Saving the Classical Music Ecosystem

How music criticism and classical music adapt with the times to remain relevant

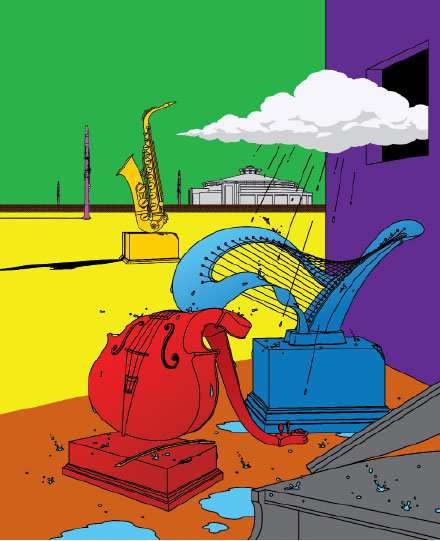

By Lara Ehrlich, Illustrations by Edward Carvalho-Monaghan

Saving the Classical Music Ecosystem

How music criticism and classical music adapt with the times to remain relevant

On November 14, 1943, Leonard Bernstein, then just 25, stepped in at the last minute to cover for the New York Philharmonic’s ailing conductor at Carnegie Hall. The concert was broadcast live on radio to millions of listeners, and was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. “Mr. Bernstein [Hon.’83] advanced to the podium with the unfeigned eagerness and communicative emotion of his years,” the Times critic wrote. Bernstein’s philharmonic debut was news, and the review catapulted him to fame.

In Bernstein’s day, classical music received almost as much coverage as professional sports. That was true into the late ’70s and ’80s, says Tony Beadle (’74), executive director of Rockport Music, who was performing double bass with the Boston Symphony at the time. “When you opened the Boston Globe on a Monday morning, three critics covered a lot of music in long articles, and their reactions were important to musicians,” he says.

Now, readers would be hard-pressed to find those stories in the popular press. Papers are trimming costs to compensate for plummeting profits, a trend that began in the ’80s. The arts section took the greatest hit, with classical music criticism as the first casualty.

The decline of classical music’s visibility in the mainstream media is a blow to an art that’s struggling to draw audiences. Attendance, already lagging behind that of other performing arts, has been declining for decades. The National Endowment for the Arts reports 11.6 percent of adults in the United States attended a classical music performance in 2002. By 2017, that number had dropped to 8.6 percent.

CFA spoke to three experts—Beadle, Anthony Tommasini (’82), the chief classical music critic for the New York Times, and Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94), an opera producer known for mounting innovative new work—about how classical music criticism is changing, how those changes are transforming classical music, and the role, and responsibility, of the contemporary critic.

SLIPPING OUT OF THE MAINSTREAM

In the three years following the Great Recession of 2008, half of the arts journalism jobs in the US disappeared. And they’re not coming back. As newspapers have slimmed and folded, specialized art critics—those who cover genres like dance, theater, and classical music—have become arts generalists, been laid off, or moved to different beats. (In 2016, the San Jose Mercury News scrapped its classical music coverage and consigned its critic to covering real estate.) Only a very few specialists remain, and of those, “I can count the number of full-time classical music critics on both hands,” Douglas McLennan, the editor of ArtsJournal, told San Francisco Classical Voice.

Tommasini is one of these rarities. A trained pianist, he performed and taught music until switching to journalism; he’s been the chief classical music critic at the New York Times since 2000 and has written four books on music. With so few experts in classical music criticism, Tommasini and his handful of peers have become the voices of authority on the genre.

But they can’t possibly cover every concert or every new piece of music—and the choice of what to cover is constrained by the need to attract readers in an industry obsessed with clickbait.

“Reviews of concerts are minimal,” says Beadle. “Critics just don’t have the space and the time to write about a concert’s complexities, as they might have at one time.”

I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.

“This has done a terrible disservice to the classical music industry,” says Morrison, one of the most sought-after producers in the opera world and founder of the indie opera company Beth Morrison Projects. Morrison collaborates with composers to develop new works: she assembles the creative team; works with the artists to identify and implement the creative vision for the piece; secures the world premiere venue, funding, marketing, and publicity; and develops the pitch materials. Critical coverage of her projects is vital to their success and longevity, she says. “I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.”

It’s not just the word count that’s crippling classical music, says Beadle, who considers the biggest loss to be “articles about music in the mainstream; that’s what criticism was. Those reviewers brought not only last night’s concert to readers, but also the world of the musician and what they’re doing artistically.”

Amid the cutbacks, amateur critics have stepped in, putting more of an onus on readers to vet their sources. “You can find bloggers and critics writing on internet sites who are astute, informed, lively, and fair-minded, and you can find opinionated, untrustworthy know-it-alls,” Tommasini says. “Established journals and newspapers vouch for their critics and reporters and hold them to high standards. The internet challenges users in all fields to make their own determinations about the reliability of the voices they read.”

Beadle points to one internet source he finds reliable, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, billed as “a virtual journal and essential blog of the classical music scene in greater Boston” that features contributions from 80 musicians, composers, academics, and music aficionados.

“It’s harkening to the old days because writers have plenty of space” to take on the complexities of classical music, Beadle says. This kind of journalism is “a 21st-century answer to what has happened in classical music criticism.”

In this new wave of nonprofessional critics, Tommasini believes his voice is not only still relevant, but that “it matters more and more. When there’s so much chatter and so much writing out there about the arts, a trustworthy voice at a place like the Times cuts through.”

