Sociologist Curington and Students Train as Doulas to Inform Research on Childbirth

This article, by Amy Laskowski and Cydney Scott first appeared in The Brink on April 10, 2025.

“It was a lot,” Curington says. “I felt like I had experienced an injustice, so many lost opportunities during my pregnancy to actually get the support that I needed. And then I started learning about how some of the experiences I had are systemic, and so I wanted to pivot toward this area. I felt like I had this calling afterwards in some ways.”

Curington studies how intersectional oppression (related to race, gender, class, and citizenship) shapes experiences in various environments, including workplaces and neighborhoods. Her own pregnancy inspired her to focus on how it also impacts childbirth. Having hired a Black doula to help guide her, she’s particularly interested in the role these care workers play in tackling racial maternal health disparities and advocating for reproductive justice.

Curington is in the early stages of researching a book on the topic and hopes her work will inform policies that support and uplift these workers. To better understand the issues at play, she’s even trained to become a doula herself—and is encouraging her students to do the same.

“Care work and reproductive labor are literally what creates a community,” Curington says. “It’s so central to make sure that our society can thrive. It’s about supporting communities, and how empowering that can be, and how important that can be for communities that have been historically marginalized and disadvantaged within society. So we need to uplift the voices and uplift the work that these people are doing.”

Care work and reproductive labor are literally what creates a community. It’s so central to make sure that our society can thrive. It’s about supporting communities, and how empowering that can be, and how important that can be for communities that have been historically marginalized and disadvantaged within society.

She says that’s especially vital with society in a key moment where doulas are increasingly recognized for their work and are being incorporated into hospitals around the country (for instance, at Boston Medical Center, BU’s primary teaching hospital, and Mount Auburn and Mass General Brigham).

“What are the joys and the challenges that doulas have in this work?” Curington asks. “What can we learn from their experiences to really think deeply about how to make their work better for them? And how can we think about larger structural changes that need to be in place in relation to doulas’ work as well as the communities in which they serve?”

