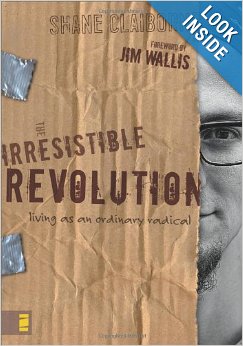

The Irresistible Revolution, by Shane Claiborne

Shane Claiborne. The Irresistible Revolution: living as an ordinary radical. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2006.

Book Review submitted by Xochitl Alvizo, Ph.D. Candidate in Practical Theology, Concentration: Congregation and Community

“Growing smaller and smaller until we take over the world,” is the title of the second to last chapter in Shane Claiborne’s book The Irresistible Revolution: living as an ordinary radical. I begin here because there is an important question this title raises for me – and the assumption that I think it makes. Let me first offer a quick introduction to Claiborne’s book.

Shane Claiborne understands himself to be living the “ordinary” life of a Christian. And, in as much as his life and the life of his community is countercultural and gets to the root of what it means to be a Christian disciple, then he would also agree that he is an ordinary radical (130). Claiborne retells the story of how he left his status as a “cool” person and his comfortable life in order to become a charismatic Jesus freak (41). However, “the fiery newness of it died out,” and soon Claiborne found himself disillusioned and wondering “if anybody still believed Jesus meant those things he said” (45, 72). Claiborne explains, “we were not going to win the masses to Christianity” unless people actually began to live it. In order to learn what a “fully devoted Christian looked like, or if the world had even seen one in the last few centuries,” Claiborne set on a journey in search of a Christian (I can’t tell if he is being facetious or not, but those are his words, 71-72). His search for a Christian first takes him to Calcutta to work with Mother Teresa; this begins his new understanding of Christianity, of the life of a Christian, and what it means to be the church. His book is an autobiographical retelling of the development of his theology and of the community of which he is a founder, The Simple Way.

Two things that are central to Claiborne’s theology and ecclesiology are 1) the church in Acts where it is recorded that there were no needy persons among them and, 2) the kingdom of God “on earth as it is in heaven” (64). These two themes run throughout the book and their importance is evidence in the very direct ways that Claiborne’s life in community is lived with, and as part of, people who are economically poor. However, there is also another theme that runs throughout the book and similarly grounds Claiborne’s theology but does not seem to be compatible with it. One of the lessons Claiborne states to have learned from Mother Teresa was that “the temptation to do great things is always before us;” for this reason Mother Teresa stressed the importance of doing “just small things” (78). Thus, Claiborne learns to see miracles in the small things, in acts of love. He takes heart in the movement he sees among younger evangelical Christians, of which he sees himself a part, and which he experiences to be a “gentler revolution” (313). In the end though, Claiborne wants to grow smaller and smaller “until we take over the world.” The chapter starts off expressing the sentiment of the first part of that phrase – the gospel does not draw a crowd, people are not inclined to line up for the cross – but then the language (and the metaphor) changes. In the last six pages of the book Claiborne affirms that Christians are not called to be candles but fire, “so that the Spirit’s inferno of love spreads across the earth” (352). It seems subtle, perhaps insignificant, maybe even paranoid, but it is grand visions such as this one that may make the difference between understanding oneself as a participant in something Divine because one judges it to be worthy of one’s commitment, and understanding oneself as the ones responsible to bring about the divine plan. Claiborne says that Jesus points the church to its “true identity,” that is, to live close to those who suffer (160), but why must he also aspire to “win the masses,” to take over the world? I cannot help but think it rings of Christendom, of empire, and of the very kind of system of domination that produces the suffering to which Jesus’ good news speaks. I wonder about the witness this kind of theological undercurrent makes to people who are all too familiar with the sins of the church.

View all posts