The Costume Engineer

Collette Livingston ensures Cirque du Soleil’s costumes withstand the performers’ complex acrobatics

Photos by Peter Tarasiuk

The Costume Engineer

Collette Livingston ensures Cirque du Soleil’s costumes withstand the performers’ complex acrobatics

There are 1,115 different costume elements in Cirque du Soleil’s LUZIA, a fantastical tour through a make-believe version of Mexico. Every night, performers morph into butterflies, snakes, birds, insects; the stage becomes a veritable Noah’s Ark—rain and all—of flamboyant creatures, large and small. And, thus transformed, the performers fly through the air, dance across the stage, and contort their bodies in unimaginable ways in a show of the company’s signature, mind-bending feats of athletic grace.

This is all to say: There’s a lot riding on those 1,115 pieces of costuming. Each one must be flexible enough to accommodate the performers’ superhuman gymnastics; durable enough to withstand repeated friction, soaking, twisting, and stretching throughout thousands of shows; and eye-popping enough to make even those in the nosebleeds sit back in awe.

Invariably, something will rip. Or pop. Or chafe. And when it does, more often than not, the performers turn to Collette Livingston, assistant head of wardrobe, for an answer.

“When it’s a two-show day, or a three-show day, you really have to prioritize what you can get done,” says Livingston (’08), who joined Cirque du Soleil shortly after graduating from BU. “We’ll organize all the costumes on the rack of repairs [backstage] by which act they appear in. And sometimes you are finishing a costume during act one for someone to wear in act two. You just need to know your timeline and how fast you think you can achieve it.”

Eye-catching—and sustainable

One costume in particular ends up on those repair racks more than any other. It may not be the flashiest—that would be the dress in LUZIA that turns from white to red as if by magic (but actually by way of 61 motorized white flowers whose red petals open up). Rather, it’s a piece with which Livingston says she has “a love-hate relationship.”

The costume shows up during a portion of the show that takes place in the jungle at night.

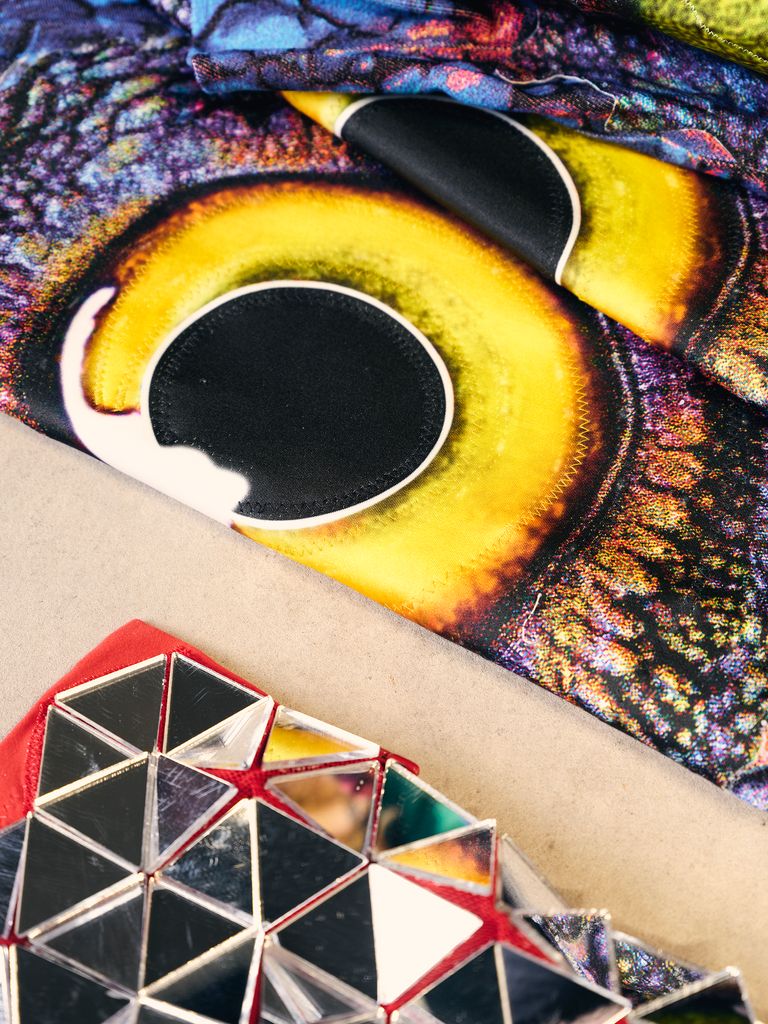

It’s a scaly, reptilian-looking set worn by performers who climb tall, thin poles onstage. Highly decorated, the costumes feature vibrant blues, oranges, and reds, but the main event is a series of crafty yellow eyes that look like they might blink at any moment. Like the spiny skin they emulate, these costumes have to be tough and protective. The performers who wear them specialize in a kind of high-flying acrobatic dance performed entirely on rubber-coated poles—a technique known as “acro-pole.” They can grip the pole not just with their hands but in the crease of their hip, or the hinges of their knees, to create gravity-defying postures.

Photo by Anne Colliard

Livingston says she has “a love-hate relationship” with the scaly, reptilian-looking costumes worn by LUZIA performers who specialize in “acro-pole,” a kind of high-flying acrobatic dance performed entirely on rubber-coated poles. The costumes—and the performers themselves—take a beating. “There’s not a day they don’t need repair,” she says.