Inspired by Her Personal Experience

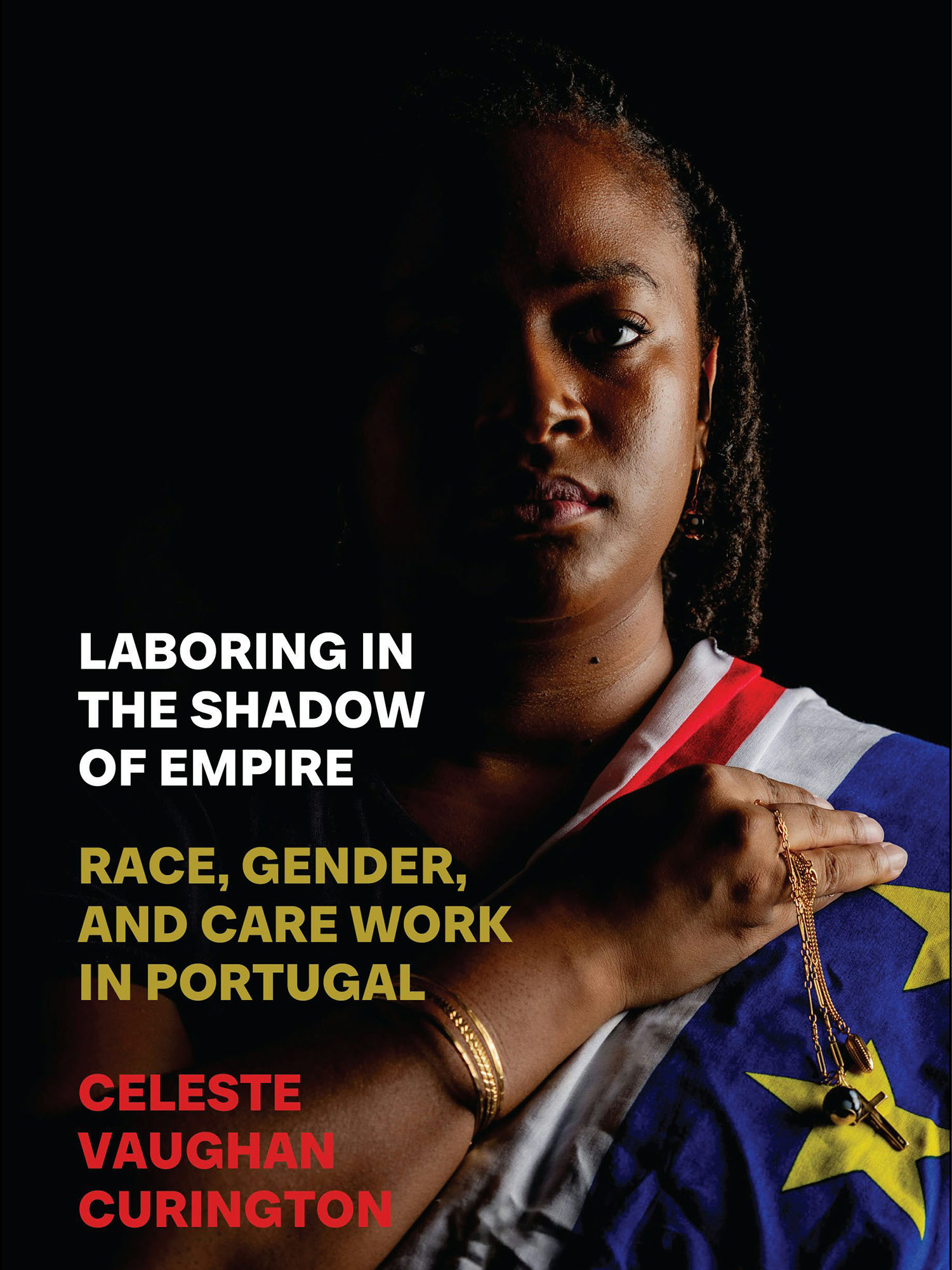

Curington grew up in an immigrant community in New Jersey, a city where 70 percent of its residents had ties to the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central and South America. In her recent book, Laboring in the Shadow of Empire: Race, Gender, and Care Work in Portugal (Rutgers University Press, 2024), she reflects on her family’s history of low-paying, precarious labor, including “hauling slag,” “sharecropping,” and “cleaning house” in rural Tennessee. Sociology, she says, gave her a way to examine and discuss her family’s past and her present.

Curington’s interest in her field was generated during a high school intro to sociology class where she recalls the discussions sparking a nerve with her and her classmates.

“Almost every single student in the class was of color, and…we were given the space to think about our current environment,” says Curington, who went on to get her undergraduate and advanced degrees in sociology. “The class gave us the language and the tools to talk about our own experiences and talk about issues like racism and inequality. It was impactful.”

As a grad student at University of Massachusetts Amherst, Curington became friends with people of Cabo Verdean descent and was invited by the adviser and founder of the school’s Cape Verdean Student Alliance to serve as a grad adviser during their trip to the islands. It was during this trip and subsequent ones, she writes, that she “bore witness to the omnipresent legacies of Portuguese colonialism.”

In Laboring in the Shadow of Empire, Curington explores the experiences of African-descendant eldercare and cleaning workers in Portugal, who have gained citizenship or permanent residency. She investigates how the colonial and racialized labor dynamics make these workers visible in the care and service industries, but simultaneously exclude them from national identity.

“Even though they are hyper visible in homes and on the streets, they [have] the experience of being treated as not truly Portuguese, not really part of that Portuguese national identity of what it means to be a ‘legitimate’ Portuguese person,” she says. “It’s this whole duality between being very visible in terms of the racialization, but also invisible in terms of their belonging and their occupational status.”

To do this work, Curington spent 17 months on and off mainly in Lisbon and Cabo Verde. She rode along with eldercare and institutional cleaning workers on their commutes, observed their home visits with patients and clients, and oftentimes slept in their homes. She weaved together hundreds of hours of participant observations and interviews to show how the gendering and racialization of labor are maintained in local practices today, as African-descendant women care workers live and work under the enduring influence of colonial histories.

Protecting People, Letting Voices Be Heard

In the book’s acknowledgments, Curington credits BU’s full semester of paid parental leave as crucial to finishing her manuscript. After her own parenting journey inspired her sociological study of doulas’ roles in care work in Boston and nationwide—especially Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) doulas—she set out to interview professional doulas working with clients of various racial, ethnic, gender, and class backgrounds. One focus: the challenges the doulas face in a medical system that often ignores and dismisses them and their clients.

