Geena Davis: Leading the Fight for Gender Parity in Hollywood

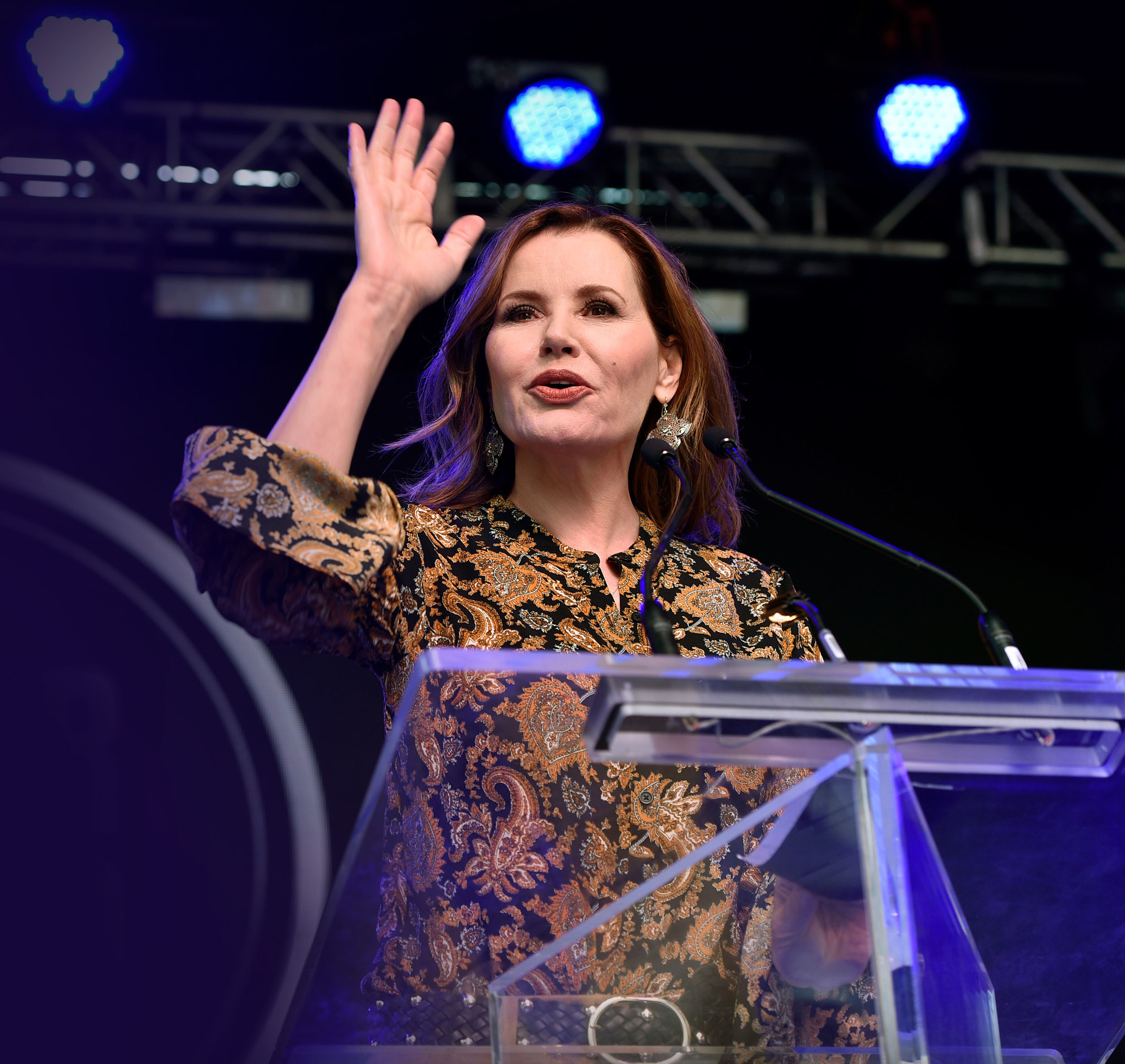

Geena Davis (CFA’79, Hon.’99) speaks at the Share Her Journey Rally for Women in Film during the Toronto International Film Festival, in 2018. In 2004, Davis set out to collect data about the portrayal of girls in media. When she learned that information didn’t exist, she created the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to begin her own in-depth research. Photo by CHRIS PIZZELLO/INVISION/AP

Geena Davis: Leading the Fight for Gender Parity in Hollywood

Long before the #MeToo movement, the Oscar winner, BU alum, and recent GLOW star founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

This article was originally published in Bostonia in February 2020. By Megan Woolhouse.

