creative people, especially in postproduction, which is where I got my start. Seeing the movie coming together, the technical nitty-gritty, the physical process of making a movie, being around recording sessions and the edit bay—everything was so exciting. I saw how producers got to be involved in everything, and I set my eyes on that goal.

I steadily worked my way from job to job in my early career doing PA work. It wasn’t until I met [The Lion King director] Jon Favreau and started working closer with him on (2010’s) Iron Man 2 that I started working a little bit closer toward the goal of producing on his films. Chef (2014) was the first film that I was able to produce with him.

AW: One thing you said that really struck me is that when you started to be around all the creative activity in filmmaking, it brought you joy—that’s always the indicator that what you’re doing is right. Walk me through how your approach to the practical mechanics of producing on a film like Chef differs from your approach on The Lion King.

JB: Chef was a small passion project that Jon wrote, and there was no big studio with a department for anything we needed. We did everything in the dirt, trying to figure out how to pull this off. Jon wrote the script, and we were very involved in the creative process of telling the story, versus a film like The Lion King that we’re fitting within a framework of the existing film and stage show. On a small movie like Chef, we were able to change anything and do whatever we wanted in service of that story.

"The Lion King is a timeless coming-of-age story that everyone can relate to, dealing with powerful myths and themes," Bartnicki says. © 2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved (The Lion King)

As a creative producer, my goal first and foremost is to help the director execute their vision for the film. Although the needs are very different for films like The Lion King and Chef, I’m still servicing the same goal and that is: How do we make this movie?

Do you see any parallels in what I’m saying to the type of producing you do?

AW: Yes, as a matter of fact. Your mind is firing on all cylinders all the time. Filmmaking is like a fellowship, a group process in which everybody is there helping that filmmaker bring their vision fully to life. I come at it from that direction.

Let me ask you this: Everybody is excited for The Lion King. It’s emblazoned upon our hearts. Like telling any story, though, you want to bring a new way of looking at it. How do you manage people’s expectations, excitement, and nostalgia?

JB: I grew up with the animated version of The Lion King. I’ll never forget being in that theater, and at the end of that stampede scene [where King Mufasa dies] I was devastated. It’s a timeless coming-of-age story that everyone can relate to, dealing with powerful myths and themes. To be involved with anything having to do with The Lion King—let alone making it again for Disney—is just a supreme honor. There are a lot of eyes on this project, but that’s why I love working with a director like Jon, who brings something new to the table. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Our technology has gotten to a point that we can make live action, with realistic lions, and bring something new to the story, while at the same time honoring the film everyone loves. How do you approach reprising Sarabi?

AW: I am accustomed to re-creating classic roles. I mean, that’s what we do. It’s like a piece of music that’s interpreted over and over, and that’s what makes it a classic. So, I don’t feel anything other than, “Woo-hoo, I get to play!”

I just wanted to say this also: My children are 25 and 27, and when the original film came out, I remember people asking, “Oh, how are they gonna feel about the stampede?” We’ve been honest with them about life from the very beginning, and the whole concept of “the circle of life” has become a tool for so many people who are in charge of young people, because it so truthfully gives answers to the head and the heart about the circle of life. People are hungry for The Lion King because of what it is—but I think people are hungry for what The Lion King can bring to our world as well.

Court Artist

Get to know Maria Molteni (’06), whose influences defy categorization

By Emily White | Photos courtesy of Maria Molteni (above: Hard in the Paint)

Maria Molteni (’06) turns community basketball courts into works of art, with vibrantly painted pavement and knitted hoops. Her work, VICE magazine says, “breathes life into neglected neighborhoods with color and whimsy.” The courts are just one example of Molteni’s work, which includes installations, giant inflatable sculptures, and immersive interactive environments. Her influences defy easy categorization: performance art, puppetry, lucid dreaming, crocheting, community sports, the sea, insect mating patterns, and countless other interests whirl through her work.

Here’s how she answered CFA’s quick-fire questions:

Moment you realized you were an artist

Around age eight, I started telling people I planned to become an artist and pro basketball player.

WISEKNAVE Fine Art Documentation for Maria Molteni during Facebook Artist in Residence Program in Boston, Mass., in 2018.

Last thing you painted

A 40-foot-long commission in the Facebook Cambridge, Mass., office called Hoop Dreams that incorporates welded basketball hoops shaped like clouds. The phrase “hoop dreams” implies that playing the game might get one out of a hard situation, into a more celebrated life. I try to get people to think about athletics as something they can be passionate about all the time, whether or not they’re professional.

What inspired you to paint basketball courts?

I’m really into public space and the democracy and anarchy of community athletics, as opposed to corrupt corporate professional athletics. Public courts are a great place to ask neighbors to re-create the game according to their own visions and values.

Tormenta en la Cancha—Storming/Storm on the Court, in El Punto/The Point neighborhood of Salem, Mass.

Where can we encounter your work right now?

A rad witchy basketball court in Salem, Mass. I try to design courts with community members, and the youth were super excited about the idea of witchcraft. I thought it’d be cool to do a different take on it, rather than the old woman on the broomstick. I was trying to think of a gender-neutral witch who is a force of nature.

What would people be surprised to learn about you?

I’m the granddaughter of competitive square dancers and strawberry farmers.

Blank spot you’d love to paint

Boston City Hall plaza or the new basketball courts going into Lower Allston [in Boston].

If you hadn’t become an artist, you would have been...

An entomologist, geologist, or monk.

Mapping an Opera

How composer Nico Muhly (BUTI’96,’97) gets from a blank page to the Met

By Andrew Thurston | Photos by Cole Saladino

A taxidermied bat. A carved stone tablet inscribed with a single “M.” A cherry-colored harmonium. A burrito. Composer Nico Muhly’s office, a soundproofed studio in New York City, is like an eclectic museum gallery. But the clutter isn’t random. Each object plays a role in fueling his creative process, allowing Muhly (BUTI’96,’97) to create the critically acclaimed operas, concertos, and albums that have earned him a reputation as, according to the Daily Beast, “one of the world’s hottest young composers.”

