Painting With Purpose

With a team of local street artists, Josué Rojas (’15) painted the mural Birds of the Americas in San Francisco’s Mission District. Photo by Gabriela Hasbun • Photo by Gabriela Hasbun

Painting With Purpose

Blending classic techniques with street art, Josué Rojas represents his Latinx community with a unique voice

Hundreds of murals illustrate the streets and alleys of San Francisco’s Mission District where Josué Rojas works. They tell the stories of immigrants to the historically Latinx neighborhood. They honor women and LGBTQIA+ pioneers. And they give a voice to a community pushing back against police violence and gentrification. Graffiti and street art merge in this open-air gallery.

Rojas (’15) has lived or worked in the Mission since he was a toddler—his family settled here after fleeing El Salvador’s civil war—only leaving to spend two years at CFA. Since first picking up a paintbrush as a teenager, Rojas has developed into one of the community’s leading artistic voices, frequently exhibiting his work, painting murals, and encouraging other artists to tell their own stories.

“In this community, art is the glue,” he says. The neighborhood that led him to art and continues to inspire him today has also given him the confidence to take a big leap: in 2021, he decided to strip away his other obligations—including running a local nonprofit—and focus full time on his art.

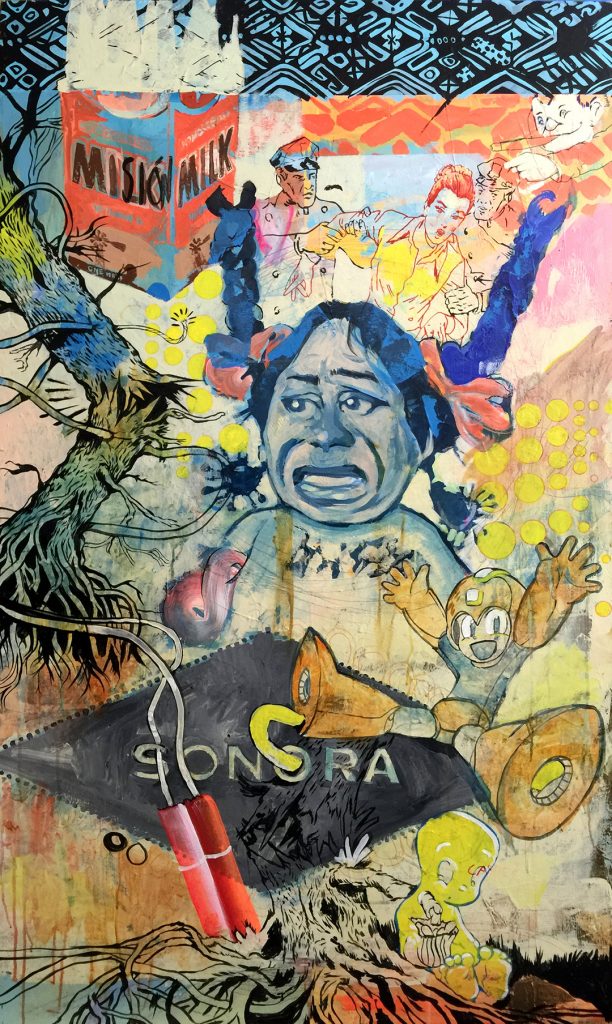

La Palabra y La Imagen (2016) Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 40 in. In this piece, Rojas draws from the Mayan creation story, the Popol Vuh, which features twin brothers—one is a poet and one is a painter—to highlight the connection between words and images. Courtesy of Rojas

Mastering the Language

Rojas says his life could’ve gone in a very different direction. His father died when he was 15, and he began acting out. “I started getting in trouble, writing graffiti.” But he also got a part-time job at Precita Eyes Muralists, a nonprofit that has promoted art in the Mission since the 1970s. Soon, he was learning to paint.

“It was the first time I had found something that I was actually good at,” he says. Small jobs followed: designing murals, illustrating stories for the Pacific News Service, a publisher of independent journalism. Rojas began writing for them as well, continuing to report while he studied painting as an undergrad at the California College of the Arts.

Reporting trips to Central America inspired his art and gave him the financial flexibility to pursue it. But when journalists began getting killed by gangs, Rojas reevaluated his plans. He learned about BU while attending the Institute for Recruitment of Teachers at Phillips Andover Academy in Andover, Mass., which promotes diversity in teaching and educational leadership. He liked the idea of stepping away from home to see what he could accomplish when focused entirely on his art.

Rojas speaks of art as a language and says his decision to study at CFA helped him expand his vocabulary. “I felt very comfortable with urban art and what’s understood as Mexican heritage—classic murals inspired by Diego Rivera and then evolving into the Chicano movement of the 1960s,” he says. Two years in Boston allowed him to develop classic techniques and styles, like abstract expressionism. “Now I feel very comfortable being bilingual—I can speak East Coast and West Coast within American art.”

