The Accidental Filmmaker

Cécile Fontaine deconstructs and manipulates found footage, bringing collage to life

Photos by Augusta Sagnelli. Film images courtesy of Fontaine and Light Cone

The Accidental Filmmaker

Cécile Fontaine deconstructs and manipulates found footage, bringing collage to life

Cécile Fontaine has made more than 50 films over four decades, but she rejects the label of filmmaker. “It’s just collage; it’s not real filmmaking,” she says. “It’s working on film.” Fontaine (’83) says this on Zoom from the Paris apartment where she has lived and made art for 30 years. It’s one of many self-deprecating comments that she makes.

A reel of film and a light box sit on a table behind her. The other tools she uses are within reach. Fontaine occasionally grabs one of them and holds it up to the camera. They’re all household products, like liquid cleaners and Scotch tape. She uses scissors, knives, and a splicer. Boxes of found film—strips and spools of footage given to her over the years, rescued from the trash, or purchased at flea markets—provide her raw material.

Cécile Fontaine manipulates found film footage to create new works of art. She deconstructs developed images with liquid baths or metal implements. Then she builds a new film from the pieces.

She cites collage artists Jacques Villeglé and Mimmo Rotella as influences rather than French cinema luminaries like François Truffaut or Jean-Luc Godard. But her finished products are films, intended for projection. They just happen to defy every moviemaking tradition and norm imaginable. She seems as amazed by her success as she is by the unpredictable outcomes of her artistic experiments.

Rather than make an image in camera, Fontaine deconstructs developed images with liquid baths or metal implements. Then she builds a new film from the pieces. Her works lack a narrative arc and rarely include sound. They might best be described as moving collage. The effect can be like riding a merry-go-round with a kaleidoscope pressed to one eye.

Artist yann beauvais, cofounder of the experimental film nonprofit Light Cone, has written about the first time he saw one of Fontaine’s films: “There was something deeply moving in the discovery of a new use of the film, or more precisely in the way of making cinema.”