He does his part to keep pace with a changing industry by incorporating multimedia to keep his readers engaged. In a 2017 review of Trinity Wall Street’s concert in honor of composer Lou Harrison, Tommasini included Spotify links to musical elements he wanted readers to appreciate; for instance, how “the slow second movement, a Siciliana in the form of a double canon, unfolds in skillfully written counterpoint. Yet the lines creep up and down and overlap with impish freedom.” Or, how “the aptly named Stampede movement races along like some combination of Asian dance and American hoedown.” Thanks to the web, readers can listen to 30-second snippets and hear for themselves what the critic is enthusing about.

Tommasini also embeds YouTube footage of concerts in his reviews, and films his own educational videos. He’s not alone in using the internet to his advantage; his fellow critics are also changing with the times to keep—and build—their readerships. Alex Ross, longtime music critic for the New Yorker, supplements his print criticism with his popular blog, The Rest Is Noise, in which he posts photos, videos, and music clips with brief commentary.

Tommasini doesn’t see the internet as a competitor, but as a complement to his work. The print and digital versions of the New York Times “go together,” he says. “You can read something on one or the other and have a rich experience, but ideally you look at both. That’s opened up all sorts of possibilities while also introducing challenges. It’s changed the way we do arts criticism.”

Tommasinistillemploys old-school techniques, like evocative writing, to engage readers as diverse asscholars, conductors, musicians—and people who’ve never seen a classical musical performance. He writes about music in a way that the general reader can understand, a tricky enterprise that some other beat writers don’t face. “The typical crowd at Yankee Stadium knows more insider information about baseball than the typical audience at the New York Philharmonic,” he says. “I envy sports writers tremendously for all the knowledge that they can assume their readers have.”

Plus, as he points out, “it’s very hard to describe sound in words. We have this handy technical language to do that, but only musicians know it. I can’t just use a term like chromatic harmony without losing readers.” His talent for describing music in vivid and accessible language is part of what has earned him a reputation for being “entertaining, highly enthusiastic, and very knowledgeable,” says Kirkus Reviews, “he’s the perfect guide.”

About a performance of Sibelius’ Fourth Symphony, Tommasini wrote that the second movement “sounds like a fractured dance in which the broken parts have been reassembled, but in the wrong way.” About a Leonard Bernstein performance of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring”: the opening solo melody “slowly instigated a restless tangle of squirrelly lines that became a needling, nasal-toned free-for-all.” The goal is not just to engage readers, but to turn them into listeners.

“It’s complicated, because on the one hand, I’m here to inform people about music—but I also want people, especially young newcomers, to take a chance on a concert,” he says. “An opera or chamber music program is not an exam; you don’t have to take a music appreciation course first. Just go.”

THE FRAGILE ECOSYSTEM FACES COLLAPSE

Despite the fact that their numbers are declining and their roles diminishing, critics still have an outsized impact, particularly when it comes to new works. “Most artists I know feel that the critics have an enormous amount of power; essentially, the power to make or break careers,” Morrison says. “At the same time, critics don’t have jobs without the artists they are hired to write about. With this interdependence comes responsibility. A media member should always be rooting for an artist’s success; without that, the ecosystem, which is already incredibly fragile, faces imminent collapse.”

Reviewing new work is “when a music critic can really matter, if a first performance is going to lead to a second, a third and a future for the piece,” Tommasini wrote in the New York Times. He takes that responsibility seriously, and he approaches new work with an open mind, suggesting that critics do a disservice to new music by coming to it with predetermined criteria for greatness.

His latest book, The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide (Penguin Press, 2018), is in part a meditation on greatness. “All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so,” he says. “We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming, so greatness can get in the way. We hold up the giants and compare new composers to them.”

All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so. We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming.

“Imagine if you were teaching a short story workshop and young Franz Kafka showed up, with those very peculiar stories,” he wrote in the New York Times. “Would you chide him for some assault on language, or perhaps consider that he might be on to something strange and new and fascinating? If I err on the side of being open-minded in reviewing a new work, that’s O.K. by me.”

Organizations can help keep their industry alive by embracing new work, he says. That’s not such an easy task, as many classical music institutions are struggling to fill seats, especially in the absence of reviews that once sparked public excitement and spurred ticket sales, Beadle says. “They have to rethink their strategies.”

Musicians and orchestras are doing just that, by performing in nontraditional venues (the San Francisco Symphony hosts SoundBox, a concert series in a warehouse), experimenting with technology (the Boston Symphony Orchestra is loaning patrons iPads programmed with information about the performances), and adjusting ticket prices (the Cleveland Orchestra allows students to attend as many concerts as they’d like for $50 a season).

And many schools, like the School of Music at CFA, encourage musicians to seek creative ways to pursue their passion. For instance, CFA hosts an annual career development workshop series, which includes presentations on issues like freelancing, taxes for artists, financial literacy, and developing an online presence. Courses like Cultural Entrepreneurship and the Creative Economy and Social Impact promote entrepreneurship, and a minor in arts leadership gives students the opportunity to further develop their expertise.

Beadle believes classical music still holds plenty of promise. At music schools like Boston University Tanglewood Institute, he says, “you will see hundreds of kids playing classical instruments. And all the music schools are filled with students who want to play their instrument and excel at it.”

Those artists give critics something to write about—and ensure the relevance of music criticism. “Not only do artists contribute to the cultural and social richness of their community,” Tommasini wrote in the Times, “they make news. . . . A review is both an opinion column and a news report.

“But the most astute and simple defense of the role of the critic I know of came from (no surprise here) Virgil Thomson, [a composer-critic who] wrote that while traveling in Spain he was fascinated to see that it always took at least three children to play at bullfighting. One to be the bull, another to be the toreador, and a third to watch and shout ‘Olé!’ Music criticism is like that.”