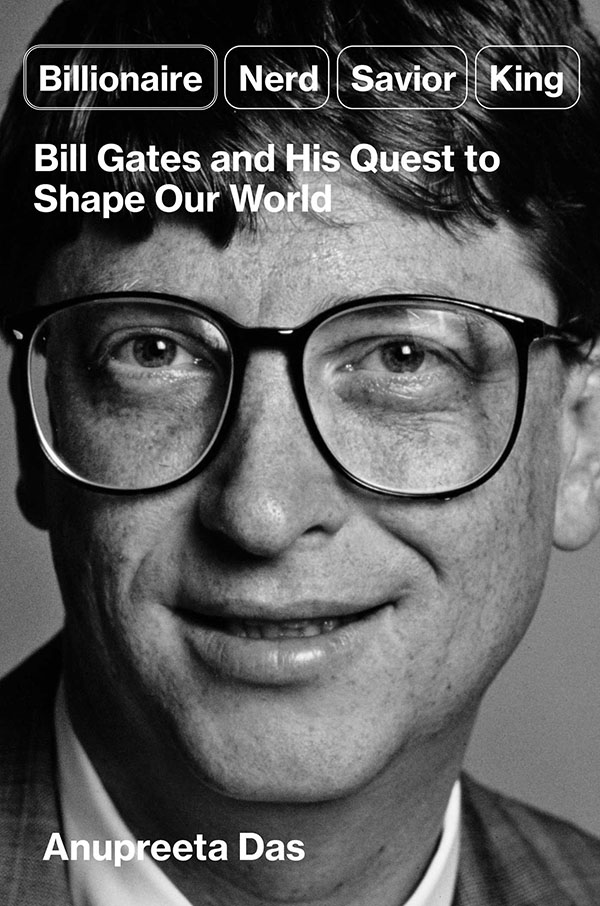

Photo by Michael Lionstar.

Journalist Anupreeta Das Takes Readers Behind the Billionaire

In her new book, the New York Times finance editor explores the many facets of Bill Gates

As reporter Anupreeta Das covered Bill Gates over the years—first at the Wall Street Journal, and then at the New York Times where she is the finance editor—she became fascinated by the billionaire Microsoft founder’s many personas: genius, tech tycoon, philanthropist.

A May 2021 Times article about alleged sexual and other workplace harassment by Gates’ money manager, which Das (’07) cowrote, hinted at Gates’ complex public image, stating, “Mr. Gates’s reluctance to take decisive action…adds to an emerging portrait of the billionaire philanthropist that is at odds with his image as a roving global do-gooder and champion of women’s empowerment.”

That same month, Das covered the divorce of Gates and Melinda French Gates. “That’s when I began thinking about, ‘Who is this guy?’” says Das. “We kind of venerate him. He’s this philanthropist with this kind of unimpeachable profile.” Yet, before news of the divorce broke, there was already reporting on his alleged extramarital affairs and his connections with Jeffrey Epstein, the financier who was accused of sex trafficking. “So I began questioning. Who is this person? And what is it about our fixation with billionaires? What does it say about us?”

Das grapples with these questions in her forthcoming book, Billionaire, Nerd, Savior, King: Bill Gates and His Quest to Shape Our World (Simon & Schuster, 2024), due out on August 13.

The “Dark Side” of Philanthropy

“Gates was an early template for that nerdy, boy-genius, tech founder—super socially awkward, but also brilliant, and then they changed the world,” says Das. But “then he represented the worst of capitalism in the 90s, when Microsoft was accused of being a monopoly and Gates was often portrayed as this ruthless, Rockefeller-style, robber baron. That was another iteration.”

Das also delves into how Gates became a full-time philanthropist and changed how he was viewed in the public eye. “Here’s a guy with billions of dollars giving money away, changing how philanthropy works. How could you say anything negative about Gates? So that’s kind of the ‘savior’ and ‘king’ aspect of it,” says Das.

However, she examines the “dark side” of philanthropy, exploring how large-scale, institutionalized philanthropy can shape social and political agendas. “Even if that’s not your intention, it’s just the fact that money buys influence,” she says.

For example, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is one of the largest donors to the World Health Organization. She points to the example of the Gates Foundation funding efforts for polio eradication. “The foundation has done a lot of great work, but because it has so much money, it could shape the agenda. It can actually influence global health priorities,” Das says.

“Who is this person? And what is it about our fixation with billionaires? What does it say about us?” —Anupreeta Das

Anupreeta Das

She also discusses the potentially disingenuous aspects of “big philanthropy” and its image-remedying capabilities. “Philanthropy has always been a way for a lot of wealthy people to try to build themselves up in a certain way,” Das says.

She examines The Giving Pledge, a charitable campaign started by Gates and Warren Buffett, which encourages the world’s wealthiest to pledge the majority of their wealth to charity. While Mackenzie Scott, ex-wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, has given away more than $16 billion to charity since signing the pledge, the Giving Pledge has still come under scrutiny for its lack of enforcement. “At its worst, the criticism is that it’s nothing more than a PR exercise for billionaires to show how humble and generous they are with all these commitments to give their fortunes away,” Das says. “But how can we assess if there’s anything good that’s come out of it? Because it’s not measurable. It’s just something people write to say, ‘I’m committed,’ and then there’s no way to actually hold people to their words.”

The Man and the Money

Das describes her reporting for the book as “outside-in,” starting with a lot of research on the subject, followed by reaching out to sources on the outermost fringes of Gates’ circle. “I think the best way to test your own hypotheses is to reach out to people,” she says. “Usually what I do, and this is for any reporting, is to reach out to people who are in the orbit, but at the furthest extremes, because they are likely to have insight, but also aren’t that close that they end up being bound by non-disclosure agreements.” She worked her way closer to Gates from there, including interviews with current Gates Foundation employees. (She did not speak with Gates himself.) “Ultimately, the goal is, by the time you get to the person who you’re writing about, you should have your information strong enough that it is hard for the person to deny.”

Das’s reporting reveals much about the US’ financial, social, and political landscapes. First, she looks into what has caused the immense growth in the number of billionaires. Whereas there were just 66 billionaires in the US in 1990, in 2023 there were more than 700. “But my biggest discovery, which was already a hunch, is just how much influence billionaires have on our lives,” she says, again citing Gates’ influence on the World Health Organization. She also investigates the social privilege at play in the making of many billionaires. “We celebrate billionaires. We kind of think of them as the apex of the American dream, right? Hard work, luck, talent, upward mobility.” Yet, she looks into why a large number of the Forbes “World’s Real-Time Billionaires” list are white men. “You have to address systemic advantage when you’re thinking about these success stories,” she says.

“I try not to be prescriptive, not to say, ‘Oh, this is what we must do,’” says Das.” Rather, I try to get people to think about all of these ways that we don’t connect wealth and inequality.”