Two of his most recent operas, Two Boys (2010) and Marnie (2017), had their worldwide debuts at the English National Opera and their North American premieres at the Metropolitan Opera. In February 2019, Marnie, an operatic adaptation of Winston Graham’s 1961 novel, was shown in primetime on PBS’ 13th season of Great Performances at the Met.

Muhly, an artist-in-residence at BU Tanglewood Institute, is a “prodigious talent,” according to the New Yorker; he’s also a prolific one. As well as arranging for dozens of orchestras and ensembles, he’s released solo albums; worked with artists like Björk, Usher, and Grizzly Bear; and collaborated with musicians Sufjan Stevens, Bryce Dessner, and James McAlister on a solar system–inspired album the Guardian described as a “heavenly suite of songs.”

Being in demand means racking up a lot of air miles: Muhly splits his year between London and New York, but work may also take him to Hamburg, Singapore, Sydney, Los Angeles, and other cities around the globe. Muhly hasn’t bent his artistic process to suit a life spent on the road; rather, he’s molded the world to fit his preferred style of working. For extended trips, he packs his desktop computer, full-size keyboard—it must have a number pad—and portable MIDI keyboard. He prefers to stay in apartments where the tables are sturdy enough to hold all of his equipment.

“I need to have a physical space,” says Muhly. “If I’m somewhere for longer than four or five days, I put up pictures of my friends, things that are totally a-musical that I can look at when my eyes tire of the page.” He doesn’t see these objects as distraction.

“The opposite. It’s much more grounding,” says Muhly. “It’s just a way to create a sense of continuity because I travel so much.”

He also roots himself by listening to music with a score every day, even if only for five minutes. “It doesn’t matter where I am, what I’m doing; just to remind myself where I come from,” he says of connecting with his profession. “Just a little bit of grounding and listening is really important and having a dialogue in your mind with other people’s music.”

Muhly is interested in the habits of other composers, not to emulate them but as a way to “look toward someone else’s detail.” In an October 2018 diary article for the London Review of Books, Muhly wrote that what he wants to hear from other composers is “shoptalk: What kinds of pencil are you using? How are you finding this particular piece of software? Do you watch the news while you work? I find these details telling.”

When Muhly talks about his creative process with CFA magazine, the conversation is loaded with telling details: his favorite type of pen, his document storage preferences, how he maps a composition. His descriptions turn composing from an ethereal act to a tactile one.

Drawing a Map

When Muhly started composing, he’d pull notes, snippets of rhythms, from the air and throw them onto paper. Then he’d stitch all the bits together. For listeners, he says, the finished piece of music was like an unsatisfying dinner at a fancy small-plate restaurant: the morsels were delicious, but you left hungry and made a beeline for a pizza joint. “All my pieces were 55 great ideas in a row—there was no structure.”

Handwritten notes and physical organization are central to Muhly's creative process. "I still find the case--and this is absolutely generational--that when my neck is bent, looking down, I feel much more productive than when I'm looking at a screen, which feels to me like a passive exercise," he says.

Today, when he’s working on a commission, he doesn’t notch any notes until he’s mapped out the piece’s structure.

“What are the high points? What are the low points? If it’s an opera, what is the narrative of the piece?” he says. “It’s just a diagram. It almost looks like an EKG of your heart.”

Down the Rabbit Hole

A conversation with Muhly rarely stays in one place. It ambles from the “incredibly moving” blog dedicated to Old and Middle English that he adores and thinks you might too, to an “extraordinary” stone carving business in Rhode Island to his “obsession” with how to balance a whaling ban against the rights of first peoples.

So many topics pique his interest—art, history, current affairs. “I’m constantly doing things that aren’t writing music, which makes the music better.” In fact, before writing a single note, Muhly has a period of what he has called “improvisational research”: diving around the internet, printing articles and pictures, soaking up ideas.

“You go down the rabbit hole and that’s such a pleasure,” he says. “There’s an element of procrastination, which I will freely admit, but I find myself deeply productive when I’m thinking about another thing.”

In his diary for the London Review of Books, Muhly described his research as a “magical vessel full of information and possibility.” And, if it’s hard to see how the study of whaling policies can shape a cello concerto, Muhly can’t explain it either.

“This is the magic trick, right? I don’t know how it comes out, but I do know that it does,” he says. There’s no direct connection between A and B, “but it’s more like you just feel yourself expanding.”

Muhly describes his soundproofed New York office space as a luxury "that not a lot of composers have." But it's one that has contributed to a better work-life balance. His office and home have different feels: "My home is very uncluttered," he says. The studio is not messy, but "a little more populated."

Placing Furniture

With the structure in place and rabbit holes explored, says Muhly, the music flows quickly. Knowing the physical boundaries of a piece helps him figure out which notes should go where. He says it’s like deciding where to put furniture in a new apartment.

“Sometimes, it’s once you’ve marinated in the empty space long enough and you know the physical restrictions—you know how big it is, you know how wide the doors are, the things that aren’t going to change—and that’s musically structure,” he says, and then “things present themselves in this kind of magical way, and you think, ‘Oh, this is where the Welsh dresser can go.’”

In the past, Muhly would write everything out by hand, then input it into the computer where it would stay. Today, it’s a more fluid process. In his studio, his computer is hooked up to two screens—one horizontal, one vertical—two chunky speakers, and a MIDI keyboard. He’ll input the bulk of a composition using the music notation software Sibelius, then print it out and scribble on it (he prefers uni-ball pens, for those interested in the shoptalk details), repeating the process through revisions and editing.