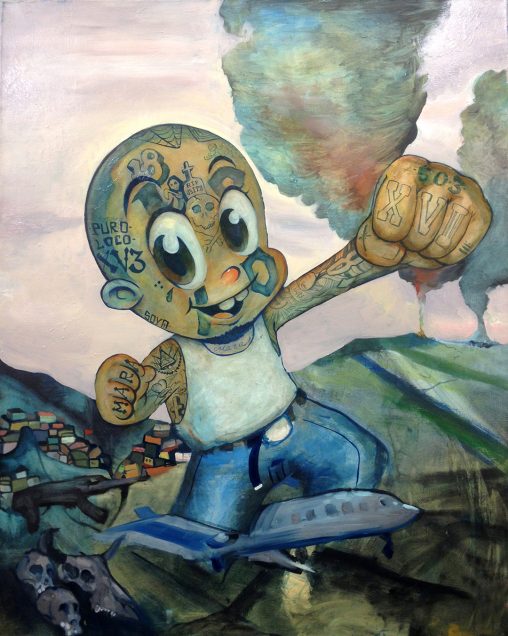

His thesis collection, The Joy of Exile, featured a series of paintings, but Rojas’ vision extended well beyond the canvas. He continued the images onto the walls and mixed in stanzas from a friend’s poem. In what is a Rojas trademark, cartoonish characters clashed with organic forms and familiar logos. The Boston Globe wrote that the installation “has the quality of a fever dream: roiling color and gesture. Violent imagery leavened with pop culture references.”

Rojas returned to San Francisco as soon as he completed his MFA in painting. As one of his class’ Kahn Award recipients, he received a grant that helped him set up a studio in the Mission and fund his next exhibit, ¡Gentromancer! He also accepted a position as executive director of Acción Latina, an organization that promotes arts, community journalism, and civic engagement in Latinx communities in the Bay Area.

For ¡Gentromancer!, which opened in 2016, he focused on the threat of gentrification to the Mission—and played with the styles used for his thesis. The 1980s cartoon robot Voltron frames one painting, La Palabra y La Imagen (“The word and the image”), looming over a canvas dense with images: a steaming volcano, a snapping tree trunk, blowing winds, two faces in silhouette. Voltron, which was formed by five smaller robots, symbolizes unity and a community’s ability to be stronger than the sum of its parts, Rojas says. The overall effect is of a Mayan mural morphing into a comic book panel.

In another painting, Amor: the Perfect Lotus, the face of Alex Nieto, who was killed in 2014 by San Francisco police in a nearby neighborhood, is divided into quarters, each rendered in a different style, a charcoal sketch abutting a splash of Warholian color, above a cartoonish minimalism. Rojas also coordinated a special broadside—published by El Tecolote, a bilingual newspaper now produced by Acción Latina, where the exhibit took place—which included poems from 17 local writers. For Rojas, art and community are intertwined.

Expanding the Outdoor Gallery

Although the Latinx community has been particularly hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, Rojas decided to coordinate a large team project in fall 2020. Birds of the Americas, an 80-foot-wide and 25-foot-tall mural in the heart of the Mission, celebrates the lives of four men, each depicted as a Central American bird: El Salvador’s torogoz for Andres Guardado, a toucan for Sean “Tucan” Monterrosa, and Guatemala’s quetzal for Amilcar Perez-Lopez and Luis Gongora Pat. Guardado and Monterrosa were both shot by police in June 2020 while Perez-Lopez and Gongora Pat were killed by police in 2015 and 2016, respectively, within blocks of the new mural.

Rojas’ mural Enrique’s Journey (2009) was inspired by Sonia Nazario’s book of the same name and is located at Balmy Alley in San Francisco. Photo by Gabriela Hasbun

Rojas focused on painting the birds and assembled a team of local street artists and graffiti writers to complete the mural, assigning each a 20-foot section. The artists worked in shifts, to remain socially distanced, and over three weekends they gradually covered the massive wall with tropical yellows, greens, reds, and pinks. Vines, flowers, slices of guava, graffiti letters, and a mythical deity are entwined in the finished piece.

“Murals are an external expression of a community’s internal values,” Rojas told Mission Local, a neighborhood news organization. “For our community to see that a mural is going up, even during these conditions, during the fires and pandemic. For them to see we are coming together, making something beautiful during this time, [that is important].”

Though he’d designed the birds in advance, Rojas didn’t know what the other artists would do with their space. “There’s a lot of trust,” he says, comparing the project to a jazz album. “Miles Davis wasn’t simply a great trumpeter. He laid the groundwork for a group of people to shine, and they made the Kind of Blue album.”

More to Say

The challenges of the pandemic, including illnesses in his family, helped Rojas realize where he wants to focus his energy. After four years as executive director, he stepped down from his role at Accíon Latina. For the first time since CFA, he’s focused entirely on his art.

“It can be very daunting to stare at an empty calendar or stare at my bank account,” he says. But he’s taking comfort in the words of one of his professors at BU: “Take care of the art and the art will take care of you.”

And he couldn’t be in a better place to do so. Even as the Mission changes and longtime residents are priced out, Rojas sees positive signs. There are still more walls to paint and new galleries keep opening, allowing voices like his to continue to be heard. “It’s a revolutionary act,” he says, of his community’s insistence that art is important.

Occasionally Rojas hears an old adage: “Painting is dead.” He bristles at the suggestion. “It really is disrespectful, not only to the practice of painting, but also the people who are now able to speak. I really believe there’s a lot more to be said.”