In her interviews, many doulas have shared stories of the “medicalization of birth” and the erasure of people’s personal identities, lived experiences, and histories in the delivery room. Her informants gave examples of doctors and nurses performing procedures like cervical checks without asking for consent first. The doctors sometimes ignored their patients when they said they were feeling pain. Doulas also shared experiences of racism and microaggressions in delivery rooms.

Nevertheless, these workers see their role as to protect birthing people and to help make the birthing person’s voice heard. “A lot of them talk about how their role is to ultimately save birthing people, because we know that the maternal infant mortality rate for BIPOC women, both in Massachusetts and nationally, is horrible,” says Curington. “People are literally dying.”

A lot of them [doulas] talk about how their role is to ultimately save birthing people, because we know that the maternal infant mortality rate for BIPOC women, both in Massachusetts and nationally, is horrible. People are literally dying.

However, the data shows that when a midwife or doula attends a birth, the chances of a safer birth are better.

To fully immerse herself in the world she is researching, Curington has trained with several doula organizations, including DONA International (the largest) and Birthing Advocacy Doula Trainings (BADT, a Black-owned, queer-run organization), as well as other queer- and Black-led organizations. She plans to get certified through BADT, which requires doulas to support three births, attend an infant feeding support group, and become certified in infant and children CPR.

“An Unspoken Connection”

Curington is also working with two undergraduate student research assistants on this project. Both have undergone doula training, which they describe as eye-opening. They learned about the science of labor, the emotional toll it takes, and birthing positions to help speed along the process and make things more comfortable for the mother.

Research assistant Sara Diaz (CAS’25) emphasizes the value of having a doula present during labor as an advocate. While doulas don’t have medical degrees, the training has shown Diaz that their experience is invaluable.

“Advocacy work can be giving the birthing person agency,” she says. “What I’ve learned is that birthing can feel like a very isolating experience, especially when doctors are probing around. Having someone there who knows and is experienced in the birthing process, how laborious it is, is very valuable.” What’s more, when a BIPOC doula works with a BIPOC birthing person, Diaz believes “there is a mutual understanding, an unspoken connection where you don’t even have to announce certain concerns—it’s already felt, especially in a hospital setting.”

Birthing can feel like a very isolating experience, especially when doctors are probing around. Having someone there who knows and is experienced in the birthing process, how laborious it is, is very valuable.

As research assistants, Diaz and Nelissa Mascary-Timothee (CAS’25) have been finding studies dealing with intersecting topics within doula research (doulas and surrogacy, for example) and taking notes for Curington so that she can access the papers down the line as she is writing her book. This also helps Curington identify which topics need more scholarship.

Although both students say they don’t have the time to become certified doulas (since they are full-time students), they take their mission seriously. As a Black immigrant woman, Mascary-Timothee says that this research is personal, since she has seen firsthand how healthcare systems don’t always support women like herself who face extra hurdles because of their background, language, and culture. What’s more, she talks proudly of being raised by her late mom, grandma, and aunts, all of whom spent time helping other women in the community.

“I want to help women who look like me get the best care for their bodies and their children,” says Mascary-Timothee, who leads info sessions about the benefits of having a doula at her local community center in Dorchester, Mass. “Growing up with these women made me realize how important women’s health really is.”

When asked why this research is so important right now, Curington becomes impassioned. “The issue is that babies and birthing people are dying,” she says. “It is simply an unacceptable fact to me that birth is literally a battle for many Black women and other birthing people of color. Birthing should be an empowering experience. Birthing is a human condition. It is unacceptable that many of us are scared to give birth, but it’s a fact that this fear is so much more intense for BIPOC folks.”

Their deaths are largely preventable, Curington says, and she believes doulas are motivated by this reality. Curington hopes her research can help doulas get the payment and support they are due.

“They are taking on a lot of trauma and a lot of emotional labor in order to get this work done,” she says. “I’m interested in care work, which tends to be marginalized, underpaid, and not as respected. We need to flip that and highlight what many care workers already know or birth workers already know—that the work is extremely valuable for communities.”