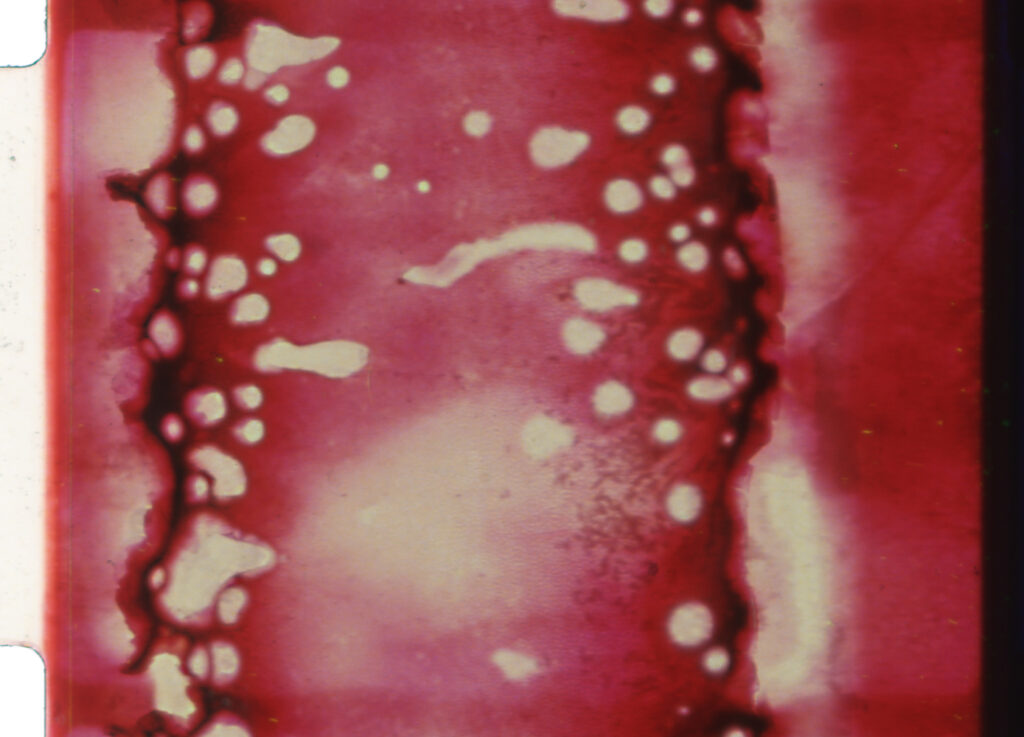

Images from the film strip for The Last Lost Shot (1999), which Fontaine made in response to the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado.

The Practical Artist

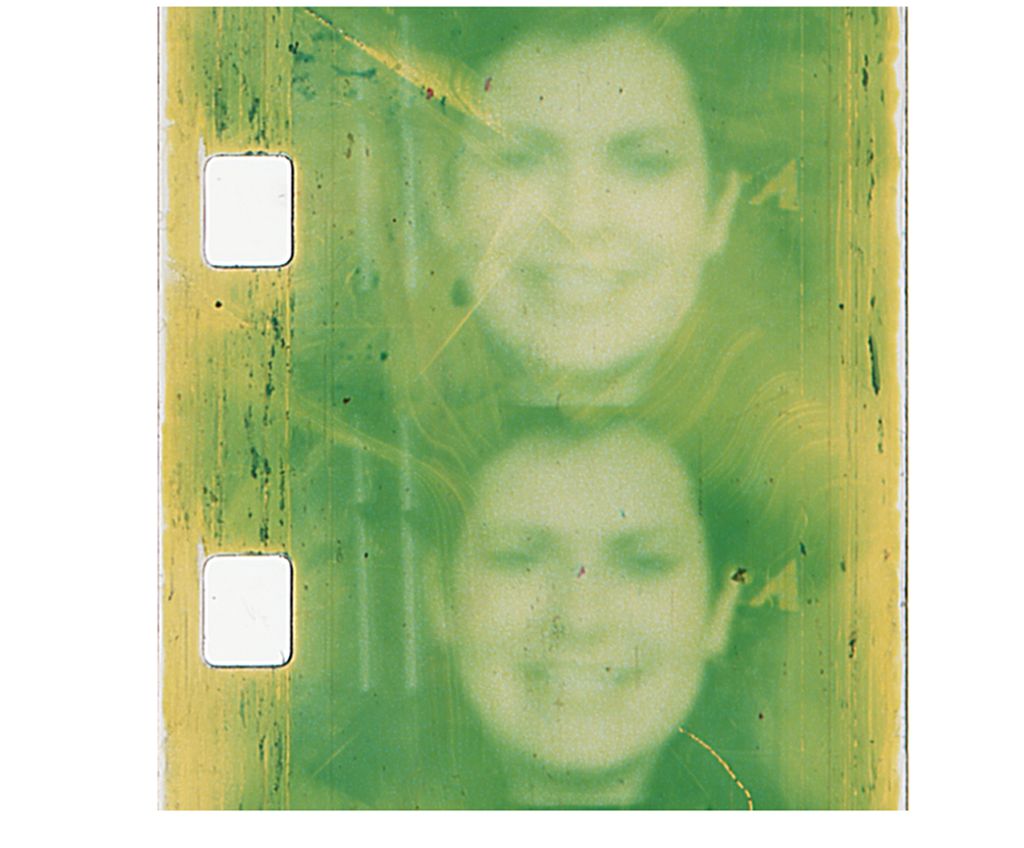

Fontaine studied art education at CFA, but she also wanted to create her own art. She carried a Super 8 camera around Boston and began experimenting with her footage. One of her first films, Irène (1982), shows a friend riding a unicycle in her apartment. Fontaine soaked the film in bleach, which removed a layer of emulsion and gave the images a green tint. Manipulating emulsion (film’s light-sensitive chemical coating)—just as a sculptor might work with clay—has been a hallmark of her work ever since.