“I still find the case—and this is absolutely generational—that when my neck is bent, looking down, I feel much more productive than when I’m looking at a screen, which feels to me like a passive exercise.”

Muhly commissioned the stone “M” that rests on his harmonium “as a memorial stone for a friend with that initial.” Talking about it sends Muhly down one of his rabbit holes—the history of stone carving; then to a local stone carving business founded in 1705; then to traveling and learning languages...

Physical Compartmentalization

Although a conversation with Muhly is freewheeling, his working process is tightly organized. Every new project gets a physical folder—always with flaps—which will become home to Muhly’s maps and research. As the composition progresses, he’ll also use the folder to store manuscripts.

He came up with the system as a student in New York at Columbia University and the Juilliard School, squeezed into a tiny dorm room.

“New York spaces you have access to are very, very small,” says Muhly. “You have to figure out how to compartmentalize your work, just physically.” As a student, he could easily grab his work and run to class; as a professional composer, he finds the folders bring a similar benefit. “When I’m at Tanglewood, I’m teaching in the afternoons, but in the mornings, I have some time to write, so I get up and I can just grab the red folder and I’m going.”

Wherever he travels in the world, the folders travel too.

Editing an Ecosystem

From the moment he prints a manuscript, Muhly is editing. Sometimes alone, sometimes with an editor, sometimes with a collaborator. With choreographer Benjamin Millepied, Muhly says, the collaboration starts with a discussion about structure over a meal, “then I go away and start sending him music. And I’ve learned from him that either he says, ‘Yes, this is great, this is perfect,’ or, ‘I need more time here or less time here.’ So that’s more of a group editing process.”

With Nicholas Wright, the librettist for Marnie, a lot of that work was done in person. The two were even editing together right up until opening night: Wright and Muhly chopped an entire scene at the last moment. When they brought Marnie from the United Kingdom to the United States, they continued tinkering, adding a short scene to close a gap in the story they felt their previous cut had exposed.

“We found it left a hole in Marnie’s trajectory—something terribly important that wasn’t dealt with in her story,” Wright told Broadway World Opera in October 2018. “It was all about Marnie’s recovery and journey from the act of violence at the hands of her husband—to make sure that was adequately dealt with.”

Every project and every collaboration is different, says Muhly. “With collaboration, you just have to see each thing as its own ecosystem.”

Nico Muhly's opera Marnie (2017) had its worldwide debut at the English National Opera and its North American premiere at the Metropolitan Opera. Metropolitan Opera

The End Product

When Marnie debuted in the US, the Met said the score was “simultaneously rooted in lyric tonality and highly innovative techniques. The work is, in a sense, a grand opera, with 18 soloists, a prominent role for the chorus, and large orchestral forces—including piano, celesta, piccolo trumpet, and offstage percussion.” Muhly has said he doesn’t read reviews—for Marnie they ran the gamut (though even the more conditional reviews had plenty of praise for Muhly). Instead, “He accepts criticism from fellow composers,” reported the Daily Beast in October 2018. By the time the reviews publish, Muhly has moved on: he typically has about three or four projects brewing at once—though always at different stages and “completely different parts of the brain."

The Real Thing

Russell Hornsby (’96) brings complexity and grace to his role in The Hate U Give

By Joel Brown | Photo by Benjo Arwas

Maverick Carter stops his SUV in front of his house and growls at his three children to “get out of the car and line up on the grass.” A confrontation with the police has ruined their family dinner out. His teenage daughter tearily blames herself for causing it by speaking up about the police shooting of a friend. In the 2018 film The Hate U Give, Maverick is an ex-con, ex-gangbanger, ex-drug slinger, a man with volatile emotions who seems ready to explode—but what he says to his children is unexpected: “Point 7 of the Black Panther 10-Point program! Stop crying and say it!”

The children gather themselves to repeat: “We want an immediate end to police brutality by any means necessary.”

Maverick leans in to tell them that some things are worth speaking up for: “Don’t ever let nobody make you be quiet!”

In most American movies, Maverick would have been absent or in jail or on the streets, says Russell Hornsby, who plays him in The Hate U Give. Maverick might come around to bicker with his wife, but he wouldn’t be much of a parent, a stereotype reflecting society’s distorted perception of black culture.

But in the film, based on Angie Thomas’ 2017 New York Times bestselling young-adult novel by the same name, Maverick is a store owner who has long steered clear of his old gang ties, a hard-edged but fully present family man determined to keep his kids safe in an America that seems hostile to their very survival.

“We’re saying now that we need to see a well-rounded image of who we are,” says Hornsby (’96). “The truth of the matter is, Maverick does exist. There are men who are felons and ex-cons who have come out and made good on their lives. And they do have families and they do have loved ones and they are present. And that’s what we needed to show.”

The 2018 film The Hate U Give is based on Angie Thomas’ 2017 New York Times bestselling young-adult novel by the same name. 20th Century Fox

Changing the conversation

For many years, a black ex-con with gang ties in an American movie was usually a powder keg certain to explode in violence; films depicting the civil rights struggle often had passive black characters menaced—and saved—by white characters. It was hard for African Americans to find their lives depicted authentically, in all their complexity, on-screen.

A change began, Hornsby says, with Spike Lee’s early films and a personal favorite, 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, directed by Carl Franklin, starring Denzel Washington and Don Cheadle. “That is one of the most authentically black films that you’ll ever see, in my opinion. We’re just living. We’re not struggling, and trying to overcome, and all this kind of sh-t. We’re just living. And you see the black world they live in, and how they talk, in their own world, where the cloud of The Man isn’t over them. That’s us, and it’s so beautiful.”

That kind of climate change may be accelerating for black filmmakers in the era of Black Lives Matter and a president seen as openly racist by many. Hornsby points to Moonlight (“beautiful and deeply honest”) and Get Out as recent films that treated black characters and black concerns authentically.

