Art Reimagined

Alums Christopher Morrison and Julie Gratz are using technology to push artistic boundaries

Illustration by Ryan Snook. Photos by Alun Callender (Morrison) and Jeff Wilson (Gratz)

Art Reimagined

Alums Christopher Morrison and Julie Gratz are using technology to push artistic boundaries

You find yourself in a California mining town in 1851. A full moon shines brightly. Suddenly, your limbs are extending, fur starts growing all over your body, and sharp claws emerge from your fingers and toes. You let out a guttural howl.

You are in The Werewolf Experience, a short, interactive virtual reality (VR) game created by Christopher Morrison, a writer and director based in London and Brussels. Through his company Reality+, Morrison (’96) has developed and produced his own plays, shorts, and feature films. He’s also contributed storylines, dialogue, and character development for video games, including 2024’s Outcast: A New Beginning.

“I’m a narrative guy,” he says. “I’m drawn to character-based stuff that’s a little bit weird.” In 2016, he was inspired by his wife, who at the time was the head of emerging technologies for Procter & Gamble and working on VR projects for the company, to try a new format and begin an offbeat VR project of his own. “I started to consider VR as an artistic enterprise,” he says, “and the very first thing I thought of was: everybody wants to be a werewolf.” In his game, you’re being chased by townspeople in the failed Gold Rush town Fool’s Errand, Calif. “You’ve heard a rumor that there is a white stag in the forest outside the town and that it can cure all disease,” explains Morrison. “So, your goal is to hunt the stag to cure yourself of lycanthropy.”

Morrison created the short, interactive VR game The Werewolf Experience. In the game, you’re a werewolf being chased by townspeople in the failed Gold Rush town Fool’s Errand, Calif. Courtesy of Morrison

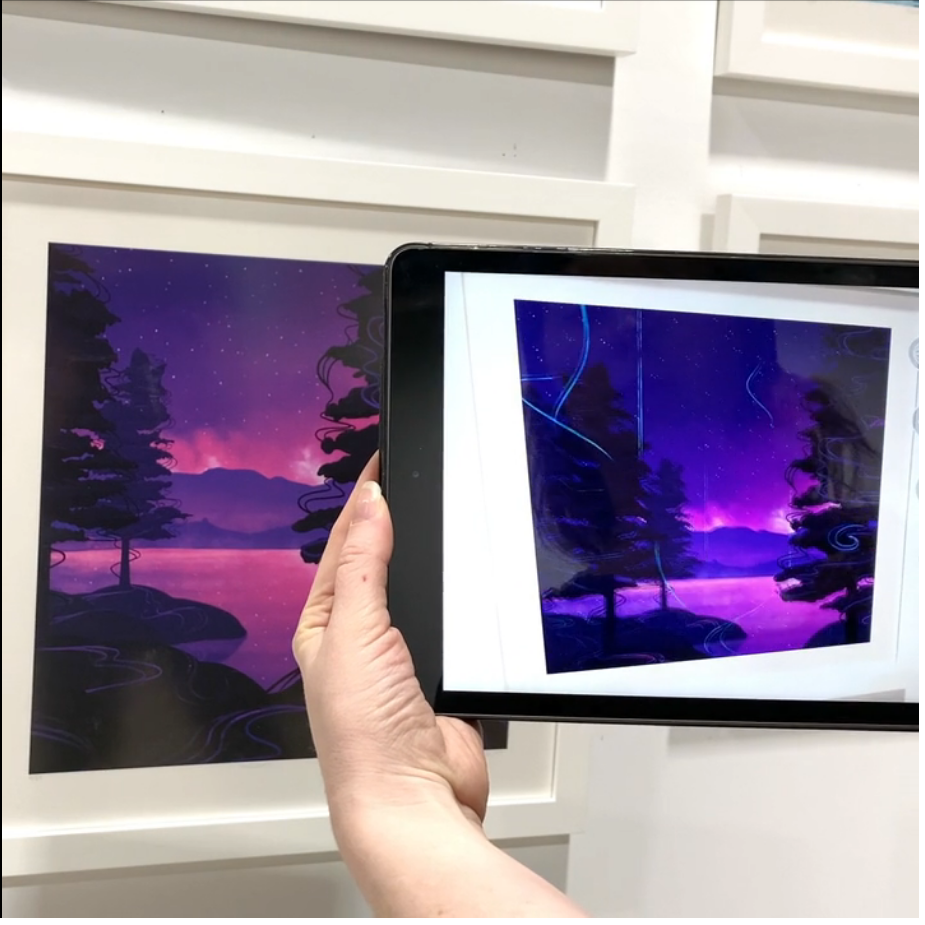

Morrison is just one alum turning to tech to enhance an artistic vision. Julie Gratz, an artist and animator based in Austin, Tex., helped develop an augmented reality (AR) app that makes static prints come to life. When a viewer holds up a phone or tablet to a print on the wall, the app shows an animated version that has depth, movement, and sound.