Fontaine enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University after BU. Her formative creative decisions were exceedingly practical. Film, she figured, would be easier to transport back to Paris than bulky paintings. And to manipulate her films, she used cheap household products like Fantastik and Clorox bleach. “I thought that if I could use it to clean my clothes, it was OK for film and for my health.”

From there, Fontaine’s style began to take shape. “It was always through a mistake,” she says. One day, she peeled a piece of tape off a section of film and noticed that some emulsion came with it. That became her dry technique.

Irène (1982), one of Fontaine’s first films, in which a friend rides a unicycle in her apartment.

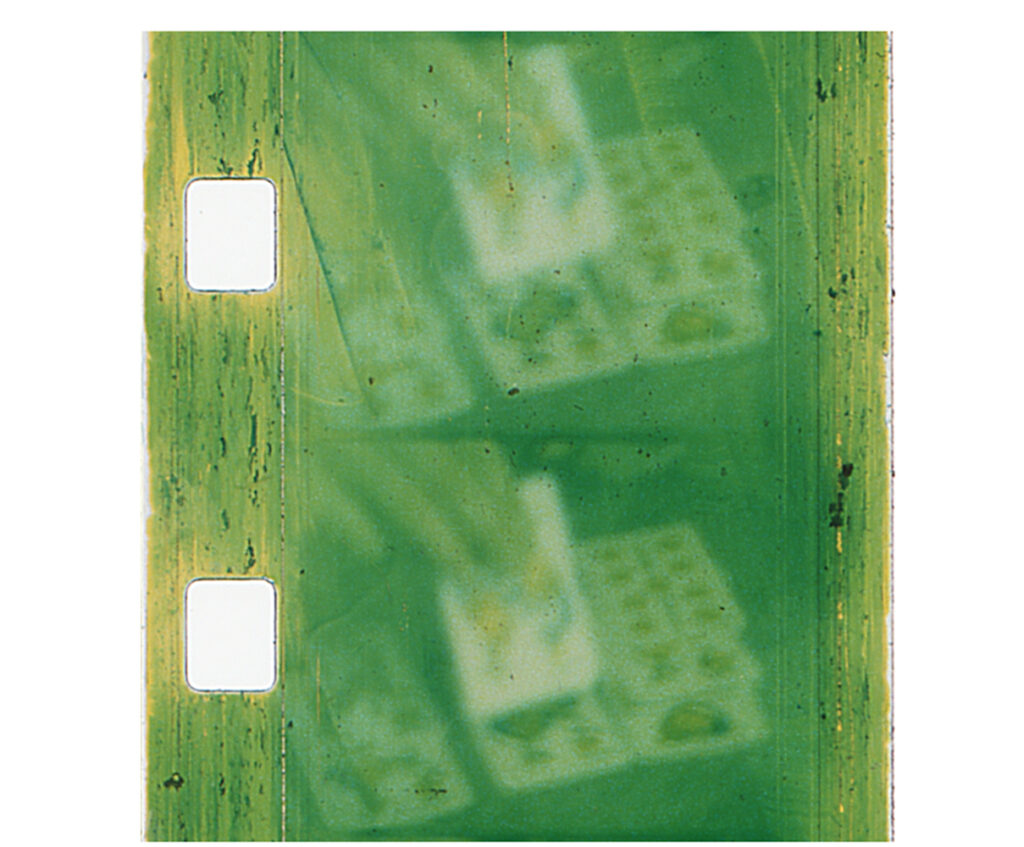

For Golf-Entretien (1984), Fontaine soaked a film strip in Fantastik. To her surprise, the emulsion expanded. She removed the excess with a painter’s palette knife and reapplied it elsewhere on the film strip. The result was a dual image. An instructional golf video plays in the background while the distorted images from the reapplied emulsion, punctuated with swaths of green and magenta, flash by. This became her wet technique.