Many said the same of The Hate U Give. The movie, which was directed by George Tillman Jr. and written by the late Audrey Wells, garnered critical acclaim and honors, including the audience award at the 2018 American Film Festival and a Top 10 ranking from the African-American Film Critics Association. Hornsby’s performance earned him a best supporting actor award from that group, and enough award-season buzz that the New York Times did an interview, although an Oscar nomination didn’t materialize.

Amandla Stenberg plays Maverick’s teenage daughter, Starr, who attends an upscale, mostly white prep school and is the only witness when a white cop shoots an unarmed young black man. Her emerging activism throws her family into a maelstrom of controversy, pulling in the police, media, protestors, and the local drug lord. But instead of acting like the stereotypical hothead, Maverick stands by his daughter, even stays with her the night after the shooting, holding a bucket when she vomits, comforting her as best he can. He knows too well the aftermath of violence, but he is also a loving dad, and tells her the world needs her: “Shine your light.”

Maverick Carter (played by Russell Hornsby) explains to his young children what to do if they are ever stopped by the police. Erika Doss/Twentieth Century Fox

Drawing from life

To tap into Maverick’s complexity, Hornsby drew on his own upbringing. He grew up with a single mother in Oakland, Calif., “not always the safest and best place to live,” even though they weren’t in the toughest part of the city. When he wasn’t in school, he spent a lot of time at the Dimond Recreation Center, where a crew of older men on staff watched over the kids summer after summer.

“They were good guys, but gruff, they talked to you in a certain way that commanded respect,” he says. “They weren’t doing anything illegal, but they talked to the around-the-way cats, the drug dealers, whatever. But there were also moments when they had a different kind of compassion, when a little kid fell and scraped his knee, and they’d hold him and be like, ‘Don’t worry about it young man, we’ll clean you up and you’ll be back playing in no time.’ And then later, you’re older, and you hear them talking about how their wife’s having another baby and how are they going to pay the rent or feed this child. It humanized them.”

“In images, it’s important to strike racism a metaphorical blow, and i think that’s what maverick does. that’s what you do when you’re able to color a character in with dimension and nuance and grace notes.”

Russell Hornsby

In 1999, when he was in his mid-twenties, Hornsby played Youngblood in a production of August Wilson (Hon.’96)’s Jitney, one of a handful of the playwright’s works he has performed in. The other actors were mostly older black men with families and money problems and complicated personal histories. He learned as much from them offstage as on, listening to them talk about their struggles and burdens, failures and successes, how they kept going. “And I have to honor those men, because I heard their voices. Me playing Maverick, that’s me saluting them and saying thank you for helping me.”

Maverick reflects all these men, Hornsby says. “That’s why the movie is so important, because the larger part of society has not seen that image of black men. In images, it’s important to strike racism a metaphorical blow, and I think that’s what Maverick does. That’s what you do when you’re able to color a character in with dimension and nuance and grace notes.”

A deep dive into creating character

When he was a younger actor trying to make his way from the stage to Hollywood, Hornsby was mostly just thinking about getting work, but when he auditioned to play stereotypical thugs, he got rejected.

“I spoke proper English,” he says with mock regret, and Hollywood was hiring rappers for their real-life street cred. “‘No, he can’t be a ghetto guy, he’s too clean-cut, he talks clearly, he enunciates! He’s not black black, he’s just black.’”

He did get cast in 2005’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’, the 50 Cent movie, playing a henchman with gold teeth, but they cut a lot of his scenes.

Hornsby can play doctors, lawyers, and cops with the best of them, but Maverick was a responsibility as much as a role. Preparing to play him demanded a deep dive into the character. Benjo Arwas

In retrospect, the reverse stereotyping served him well by allowing him to play other things: a hospital chief resident when he was just 26, a cop with kids. In NBC’s fairy-tale-noir series Grimm, he was a tough cop helping his partner keep the peace between humanity and mythological creatures. And in February, he debuted on Fox’s Proven Innocent as a lawyer who gets series star Rachelle Lefevre out of jail after she’s wrongfully convicted of murder. They partner up to help others unjustly behind bars.

Hornsby can play doctors, lawyers, and cops with the best of them, but Maverick was a responsibility as much as a role. Preparing to play him demanded a deep dive into the character.

“I sequestered myself for a month because I wanted to imagine that solitude and confinement he had while he was in prison,” says Hornsby, who lives near Hollywood. “I asked my wife to take the kids, and she went to her mother’s for a month. My day consisted of getting up early, going to the gym, coming back and making a simple breakfast, reading and writing. I immersed myself in his world, because you have to create the character from the inside out. You write out who the character is, you write out his biography, the things he thinks about. It was taking time to walk around the city by myself and find his walk, his speech patterns. These are the details you have to get into. It’s about being honest and truthful about who he is.”

Hornsby talks with The Movie Times about how black men and black fatherhood are—and should be—portrayed on-screen. The Movie Times

It’s difficult to pull apart the threads of a performance, he says. But he offers an extraordinarily subtle example of how that preparation played out on-screen: watch Maverick walk, he says, when the family approaches the courthouse where Starr is going to testify about the police shooting. “You see the walk right there, and you see the way my hands form. They’re kind of open and they’re spread by my side. This openness. And the reason is, you’re in prison, you’re in a six-by-nine-foot cell, right? Your gait is smaller when you come out, because you’re so used to being in a confined space. So what Maverick had to do was relearn how to walk, and now there’s more freedom in the walk. He’s more expressive than he used to be, because he’s a free man. You’re in prison and you lose yourself because you’re confined, and you’ve got to find yourself again.”

Other roles have also required Hornsby to do the deep dive, like Lyons, the son of Denzel Washington’s character in the 2016 film adaptation of Wilson’s Fences, or grieving father Isaiah Butler in the well-received 2018 miniseries Seven Seconds. That preparation means that once he gets to the set he’s ready to work, to “drop in” to the character. “You get into the makeup trailer and then, boom.”

