Modern Muckrakers: Investigative Reporting and Corporate Factory Farming

Trinity Olander

Instructor Introduction

Trinity Olander wrote this critically aware research paper for WR 152: Rebellious Journalists of American Counterculture, a course in which we challenge journalism’s pragmatic approach and investigate what prompts change to the genre. In part inspired by her dedication to environmental advocacy, Trinity ambitiously and courageously dismantles the narrative façade disseminated by big corporations on factory farming. Through a sustained, poignant analysis rooted in American journalism’s Muckraking tradition, she dissects both how Corporate America wittingly shields the public from factory farming’s gruesome reality, and the historically effective strategies modern-day journalists can implement in order to elicit real, important change. Her passion for advocacy shines throughout her impressive insights, which are, of course, buttressed by extensive research. I am proud to say that environmental activism has gained a powerful new voice in Trinity.

Sam Sarkisian

From the Writer

In this essay, I investigate the conflict between investigative journalism and corporate manipulation surrounding the crisis of modern animal agriculture. It delves into the historical evolution of activism, the economic and legislative influence wielded by corporations, and the subsequent challenges faced by journalists and activists in exposing the truths of industrial farming. Highlighting the role of emotional storytelling and subjective reporting, it discusses the efforts of authors like Jonathan Safran Foer in rebuilding the narrative around factory farming. The essay scrutinizes corporate Machiavellianism through Ag-Gag laws and deceptive marketing tactics while advocating for a more transparent discourse on the ethical and environmental implications of industrial agriculture. It also examines the societal consequences of corporate dominance, including widespread ignorance and complacency among consumers. By drawing parallels to historical movements like the Muckrakers, the essay underscores the importance of modern journalism in challenging corporate hegemony and fostering public awareness. It concludes with a call to action for journalists and citizens to reclaim agency in shaping the future of food production and animal welfare.

Modern Muckrakers: Investigative Reporting and Corporate Factory Farming

“They use everything about the hog except the squeal” (Upton Sinclair The Jungle 38). Beginning with the industrialization of farms in the early 20th century, nearly all farm animals including cows, pigs, turkeys, and fish live in large industrial farms. Animal suffering and the atrocities that result from this farming model are overshadowed by corporate profit produced by the unprecedented billions of pounds of meat that exit farm doors each year. Over the years since the farms’ inception, some journalists have attempted to paint this gruesome scene for the public eye, but large businesses that reap the profits have fought back. For decades, major corporations have puppeteered legislation and the media to sustain factory farming enterprises. Their history of silencing journalists and activists calls for a new approach to journalism based on emotional storytelling, reporting methodology, and the use of varied mediums to convey subjectivity. Author Jonathan Safran Foer of Eating Animals utilizes this innovative journalism style which is now indispensable to the anti-factory farming movement.

CORPORATE MANIPULATION AND LEGISLATIVE CONTROL

Before we can dissect the role of investigative journalism that mirrors the muckraker style as a remedy for corporate manipulation, it is critical to establish how corporations have sustained the factory farming enterprise by economically controlling the government and media. Major corporate businesses and political powers have molded into a symbiotic relationship of mutual economic benefit. As a result, the influence of policymakers versus corporate businesses on public law is virtually indistinguishable. The most obvious way in which businesses have taken explicit legislative control is what have been dubbed “Ag-Gag laws.” According to Pamela Fiber-Ostrow and Jarret S. Lovell—authors of an essay that reveals the truth behind how corporations conceal factory farms—these laws, that took root in Kansas in 1990, “prohibit visual and sound recordings at meat and dairy farms, [and] make it illegal for job applicants to fail to disclose affiliation with an animal advocacy organization,” (Fiber-Ostrow and Lovell “Behind a Veil of Secrecy: Animal Abuse, Factory Farms, and Ag-Gag Legislation” 231). Therefore, upon the advent of these laws, activists and journalists could be criminally prosecuted for attempting to expose the horrors of factory farms. This is unlike the case for the Humane Slaughter Act, which to date no one has ever been prosecuted for violating despite obvious infractions (Fiber-Ostrow and Lovell 237).