Fontaine recalls her classmates “looking at me with big eyes. They didn’t understand what I was doing.” While many of her peers focused on animation—the act of creating images to transfer to film—Fontaine was, in essence, doing the opposite by removing images from filmstrips.

“I did everything you weren’t supposed to do. I just explored the material,” she says. She experimented with scratching and puncturing film with steel wool, scissors, and razors. She soaked it in ammonia, bleach, soapy water, and vinegar. She wrote on the film and pasted acetate to it, then ditched those methods when she saw other filmmakers using them.

“I wasn’t good at techniques, and I just disliked techniques,” she says. Rather than learn them, she created her own.

Fontaine soaked film for a golf video in Fantastik and manipulated it to create a dual image for Golf-Entretien (1984).

Expecting the Unexpected

Fontaine moved to Paris in 1986 and contacted Light Cone for the first time. That’s when beauvais watched her early work, launching a decades-long relationship. Their ability to promote her art helped Fontaine reach a broader audience while balancing new projects and a full-time job as a teacher.

To start a project, Fontaine looks through her film collection. She holds strips up to the light to examine the images—never projecting them until she’s done manipulating them—and searches for colors, textures, and movement that please her.

Fontaine typically isn’t concerned with the subject matter of the images, though she has created films in response to the AIDS epidemic and the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado. In The Last Lost Shot (1999), she juxtaposed children’s illustrations with a Winchester rifle commercial—a mash-up of youthful innocence and gun culture. She soaked the film in water and powdered laundry detergent, which created a red tint. The damaged layer of film moves like an organic animated blob threatening to consume the rifle-wielding men.

“It was always through a mistake,” she says. One day, she peeled a piece of tape off a section of film and noticed that some emulsion came with it. That became her dry technique.

Despite the basic methods Fontaine uses, she never knows what a film will look like when it’s done. “I’m always surprised,” she says. “Sometimes I don’t understand what has happened, and it’s difficult to do the same thing [again].”

When she soaked film in soapy water for Parallel Stories (1990), sections of emulsion unexpectedly burst. Water bubbles worked their way between the remaining emulsion and the film and left residue behind. The image looks as though it’s been eaten away by a splash of acid.

Using black-and-white footage of plankton, discarded by a natural history museum, Fontaine created Spaced Oddities (2004) by editing each individual cell of 16 mm film—approximately 1,500 frames. She executed her dry technique by laying double-sided tape on her desk and pressing the film onto it, then peeling it off. She trimmed the perforations with scissors, then taped each cell at a 90-degree angle onto another strip of film. What would have been organic movements of the plankton turn frenetic with her editing.

“Fontaine constructs an imaginary world, a phantasmagoria of colors and shapes that transports the spectator to a parallel visual universe,” Lucia Tralli wrote in a 2016 essay for the journal Feminist Media Histories. “Hers is a cinema that rigorously refuses the movie camera.”

Spaced Oddities (2004) used footage of plankton discarded by a natural history museum.

In 2009, Fontaine went digital, experimenting with video. She would manipulate film then scan it for additional editing on her computer. She also began filming some of her own footage again. The computer allowed her to make dramatic edits with the click of a button—generating kaleidoscopic sequences impossible to create with scissors and tape. “But I don’t really like my work in video,” she says. “I missed the materiality of the film, transforming it by direct action on its surface.”

Fontaine retired from teaching in 2021. The same year, a retrospective exhibit in Paris celebrated her career and was accompanied by a book she’d created in collaboration with yann beauvais, L’émulsion fantastique (Light Cone, 2021). The name pays homage to her use of Fantastik.

Fontaine is modest about her success. “Some people say that I’ve influenced them,” she says. “That’s always a surprise. I never think about the people who are going to see the film.”

Watch some of Fontaine’s films here.