“I immersed myself in his world, because you have to create the character from the inside out.”

He’s gotten the best notices of his career in these parts. But film industry kudos aren’t what motivates him. “If you are waiting for somebody else to validate you, you are going to be waiting a long time,” he says. “I have had an objective career in a subjective industry, you can’t deny that, so just in that alone I am victorious.”

With Proven Innocent soon to finish shooting, he says, “I get to go back and sow some more work; 2017 was planting season and ’18 was the harvest, and now I have to go back to planting.” He’ll continue to look for roles that expand the way black men are defined on film, and he’s optimistic, to a point, that more such roles are becoming available.

“We’re no longer having our stories told or intercepted by the dominant culture,” Hornsby says. He sees The Hate U Give’s journey to the big screen as a turning point: in the past, a book by a black woman about her experiences and culture would not have been adapted “truthfully and honestly,” he says. “I think we’re having a renaissance in that people are having an opportunity to tell their stories in their way authentically.”

Saving the Classical Music Ecosystem

How music criticism and classical music adapt with the times to remain relevant

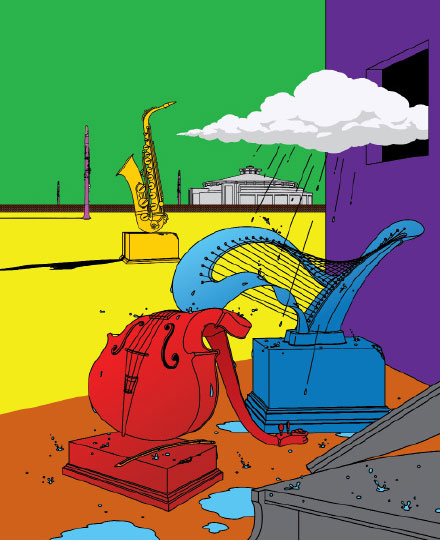

By Lara Ehrlich | Illustrations by Edward Carvalho-Monaghan

On November 14, 1943, Leonard Bernstein, then just 25, stepped in at the last minute to cover for the New York Philharmonic’s ailing conductor at Carnegie Hall. The concert was broadcast live on radio to millions of listeners, and was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. “Mr. Bernstein [Hon.’83] advanced to the podium with the unfeigned eagerness and communicative emotion of his years,” the Times critic wrote. Bernstein’s philharmonic debut was news, and the review catapulted him to fame.

In Bernstein’s day, classical music received almost as much coverage as professional sports. That was true into the late ’70s and ’80s, says Tony Beadle (’74), executive director of Rockport Music, who was performing double bass with the Boston Symphony at the time. “When you opened the Boston Globe on a Monday morning, three critics covered a lot of music in long articles, and their reactions were important to musicians,” he says.

Now, readers would be hard-pressed to find those stories in the popular press. Papers are trimming costs to compensate for plummeting profits, a trend that began in the ’80s. The arts section took the greatest hit, with classical music criticism as the first casualty.

Opera producer Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94); Anthony Tommasini (’82), the chief classical music critic for the New York Times; and Tony Beadle (’74), executive director of Rockport Music. Michal Fattal (Morrison); Earl Wilson/the New York Times (Tommasini); Courtesy of Tony Beadle

The decline of classical music’s visibility in the mainstream media is a blow to an art that’s struggling to draw audiences. Attendance, already lagging behind that of other performing arts, has been declining for decades. The National Endowment for the Arts reports 11.6 percent of adults in the United States attended a classical music performance in 2002. By 2017, that number had dropped to 8.6 percent.

CFA spoke to three experts—Beadle, Anthony Tommasini (’82), the chief classical music critic for the New York Times, and Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94), an opera producer known for mounting innovative new work—about how classical music criticism is changing, how those changes are transforming classical music, and the role, and responsibility, of the contemporary critic.

Slipping out of the mainstream

In the three years following the Great Recession of 2008, half of the arts journalism jobs in the US disappeared. And they’re not coming back. As newspapers have slimmed and folded, specialized art critics—those who cover genres like dance, theater, and classical music—have become arts generalists, been laid off, or moved to different beats. (In 2016, the San Jose Mercury News scrapped its classical music coverage and consigned its critic to covering real estate.) Only a very few specialists remain, and of those, “I can count the number of full-time classical music critics on both hands,” Douglas McLennan, the editor of ArtsJournal, told San Francisco Classical Voice.

Tommasini is one of these rarities. A trained pianist, he performed and taught music until switching to journalism; he’s been the chief classical music critic at the New York Times since 2000 and has written four books on music. With so few experts in classical music criticism, Tommasini and his handful of peers have become the voices of authority on the genre.

But they can’t possibly cover every concert or every new piece of music—and the choice of what to cover is constrained by the need to attract readers in an industry obsessed with clickbait.

“Reviews of concerts are minimal,” says Beadle. “Critics just don’t have the space and the time to write about a concert’s complexities, as they might have at one time.”

“I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.”

Beth Morrison

“This has done a terrible disservice to the classical music industry,” says Morrison, one of the most sought-after producers in the opera world and founder of the indie opera company Beth Morrison Projects. Morrison collaborates with composers to develop new works: she assembles the creative team; works with the artists to identify and implement the creative vision for the piece; secures the world premiere venue, funding, marketing, and publicity; and develops the pitch materials. Critical coverage of her projects is vital to their success and longevity, she says. “I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.”

It’s not just the word count that’s crippling classical music, says Beadle, who considers the biggest loss to be “articles about music in the mainstream; that’s what criticism was. Those reviewers brought not only last night’s concert to readers, but also the world of the musician and what they’re doing artistically.”