Beginning in February 2013, activists and journalists have been met with legal prosecution. In 2013, Amy Meyer became the first victim of Ag-Gag legislation while attempting to record at a Utah meat packing company. She refused to stop after being asked by a managing employee and was thereafter charged in court (Fiber-Ostrow and Lovell 231). Meyer was the first—but certainly not the last—to be prosecuted. Today Ag-Gag laws still exist in Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Montana, and North Dakota. Other states have enacted similar legislation or have attempted to pass Ag-Gag laws but were met with activist lawsuits that postponed efforts. Those states include Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, among others (Pepin “What Are Ag-Gag Laws and How Many States Have Them?”). Therefore, journalists now have the potential to face real, life-altering repercussions for their work as a result of corporate control.

Beyond Ag-Gag laws, corporations have also found more deceitful techniques to feign transparency to the public, and directly undermine journalism initiatives that are rooted in exposure and truth-telling. Investigative reporter, Jan Ditkiewicz, went on a research expedition to a farm called “Fair Oaks Farms” in Indiana. This farm’s main attraction is not the animals (which are located on a site a bus ride away), but the pig-themed shops, food sites, and family activities such as a bustling petting zoo. For those interested in seeing a real pig, Fair Oaks offers a bus to the local farm where they embark on a guided tour that highlights pig socialization, and exquisite animal welfare policies. At the end, the tour is topped off with a meet and greet with the farm’s resident baby pig. However, the reality is that Fair Oaks “relies on both the tropes of alternative farming tourism and on strategic revelation—including literal glass walls—to craft a publicly palatable narrative about factory farming and factory-farmed animals” (Dutkiewicz “Transparency and the Factory Farm” 19). The farm builds upon narratives of the “small-family-farm” ideal sustained by many unknowing Americans, and intentionally demonstrates that factory farms are merely a larger, more efficient version of these small farms. In doing so they “[flip] the script” on activists by using their calls for transparency against them (Dutkiewicz 19). This builds yet another limitation for journalists and activists, as it means they must formulate their work in a way that opposes the narrative of corporations and exposes why their “transparency” is not the reality.

Furthermore, journalists must combat the deceptive language used by corporations that the public has been conditioned to use and accept. According to Pamela Fiber-Ostrow and Jarret S. Lovell, “Even the names of our meats conceal their origins. We eat ‘beef’ rather than ‘cow,’ ‘bacon’ rather than ‘pig,’ and ‘chicken’ rather than ‘a chicken’” (Fiber-Ostrow and Lovell “Behind a Veil of Secrecy: Animal Abuse, Factory Farms, and Ag-Gag Legislation” 234). In essence, then, the truth of what society is eating is inherently “hidden in plain sight” (Fiber-Ostrow and Lovell 234). This euphemistic language creates a barrier that dissuades critical thinking on where distributed meat products come from. Thus, a reformed style of language is necessary to discuss factory farms. Rather than adhere to traditional diction and straightforward facts, Jonathan Safran Foer utilizes personal anecdotes and first-person language—such as in declaring, “I love sushi, I love fried chicken, I love steak. But there is a limit to my love”—to make the story less concentrated on the bare facts (Foer Eating Animals). Rather, Foer emphasizes why the public must reflect on their own beliefs and practices as they relate to the food they consume and the media information they accept as fact. Through this method of subjectivity, it is possible to begin dismantling the preset narratives corporations have disseminated to the public in order to boost their own initiatives.