In a piece Gratz created, Above/Below (2018), a print of trees above a rocky stream in daylight gets turned on its head in a trippy animation when activated with the app. The image rotates 180 degrees, and in the process the scene turns from daytime to night.

Gratz (’11) runs the video and animation production company Kaleida Studio. In addition to creating her own AR work, she represents other AR artists, but her primary focus with Kaleida is creating nonfiction animation for documentary films and series. She keeps her finger on the pulse of the latest tech: she’s begun exploring how to use artificial intelligence as a tool in her work.

Morrison and Gratz started out on more traditional paths at CFA, but both have always harbored a spirit of innovation. Morrison was an acting student but later chose to pursue an independent theater studies track to explore all of his interests. Coming from a martial arts background, he was especially interested in physical work and stage combat. “I was able to cobble together this weird sort of movement for the stage BFA program,” he says. “I was able to pursue all the movement, acting, directing, and fight stuff that I wanted to. It definitely set me on a path of learning everything.”

Gratz was a graphic design major but was drawn to animation through a multimedia class she took. “We did one or two little animation projects in Adobe Flash,” she recalls. “My brain clicked a lot better with designing with motion and time than it did with static graphic design pieces. I think where that comes from is, I have a whole background with dance and performances and musicals. So, to me, animation was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m choreographing my artwork. It can be to music. It can have rhythm.’ I was immediately like, ‘Oh, wow, this is what I need to do.’”

I started to consider VR as an artistic enterprise, and the very first thing I thought of was: everybody wants to be a werewolf.

In the spirit of their boundary-pushing ethos, both have embraced new formats and technologies to express their creativity throughout their careers. They are now doing so at a time of rapid advancements and when more questions around ethical issues of technology, especially AI, are arising. Some question whether purely AI-generated imagery is art, and many artists are concerned that generative AI art programs could be drawing from copyrighted content.

Morrison and Gratz are aware of these issues but are also intrigued by the constant developments in the technology.

“I just consider myself as someone with some experience in the [VR] industry as it sits right now,” says Morrison. “These days, everything’s in flux. The tech seems to change almost weekly. And that’s also one of the reasons it’s very exciting.”

Why VR?

If it seems unusual that more artists are integrating technologies like virtual reality into their work, consider the words of Jaron Lanier, a pioneer in the field. “VR can be a way of exploring the nature of consciousness, relationships, bodies, and perception. In other words, it can be art. VR is most fun when approached that way,” Lanier writes in the New Yorker article “Where Will Virtual Reality Take Us?” He later adds, “I’ve always thought that VR sessions make the most sense either when they accomplish something specific and practical that doesn’t take very long, or when they are as weird as possible.”

Morrison seems to have taken Lanier’s view to heart. All of his creative pursuits—including his foray into VR—stem from his love of role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, which he enjoyed for allowing him to develop characters and explore their relationships to each other. “Sitting around a table, improvising a story with a group of people, is still at the core of what I do,” Morrison says.

I have business cards that are AR, if you activate them. The animation side still blows everyone’s minds and gives people a lot of joy.

As for Lanier’s point about doing something specific and practical, and embracing the weird? Morrison did just that in The Werewolf Experience, which he worked on mostly over the course of COVID lockdowns. He came up with the script for the story and then partnered with The Pack Studio, a Belgium-based visual effects company, to produce the animated VR short. Since its completion in 2022, The Werewolf Experience has been in festivals around the world—it was one of three VR pieces to be featured at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival—and Morrison is also working to release it for download on the gaming platform Steam.

With The Werewolf Experience, Morrison was trying to address something he’d long thought about when it came to traditional video games. “One of the things that always bothered me was that we would have the same controller for every game,” he says. “I know a lot of people would say, of course, it’s the only way to do it. But I’ve thought about what if there were a different controller for every game we made. It would give you a different interaction. I think the controller becomes a trap; narratively and mechanic-wise, you’re stuck in this ‘box.’ With VR, it’s worse because the controllers are even more simplified.”

Then Morrison started thinking: What if he eliminated the need for controllers entirely? “You have a new body and you’re in a new world, but if you’re needing to use the thumbsticks on controllers you’re holding, you’re in two places at once. So, the mechanic that I wanted to deal with was that you control everything with your voice.”

And since you are a werewolf, that means you howl. At key moments throughout the story, whether you choose to howl or stay silent affects what happens next. There are three different endings depending on the decisions you make throughout the game.

While variations of VR have been around for many decades, the technology has quickly advanced in recent years. It started to become mainstream in the mid-2010s, when companies like Meta, HTC, and Sony began selling headsets with high-quality graphics to use at home, mainly for gaming. In February 2024, Apple got into the VR mix with its Apple Vision Pro headset. Today, VR is being used in a multitude of ways in many fields, including education, retail, and healthcare.