Amid the cutbacks, amateur critics have stepped in, putting more of an onus on readers to vet their sources. “You can find bloggers and critics writing on internet sites who are astute, informed, lively, and fair-minded, and you can find opinionated, untrustworthy know-it-alls,” Tommasini says. “Established journals and newspapers vouch for their critics and reporters and hold them to high standards. The internet challenges users in all fields to make their own determinations about the reliability of the voices they read.”

Beadle points to one internet source he finds reliable, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, billed as “a virtual journal and essential blog of the classical music scene in greater Boston” that features contributions from 80 musicians, composers, academics, and music aficionados.

“It’s harkening to the old days because writers have plenty of space” to take on the complexities of classical music, Beadle says. This kind of journalism is “a 21st-century answer to what has happened in classical music criticism.”

In this new wave of nonprofessional critics, Tommasini believes his voice is not only still relevant, but that “it matters more and more. When there’s so much chatter and so much writing out there about the arts, a trustworthy voice at a place like the Times cuts through.”

As newspapers have slimmed and folded, specialized art critics—those who cover genres like dance, theater, and classical music—have become arts generalists, been laid off, or moved to different beats. Now, “reviews of concerts are minimal,” says Beadle. “Critics just don’t have the space and the time to write about a concert’s complexities, as they might have at one time.”

He does his part to keep pace with a changing industry by incorporating multimedia to keep his readers engaged. In a 2017 review of Trinity Wall Street’s concert in honor of composer Lou Harrison, Tommasini included Spotify links to musical elements he wanted readers to appreciate; for instance, how “the slow second movement, a Siciliana in the form of a double canon, unfolds in skillfully written counterpoint. Yet the lines creep up and down and overlap with impish freedom.” Or, how “the aptly named Stampede movement races along like some combination of Asian dance and American hoedown.” Thanks to the web, readers can listen to 30-second snippets and hear for themselves what the critic is enthusing about.

Tommasini also embeds YouTube footage of concerts in his reviews, and films his own educational videos. He’s not alone in using the internet to his advantage; his fellow critics are also changing with the times to keep—and build—their readerships. Alex Ross, longtime music critic for the New Yorker, supplements his print criticism with his popular blog, The Rest Is Noise, in which he posts photos, videos, and music clips with brief commentary.

Tommasini doesn’t see the internet as a competitor, but as a complement to his work. The print and digital versions of the New York Times “go together,” he says. “You can read something on one or the other and have a rich experience, but ideally you look at both. That’s opened up all sorts of possibilities while also introducing challenges. It’s changed the way we do arts criticism.”

Tommasini still employs old-school techniques, like evocative writing, to engage readers as diverse as scholars, conductors, musicians—and people who’ve never seen a classical musical performance. He writes about music in a way that the general reader can understand, a tricky enterprise that some other beat writers don’t face. “The typical crowd at Yankee Stadium knows more insider information about baseball than the typical audience at the New York Philharmonic,” he says. “I envy sports writers tremendously for all the knowledge that they can assume their readers have.”

Plus, as he points out, “it’s very hard to describe sound in words. We have this handy technical language to do that, but only musicians know it. I can’t just use a term like chromatic harmony without losing readers.” His talent for describing music in vivid and accessible language is part of what has earned him a reputation for being “entertaining, highly enthusiastic, and very knowledgeable,” says Kirkus Reviews, “he’s the perfect guide.”

About a performance of Sibelius’ Fourth Symphony, Tommasini wrote that the second movement “sounds like a fractured dance in which the broken parts have been reassembled, but in the wrong way.” About a Leonard Bernstein performance of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring”: the opening solo melody “slowly instigated a restless tangle of squirrelly lines that became a needling, nasal-toned free-for-all.” The goal is not just to engage readers, but to turn them into listeners.

“It’s complicated, because on the one hand, I’m here to inform people about music—but I also want people, especially young newcomers, to take a chance on a concert,” he says. “An opera or chamber music program is not an exam; you don’t have to take a music appreciation course first. Just go.”

The fragile ecosystem faces collapse

Despite the fact that their numbers are declining and their roles diminishing, critics still have an outsized impact, particularly when it comes to new works. “Most artists I know feel that the critics have an enormous amount of power; essentially, the power to make or break careers,” Morrison says. “At the same time, critics don’t have jobs without the artists they are hired to write about. With this interdependence comes responsibility. A media member should always be rooting for an artist’s success; without that, the ecosystem, which is already incredibly fragile, faces imminent collapse.”

Reviewing new work is “when a music critic can really matter, if a first performance is going to lead to a second, a third and a future for the piece,” Tommasini wrote in the New York Times. He takes that responsibility seriously, and he approaches new work with an open mind, suggesting that critics do a disservice to new music by coming to it with predetermined criteria for greatness.

His latest book, The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide (Penguin Press, 2018), is in part a meditation on greatness. “All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so,” he says. “We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming, so greatness can get in the way. We hold up the giants and compare new composers to them.”

“All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so. We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming.”

Anthony Tommasini

“Imagine if you were teaching a short story workshop and young Franz Kafka showed up, with those very peculiar stories,” he wrote in the New York Times. “Would you chide him for some assault on language, or perhaps consider that he might be on to something strange and new and fascinating? If I err on the side of being open-minded in reviewing a new work, that’s O.K. by me.”

Organizations can help keep their industry alive by embracing new work, he says. That’s not such an easy task, as many classical music institutions are struggling to fill seats, especially in the absence of reviews that once sparked public excitement and spurred ticket sales, Beadle says. “They have to rethink their strategies.”

Musicians and orchestras are doing just that, by performing in nontraditional venues (the San Francisco Symphony hosts SoundBox, a concert series in a warehouse), experimenting with technology (the Boston Symphony Orchestra is loaning patrons iPads programmed with information about the performances), and adjusting ticket prices (the Cleveland Orchestra allows students to attend as many concerts as they’d like for $50 a season).