Excerpt

Sitting in a Pacific Palisades café, eating an Italian grinder on a recent afternoon, Geena Davis recalls when she began talking publicly about Hollywood’s gender problem. It was a delicate proposition for a veteran actor, one with an Academy Award no less, who was hungry to keep landing major roles.

In the early 2000s, Davis had noticed that her daughter, then a toddler, watched TV shows that featured few, if any, female characters. Dismayed, the star renowned for her strong lead roles in films like Thelma & Louise and A League of Their Own used her industry connections with studio executives, directors, and the Screen Actors Guild to launch a conversation about why women and girls were so underrepresented on-screen, or were often represented in highly sexualized ways, and how to fix it.

And who better to address gender bias than a celebrated actor and mother, one with a Mensa membership and the respect of her Hollywood peers? If only it were that simple. Davis (CFA’79, Hon.’99) says that in dozens of private meetings she had with Hollywood stakeholders, men and women, no one was swayed by her observation about women and girls.

“Nobody believed what I was saying,” Davis says, drawing out the word “believed.”

Coming on the heels of the scandals involving Hollywood executives and producers like Harvey Weinstein that have roiled the industry, those words resonate more deeply than ever.

But long before the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements took hold, Davis was hatching a plan.

In 2004, she decided to collect data about the portrayal of girls in media and to build a body of fact-based research that would prove her theory. When she learned that such information did not exist, she created the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to begin her own in-depth research. The institute has used new technology to continuously monitor industry progress toward gender parity. Davis has spent the last 15 years delivering the results to the skeptics, disbelievers, and elite power players who would have been content to let men rule Hollywood. Forever.

Edgy, delicate work

Those results were as bad as, or worse than, Davis thought. In media targeting children age 11 and under, girls were appearing on screen less, and when they did appear they were hypersexualized or they spoke little. One of the institute’s earliest studies found that of the more than 4,000 characters across 400 G-rated, PG, PG-13, and R-rated movies surveyed, women were more than five times as likely as males to be shown in sexually revealing clothing (25 percent for women, versus 8 percent for men). It examined more than 1,000 shows from 12 network, public broadcast, and cable outlets—a total of 534 hours of programming in 2005—finding that male characters appeared at twice the rate of female characters in children’s TV. This was edgy and delicate work, especially in an era when women actors were subjected to one-on-one hotel room interviews.

Now Davis is getting some hard-earned recognition for her efforts to discuss unconscious bias and ingrained stereotypes a decade before they were mainstream concepts. The New York Times has noted that her institute “set the stage” for the Time’s Up movement. And last October, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented Davis with the prestigious Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for her efforts to help change the entertainment industry.

Geena pioneered the field of research on gender in media. Period.

“That’s pretty cool,” she says of the credit she’s been getting for her work, in between sips of an Arnold Palmer and a request to the waitress to box an uneaten portion of her sandwich. Other diners play it cool around the star, dressed in a sweatshirt and sneakers.

Davis, 64, says as a young actor, she encountered “the sort of everyday, garden-variety sexism experience” women in Hollywood have long endured. (She told USA Today in 2019 that a director once asked her to act out a sexy scene sitting on his lap. She did, she said, not realizing that she could say no.)

But, she says, that was “nothing like some of the horror stories my peers have talked about.”

Instead, her feminism was mobilized by a system that denied girls a vision of what they could be beyond the role of a girlfriend or sex object. The institute has even found that when girls and women do get to speak, their dialogue is often about the activities of the men around them.