The technology may be more widely accessible, Morrison says, but people are still figuring out its best applications. It requires careful thought about what content is best served by the technology. “If you’re doing a VR thing,” he says, “it has to have some kind of mechanic at its core that takes advantage of virtual reality. Otherwise, why do it in VR? People just throw stories at it that don’t make any sense for the technology.”

While companies like Apple and Meta continue to invest in VR, all is not well in the industry. CNBC reported last December that sales of VR headsets in 2023 decreased by nearly 40 percent.

Morrison acknowledges the volatility of the industry, but he is hopeful about its future. “VR has been declared dead maybe six different times ever since it was introduced in the ’90s—really, in the 1960s if you want to get specific, but I’m talking since the ’90s, when the potential really arrived,” he says. “Most people consider 2016 as year zero [of VR as it is today], when the first generation of the Oculus Rift dropped. Even from then, it’s been declared dead twice. We’re in a weird valley right now, but I personally think it will come back, and I’m excited.”

Animation of the future

Like Morrison, Gratz is attuned to the constant flux of technology. Back in 2018, she was living in Brooklyn and sharing a studio building with a tech production company. They encouraged her to try working with AR.

“At the time, I was like, ‘I don’t understand AR, that sounds crazy,’” she says. “But I realized that, with AR, the hardest part is what happens when it is activated—the animation itself. And I already had experience with that.”

She made some new animations and created prints from them—“It’s basically printing out one frame of the animation,” she says—then connected the prints to an AR app called Artivive. She hosted an open studio event to show off the interactive work and was thrilled with the reaction: “It blew everyone’s minds. It was really satisfying and fun.”

Left: Julie Gratz’s Forest Cathedral (2019). Right: Above/Below (2018). The prints can be activated with the Artivive app. Courtesy of Gratz

From there, Gratz showed other animator friends how to make AR prints and began representing them. She had group shows around the country. For an Art Basel Miami exhibit in 2019, she partnered with two friends to create their own Kaleida Studio AR app. They incorporated a feature that makes a paired image appear three-dimensional inside its frame; when a viewer moves their device around, the image’s depth changes.

Gratz had plans for many more shows, but those tapered off during the pandemic. She’s still selling the AR prints and hopes to resume creating more AR art soon. “I have been making some animations that I haven’t released in a while,” she says. “My goal is to continue the AR artwork with things that are not only these gallery-quality prints that people can buy, but also much more affordable options. For example, I have business cards that are AR, if you activate them. The animation side—even though people are more used to the technology now—still blows everyone’s minds and gives people a lot of joy. I would rather be able to make that accessible than making it this fine art, out-of-your-price-range sort of thing.”

Gratz has relocated to Austin, Tex., and recently partnered with the creative studio Mighty Oak to focus on animation and motion graphics for nonfiction television and film. She created the title sequences and many full animations for the 2022 Netflix documentary series about the use of psychedelics, How to Change Your Mind, based on Michael Pollan’s book of the same name.

The AR technology can be used on fine art prints (top row) and business cards (bottom row) alike.

“I animated a mushroom journey of this woman who has cancer and a mushroom journey Michael Pollan did, and the team just let me do whatever I wanted,” she says. “They recognized that my personal style worked perfectly for this.” The series received an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Graphic Design and Art Direction.

And just as she has embraced experimenting with AR art, she is open-minded about new technology when it comes to her work with animation and motion graphics, even exploring the use of AI.

Generative AI art apps like DALL-E and Midjourney have come under scrutiny in recent years for potentially violating artists’ intellectual property. Some artists view AI as an attack on their profession. But not Gratz. She acknowledges the need for better protections for artists but sees AI as another tool, one that still relies on human touch to manipulate it to serve the work at hand. “I’ve used AI for a few projects already in ways that you wouldn’t be able to tell,” she says.

Watch the video to see Gratz’s piece Ultra Violet (2019) come to life.

One example is in a documentary she worked on, In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon. Gratz created graphics for the 2023 MGM+ miniseries. “I used it for one shot, just in a simple way, where we had two frames of Paul singing from a contact sheet. Rather than just fading from one frame to the other, I did a morph,” she says.

The AI program she used was able to track the differences in distance of the facial features in each image to assist with creating that morph. “It was great, but it wasn’t perfect,” she says. She still had to make some adjustments by hand.

“Some people are doomsday about it, but I don’t believe that,” Gratz says. “I’m keeping an eye on it, but it’s been more of a tool for me and, if anything, has made my job faster, which has actually been helpful. I would encourage artists to not be afraid of technology and also to not think that it’s out of their realm of expertise. There are so many ways an artist can use technology to augment their inherent skills and talents.”