A SOCIETY OF IGNORANCE

As a result of unchecked corporate manipulation, the public is unaware of the stakes of the farming conflict, and in turn, there is limited public discourse surrounding the issue. Subjective journalism is a critical remedy to this absence of discussion. Because the farming issue relies so heavily on legislative reform to enact change, public discourse is a necessary stepping stone to usher the path toward reform. In this case, a disinformed public is a stagnant society. To evaluate the scope of public knowledge on the issue, S. Plous held a survey in 1993 where he instructed respondents to indicate which of 13 day-to-day products contained some sort of animal product. Some of the items mentioned included butter, chewing gum, and crayons. The results found that the mean of correct answers was 2.8 and the highest number stated was 6. However, in reality, all 13 products contained animal ingredients (Plous “Psychological Mechanisms in the Human Use of Animals”). While some of these products are notably less obvious than others (such as a crayon), it was disconcerting that so many respondents were unaware of the animal ingredients in more obvious items like butter. This ignorance is a direct consequence of corporate control over the narrative and what information is deliberately concealed from the public.

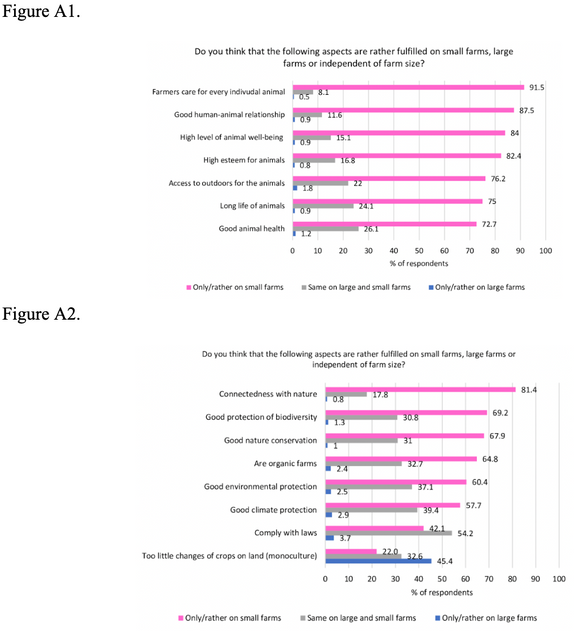

A similar study was conducted in May of 2021 by Gesa Busch, where they recruited 985 subjects to answer a variety of questions about their perceptions on farming. The study found that 75.8% of respondents demonstrated a preference for “small” over “large” farms, and that: “negative media reporting on animal farms (remembered by 92%) is more frequently related to large farms (82.5%) whereas positive media reporting (remembered by 81.4%) are mainly linked to small farms by 56.8%” (Busch et al. “‘Factory Farming’? Public Perceptions of Farm Sizes and Sustainability in Animal Farming”). (See Figures A1, A2, A3). These public perceptions were a consequence of the “small-is-beautiful” narrative that has been promoted by corporate-dominated media forums as a placeholder for the real conflict. The real conflict is not which farms are small or large, but rather what farms are industrialized and which are traditional family farms (which are now effectively nonexistent). According to Jonathan Safran Foer:

It shouldn’t be the consumer’s responsibility to figure out what’s cruel and what’s kind, what’s environmentally destructive and what’s sustainable. […] We don’t need the option of buying children’s toys made with lead paint, or aerosols with chlorofluorocarbons, or medicines with unlabeled side effects. And we don’t need the option of buying factory-farmed animals (Foer Eating Animals).

Corporations not only provide these “options” to citizens but actively promote unsustainable practices and unfounded facts. The narrative of “small vs. large” is a key example of these means of distraction and promotion. There is no scientific correlation between farm size and environmental repercussions. Instead, conflicts of animal welfare and climate effects are the result of many other factors that stem from industrial farm systems, like improper waste disposal and unethical animal maintenance. However, because media platforms are restricted by corporate control, the public has been led to believe that “large” farms are the problem and are less sustainable.