Davis and her institute have brought their findings to people in the industry—networks, guilds, production companies, and anyone who creates children’s media. The institute holds symposiums, salons, and forums, and Davis notes that she and members of the institute are regular guests at Disney, one of the nation’s largest purveyors of children’s TV and film.

The institute’s commissioned research has also recorded both the strides in gender parity and the areas where work remains. The number of leading female characters in children’s television rose to a historic high between 2008 and 2018—and is now on par with the number of male leads.

But equality is elusive in children’s films, where only about 33 percent of the leading characters are female.

The work has become an absorbing passion for an actor who never planned on being an activist. And it’s spurred new ideas. Davis cofounded the Bentonville Film Festival in 2015 to champion the work of women and underrepresented artists in media. She’s executive producer of the 2019 documentary This Changes Everything, an investigation chronicling decades of gender discrimination in Hollywood.

And she’s open about her desire to take on roles featuring interesting, strong women. Last year, she starred in the third season of the Netflix hit GLOW (Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling), a show about a 1980s women’s wrestling team that was created and produced by women and has a largely female cast. Davis even took the time to write to the internationally syndicated cartoonist who creates Mutts to object to a depiction of worker bees in a recent comic strip as male. (They’re not.)

Launch of a film career

Davis, who grew up in Wareham, Mass., told her parents she wanted to be an actress when she was three years old. She was drawn to music and art, singing in her school choir and learning to play the flute, the piano, and the pipe organ at her Congregational church’s youth services. She asked her music teacher where people go when they want to study acting. He told her BU.

Davis says she felt a bit out of place in BU’s theater-heavy program because she wanted to act in films. After BU, she moved to New York and became a model, appearing in a Victoria’s Secret catalog and on the cover of New Jersey Monthly wearing a bathing suit with a hat over her face.

The catalog image helped Davis land a role in the 1982 Oscar-winning comedy Tootsie, starring Dustin Hoffman. (The part, she says, required her character to appear in her underwear.)

Within a few years, she was starring in major box office productions, like The Fly, opposite her future husband, actor Jeff Goldblum. In 1988 alone, she appeared in three films, Beetlejuice, The Accidental Tourist, and Earth Girls Are Easy.

Earth Girls Are Easy didn’t boost her feminist credentials. But it was easily overshadowed by her Academy Award–winning performance as the wacky dog trainer Muriel, in The Accidental Tourist.

Davis (right) and Susan Sarandon in Thelma & Louise. Photo courtesy of MGM Licensing

Davis had her choice of roles after that, and none won her more fame than Thelma in the 1991 hit Thelma & Louise, the story of two women, hunted by police, and their famous car ride into immortality. Both Davis and costar Susan Sarandon were nominated for Academy Awards for Best Actress that year (Jodie Foster won for The Silence of the Lambs). She says the role changed her life, and her friendship with Sarandon endures. After the film came out, women approached her wherever she went, Davis says, honking and waving at her from their cars and shouting, “Woo-hoo!” like the movie’s characters.

She flashes her famously dimpled smile before getting serious. Yes, the film is ultimately tragic. “We never win, once we get control in the movie,” she says of the characters. “But we never released [control] back to anyone else either.”

Davis says the response to the film was so eye-opening, she decided she would select roles only after considering what women viewers would think of her character. “Will this character give them the opportunity to identify with me and my character and live through that experience? Because it’s really, in my opinion, the best part of seeing a movie,” she says.

A year later, Davis followed up with A League of Their Own, about a professional all-female baseball league in the Midwest during World War II. The star-studded cast included Tom Hanks and Madonna and garnered Davis a Golden Globe nomination for best performance.

Then came a couple of box office failures, Cutthroat Island and The Long Kiss Goodnight. Davis says that as she entered her 40s, the offers to play interesting or meaty roles simply dried up.

“I was appalled and horrified and never would have said anything about it in the press,” Davis says. “You know, you’re supposed to pretend like everything’s great. I think that’s why so many women speak out, whether it’s #TimesUp and #MeToo, who’ve never said anything before. Because it would be a career killer if you complained.”