For Livingston, all this means that the costumes—and the performers themselves—take a beating. “There’s not a day they don’t need repair,” she says. A performer might slide partway down the pole, controlling the fall with the tension in their arms, legs, or hips. Or, they’ll catch themselves by pinching the pole between their arm and waist before springing off into another pose.

“The acro-poles, in particular, are these two really tall poles right in the middle of the stage,” Livingston says. “They’re covered with a thin rubber, which is great for having to stop and grip. But you can imagine what that may do to your skin. This is one where we do see a lot of burns and skin injuries. And if it’s going to burn the skin, it will burn the costume.”

The costume is made of stretch denim: a pair of straight-leg pants and a jacket with a high collar that ends just below the performer’s chin. Underneath, the performers wear a unitard that’s customized for each individual. Livingston and her team sew in thin layers of neoprene in places where performers need a little extra protection—for some, it’s a patch on their waists, for others, the calves—depending on the stunts they do.

Given the inevitability of tears and burns, it’s hugely helpful to Livingston and her team that these costumes are printed with a scaly pattern, she says. It means that when one area gets worn out or damaged, they can cut around the pattern and replace just that area instead of scrapping an otherwise perfectly good costume. The busy pattern hides the patch far better than a single color ever could.

“I don’t want to replace those costumes all the time for a few reasons: We don’t have an infinite supply, and it’s more sustainable this way. I’m so thankful that the creation team chose this pattern—though I’m not 100 percent sure that this was the top of their priorities when they were designing it,” Livingston says with a laugh. “But what helps is, once you’ve been on a wardrobe team for a while, you take these aspects into account.”

Smart designs

Livingston was hired by Cirque, in 2008, to adapt and maintain acrobatic footwear for the performers in the show KOOZA. She stayed on with KOOZA for five and a half years, then worked on the company’s show Varekai. LUZIA opened in 2016; it’s Cirque du Soleil’s 38th production since the company was founded in 1984, and Livingston joined the production in 2017. The show is touring Australia through January 2025.

At this point, Livingston has held every job in the wardrobe department. The experience has given her a deep understanding of the rigors of the job and the particulars of solving problems on the fly, often as a show goes on just feet away. “You understand what every person on the team needs, and you can back that person up if they need it,” she says.

At BU, Livingston excelled in her costume production studies, says Nancy Leary, an associate professor of costume design and one of Livingston’s mentors.

Since she was hired by Cirque du Soleil in 2008, Livingston has held every job in the wardrobe department. The experience has given her a deep understanding of the rigors of the job. Her speciality is extending the longevity of the costumes, which is especially important for a show that can run 10 years or more.

“She’s just super, super smart in terms of engineering things, understanding how to make things work,” Leary (’03) says. It’s a skill that comes in handy at Cirque, where costumes disappear into the stage floor or change color in real time.

The difference between costume design and costume production can best be understood as a difference between theory and execution. Costume designers are responsible for creating the designs that will help tell the story, transforming words on a page into theoretical visual concepts. It’s the job of the production team to interpret all that and wrangle those designs into tangible pieces worn by performers.

The latter is “like engineering, in a way,” Leary says. “You have to know a lot about the time period, or how to support a costume that might weigh 20 pounds.”

“I love this work”

The costumes that appear onstage at any Cirque du Soleil show are the result of a long design and production process involving hundreds of people. To start, a team of designers dreams up the costumes for the show. In the case of LUZIA, that team was spearheaded by Giovanna Buzzi, an Italian costume designer and daughter of the internationally renowned architect Gae Aulenti.

Buzzi’s background was mainly in opera costumes, Livingston says, so the designer worked closely with a team of artists and craftspeople at the Cirque du Soleil international headquarters in Montreal to advise her on the specific needs of acrobatic performers. Every decision—from the best fabric choice to the most secure (or flexible) stitches and closures—comes from years of experience. There’s no detail too small, either. Even the pit musicians for LUZIA wear costumes. They wear headpieces that look convincingly like crocodile heads bobbing on the water.

From there, the costumes are hand-printed, cut, and sewn in Montreal, then shipped to the show, wherever it may be.

You really have to listen to the performers. They’ll be able to identify a problem in their own costume—they just won’t always know how to fix it, and nor should they.

Livingston comes into the process a year or so after a show has opened, she says. At that point, she can take stock of what’s working and what’s not. Her speciality is extending the longevity of these costumes, which is especially important for a show that can run 10 years or more.

“You’ll notice these problem points pretty quickly, but it’s harder to figure out how to fix them over time,” she says. “You really have to listen to the performers. They’ll be able to identify a problem in their own costume—they just won’t always know how to fix it, and nor should they. They will say something like, ‘I keep getting skin burns here,’ or, ‘My jacket always busts open during this trick.’ And then it’s up to us to use our expertise, diagnose the problem, and find a sustainable solution.”

And so far, it’s working. The pandemic, and its related shutdown of parts of the Cirque headquarters, meant that Livingston and her team couldn’t rely on getting new costumes if older ones wore out; they had to patch and repair, and make them work longer. They apply those lessons today.

The acro-pole costumes, for example, have a high turnover rate. In the past, the LUZIA performers would have worn through three pairs per year. Now, they’re down to two a year.

“There are always going to be repairs,” Livingston says. “You can’t make a perfect costume, especially with performers like ours, who are constantly pushing the envelope and trying new stunts. But my brain loves fixing problems, and there’s no shortage of those. I just love making things work better, and more sustainably. It’s a lot of work, but I love this work.”