And many schools, like the School of Music at CFA, encourage musicians to seek creative ways to pursue their passion. For instance, CFA hosts an annual career development workshop series, which includes presentations on issues like freelancing, taxes for artists, financial literacy, and developing an online presence. Courses like Cultural Entrepreneurship and the Creative Economy and Social Impact promote entrepreneurship, and a minor in arts leadership gives students the opportunity to further develop their expertise.

Beadle believes classical music still holds plenty of promise. At music schools like Boston University Tanglewood Institute, he says, “you will see hundreds of kids playing classical instruments. And all the music schools are filled with students who want to play their instrument and excel at it.”

Those artists give critics something to write about—and ensure the relevance of music criticism. “Not only do artists contribute to the cultural and social richness of their community,” Tommasini wrote in the Times, “they make news. . . . A review is both an opinion column and a news report.

“But the most astute and simple defense of the role of the critic I know of came from (no surprise here) Virgil Thomson, [a composer-critic who] wrote that while traveling in Spain he was fascinated to see that it always took at least three children to play at bullfighting. One to be the bull, another to be the toreador, and a third to watch and shout ‘Olé!’ Music criticism is like that.”

Art at the Heart of BU

Artists work with unexpected canvases throughout campus

By Emily White

Photos by Bob O'Connor and Cydney Scott (Blue-Green Brainbow)

Sculptures, paintings, and multimedia works appear on walls, in windows, and along running tracks all across Boston University’s campus. Many are site-specific pieces, designed by artists who draw inspiration from the location and the surrounding environment and communities. Each site offers unique and often irregular canvases.

At BU a spectrum of academics, research, and technologies informs and inspires compelling site-specific artwork from a broad range of artists, including students and alumni. CFA professor of art Hugh O’Donnell and his students look for ways to bring together seemingly disparate areas of study: coding and sculpture, painting and fitness, biochemistry and printmaking.

“When combined with technology, art can do more than provide entertainment; it can rebuild and reanimate society,” says O’Donnell.

Featured here are six artworks either created by CFA students, alums, and faculty, or commissioned for the University—and where to find them.

Angular shapes layered with soothing gradients evoke a colossal, colorful stained-glass window in this mural on the wall of CFA’s parking lot at 855 Commonwealth Ave. Designed by Alexander Golob (’16), the mural conjures BU scenes, from the Citgo sign to Marsh Chapel. Golob was recently commissioned to install artwork expressing Innovate@BU’s vision statement in the University’s BUild Lab Student Innovation Center.

In 2017, sculptor and printmaker Carson Fox debuted her jaw-dropping 230-square-foot installation Blue-Green Brainbow in the lobby of the Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering at 610 Commonwealth Ave. Fox’s body of work evokes forms found in nature: coral, ice, and, in this case, neurons. Fox researched the work taking place inside the building to create an installation that referenced a pioneering neuroimaging technique—called Brainbow. The piece, which subtly morphs throughout the day as the light shifts across its many surfaces, is composed of 13,500 individually cast resin dots and took six 14-hour days to install. It captures “the beauty and wonder found in the life sciences,” Fox says.

In 2010, Rebecca Wasilewski (’07) designed a series of opaque panels for the lobby of StuVi-2 student housing. With an open-ended directive that the work should have an element of translucency, Wasilewski created hanging panes that allow light to filter through them in a soft glow, giving the effect of an inky, larger-than-life monoprint. The panels were designed for the space from the artist's print series Microscopium.

Another example of art inspired by scientific research is the luminous jellyfish by Heather Richard (’99), on the first floor of the Photonics Center at 8 St. Mary’s St. Noctiluna, which depicts a jellyfish that emits an ethereal light from a green fluorescent protein, was installed in 2000. The organic chemical reaction that produces the jellyfish’s light inspired Richard’s installation, commissioned with the challenge to create a work of art using light as a medium; the work evokes a traditional drypoint etching technique. The artwork was cut into acrylic glass, which emits light whenever it is scratched, and layered to imply a jellyfish submerged in water. Its light source comes from ultraviolet fluorescent lights positioned around the piece. At the time, BU School of Medicine professor Osamu Shimomura (Hon.’10) was studying the creature’s bioluminescent protein. Shimomura, who passed away in 2018, won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2008 for discovering the green fluorescent protein in jellyfish.

Public art at BU is integrated with the fabric of Boston. Students in CFA’s Site-Specific Art class noticed the eight sparse panels along the platforms at the BU West MBTA stop and decided to bring art to Green Line commuters. Andy Bell (’09), Seth Gadsden (’07), and Kristie Eden O’Donnell (’10) designed three projects that were installed in 2008 and 2009. In Bell’s panel for the BU West outbound stop overlooking the College of Fine Arts at 855 Commonwealth Ave., Rhett, the BU terrier, grapples with the Northeastern University husky mascot.

Josef Kristofoletti (’07) designed the vibrant mountain of sneakers, titled Sneakerman, on the wall of the indoor running track at the BU Fitness & Recreation Center when he was a painting student at CFA. Kristofoletti went on to become an artist-in-residence at CERN in Switzerland. There, he designed a three-story mural depicting the ATLAS particle detector, which is collecting data at the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

A Language of Time and Space

Sculptor Won Ju Lim draws on architecture to create futuristic, cinematic worlds

By Mara Sassoon | Photo by Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

Won Ju Lim says her work is never really complete; her multimedia installations are altered in unexpected ways whenever they move to a new place. “The architectural location—the space, the height of the ceiling, the geographic location, the lighting—these factors all make a difference,” says Lim, an assistant professor of sculpture at CFA. Mutability is essential to her work, which explores the relationships between people, objects, space, and time.

One of the pieces that has morphed as it’s been displayed in different venues is California Dreamin’ (2002/2018), which Lim created while living in Germany and feeling homesick for Los Angeles, where she grew up. The piece is comprised of more than 100 luminous plexiglass and foam-core board structures in shades of blue, green, and yellow that look like stacked Tetris pieces. Lim based the structures on floor plans from old do-it-yourself home catalogs. The installation also incorporates videos and still image projections of distinctive California scenery: palm trees, sunsets, boxy architecture.

California Dreamin’, 2002/2018. Plexiglass, foam-core board, lamps, three video projections. Exhibition view at San José Museum of Art. Photo by Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

First shown in 2002, the installation was recently acquired by the San José Museum of Art (SJMA), where it was the centerpiece of the 2018 exhibition Won Ju Lim: California Dreamin’. There, the piece took on new meaning: it had returned to its geographic roots, transforming a dreamscape influenced by homesickness into an idyllic vision of Hollywood. California Dreamin’ was installed in a vast, dimly lit room, where its structures were amassed into an island, their jewel tones picking up light from three videos projected on the gallery walls. The island motif was inspired in part by Lim’s interest in the origins of her home state’s name, which can be traced to the fantastical 1510 Spanish chivalric romance novel Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. The state was named after the book’s paradisiacal island made of gold and its ruler, Queen Calafia, Lim says.

California Dreamin’ was also heavily influenced by the style of science fiction films like Blade Runner and Metropolis. “The aesthetics of the cityscapes shown in these films are from decades ago, yet they remain futuristic; they suggest a superimposition of the future and the past, suspending the present,” Lim says. Cast in the cinematic glow of the surrounding videos, California Dreamin’ could be a set model for one of those films.

“My ambition was, and still is, to carry on my interest and knowledge in architecture without the confinements and limitations architects often confront.”

Won Ju Lim

Lim’s background in architecture is palpable in many of her works. Born in South Korea, she earned a BS in architecture from Woodbury University in Burbank, Calif., and an MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, and worked at architectural and design firms prior to becoming a studio artist.

“The issue of practicality inherent in architecture can be explored and questioned in making art,” she says. “My ambition was, and still is, to carry on my interest and knowledge in architecture without the confinements and limitations architects often confront.

“As an artist, I do not feel obligated to answer or solve practical issues concerning space, but I do feel the need to expose and explore our psychological and phenomenological relationships to space.” She does this by playing with scale, focusing on interior and exterior relationships, and considering the interactions between people and her art.

Her mixed media sculpture A Piece of Echo Park (2007), for example, which was on display in the California Dreamin’ exhibition, is a miniature topographic model of a hilly formation dotted with tiny trees and houses, contained inside a yellow plexiglass box. One side of the sculpture is covered in what looks like grass and shrubs, the other side reveals exposed plaster patchily covered in splotches of neon pink, green, and orange paint. By containing the structure in a bright yellow box, Lim places the viewer on the outside looking in at this diminutive world.

Lim’s Kiss 7 (2005) contains plexiglass models of the Los Angeles Case Study Houses (experimental homes built by renowned architects in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s) in wall-mounted boxes. Kiss 7 highlights a sense of changeability; any variation in light or human interference alters the installation.

For her current project, Aunt Clara’s Dilemma, Lim was inspired by the way characters travel through space in the television show Bewitched. She became fascinated with the way the witches in the ’60s sitcom pass through doors and walls, and is particularly intrigued by Aunt Clara, an elderly witch whose powers become increasingly erratic.

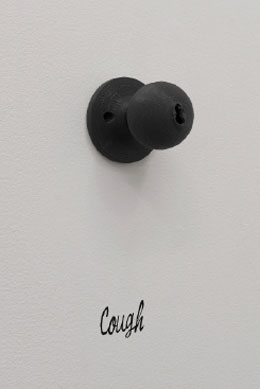

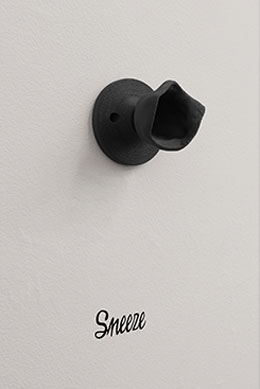

“Unable to clear the hurdle of the door, Aunt Clara becomes a fetishistic collector of doorknobs,” Lim says.

Aunt Clara’s Dilemma is composed of 3-D-printed doorknobs twisted into animated representations of bodily functions; one is evocative of a sneeze, another a cough. Lim plays off of Aunt Clara’s obsession and imbues the doorknobs with human characteristics to represent the division of space and how people move from one place to another within it.

“Space is a word that makes something of the nothing that surrounds us,” Lim says in her artist statement about the piece. “I see Aunt Clara’s Dilemma as a body of work about doorknobs, thresholds, and the moment when the old dialectic of outsides and insides becomes a mise-en-abyme,” embedding a copy of an image inside the image itself (such as a portrait of an artist holding that same portrait).

With Aunt Clara’s Dilemma, as in all of her installations, Lim says, “tangible things such as plexiglass, wood, and resin are merely vehicles that carry a specific language of time and space.”

Kiss 7, 2005. Plexiglass, lamp, shadow, 7 x 24 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

Kiss 4, 2007. Plexiglass, lamp, shadow, 7 x 60 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

Memory Palace, Terrace 49 #1, 2003. Anodized aluminum box, frosted Mylar, LED lights, mixed media sculpture, 42 x 42 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

A Piece of Echo Park, 2007. Mixed media sculpture in plexiglass box,

38 x 45 x 38 inches. Exhibition view at San José Museum of Art. Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

Cough, 2018. 3-D-printed object in styrene, vinyl lettering, 3.5 x 3 x 3 inches. DXIX Projects, Venice Beach, Calif.

Sneeze, 2018. 3-D-printed object in styrene, vinyl lettering, 3.5 x 3 x 3 inches. DXIX Projects, Venice Beach, Calif.