Despite the media coverage that has come about throughout factory farming’s recent history, many individuals still live in ignorance, blindly abiding by the story that is fed to them by corrupt media. This acceptance and indifference, according to Nancy M. Williams—a philosopher who studied at the London School of Economics— is the result of “affected ignorance,” which is the act of individuals explicitly choosing not to investigate the morality of the practices they participate in (Williams “Affected Ignorance And Animal Suffering: Why Our Failure To Debate Factory Farming Puts Us At Moral Risk”). This, in turn, leads to “Failing to develop a critically reflective consciousness [that] can perpetuate institutional systems, practices, and discourses that are cruel and corrupt” (Williams). This clear-cut idea of affected ignorance indicates the psychological consequences that occur when the media drives a false narrative. Similarly, the concept demonstrates how the media has played a direct hand in hindering widespread public discourse. When individuals wish to believe in the ideal farm, the media can then use these hopes (and fears of the real truth) to fabricate the narrative that corporations want the public to keep believing. When consumers do not critically investigate the origins of their food, the trust falls in the hands of the businesses that their standards of welfare are up to par. To remedy the cultivation of affected ignorance, Foer’s subjective voice promotes critical thinking about the origin of meat and poultry products. Among his reflections about his relationship with food and how his perceptions have changed throughout his life, Foer declares:

We can’t plead ignorance, only indifference. Those alive today are the generations that came to know better. We have the burden and the opportunity of living in the moment when the critique of factory farming broke into the popular consciousness. We are the ones of whom it will be fairly asked, ‘What did you do when you learned the truth about eating animals?’ (Foer Eating Animals).

Foer’s differentiation between “ignorance” and “indifference” is essential in encouraging reflection. Blindly accepting “facts” as the media supplies them can lead to a false sense of security. This “indifference” arises when citizens lack the resolve to critically investigate their practices. Foer instead promotes accountability and reflection, even in the face of unwavering corporate influence and manipulation.

ORIGINS OF CORPORATE DOMINANCE

The threat of enormous money-hungry corporations is not one that abruptly emerged over the past few decades, but rather, has been brewing since the advent of the nation. This has built a powerful force for journalists to combat when reporting on the factory-farming issue and calls for a new style of writing to combat such a powerful entity. Thomas Jefferson declared in the early 19th century: “I hope we shall crush… in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of our country” (Nichols “Thomas Jefferson Feared an Aristocracy of Corporations”). Despite these declarations, the symbiosis of corporations and the American government has only inflated over time. One of the earliest movements to combat corporate power was with the “Muckrackers,” a term coined by Theodore Roosevelt during his presidency. This group of writers began with Nellie Bly in 1864, who went undercover in a women’s insane asylum to expose the atrocities behind closed doors. Afterward, there were others like Demarest Lloyd (author of Wealth and Commonwealth in 1896 to expose monopolies), David Graham Phillips (author of 1906 The Treason of the Senate highlighting political corruption), and Upton Sinclair (author of The Jungle which shed light on Chicago packinghouse working conditions) (“Muckrakers” American Economic History: A Dictionary and Chronology 409). Together they set the stage as the first examples of writers who cultivated exposés of corporate schemes. Likewise, the early methods of the Muckrackers set the stage for the modern methods journalists and activists employ to bring public attention to critical issues. According to James S. Olson and Abraham O. Mendoza, who authored a detailed timeline of the economic history of America: “Muckraker journalism provided the Progressive movement with much of the emotional ammunition it needed to implement federal and state reform legislation in the early 1900s” (“Muckrakers.” American Economic History: A Dictionary and Chronology 409). Therefore, even beginning as early as the dawn of the 20th century, journalists have been using emotions to appeal to the greater public about critical societal issues. However, if anti-corporate efforts began as early as the Muckraker era, why since that age, have journalists fallen through the cracks while trying to report on issues like factory farming? In reality, corporations and their political influence, as well as standards for traditional journalists, forced many Muckrakers and early investigative journalists to silence. A revised method of journalism is necessary to compete in the modern stage.

THE TRADITION OF OBJECTIVITY

By building upon the methods used by Muckrakers, modern journalists can dig deeper into emotions and subjective experiences. However, it is important to discuss that along with corporate manipulation, modern journalists must also contend with historical expectations of objectivity. Works such as Eating Animals contend with the traditional expectations of journalists like those outlined in Kovach and Rosenstiel’s Elements of Journalism, where they provide a detailed breakdown of traditional values journalists must uphold to be considered truthful and legitimate. In particular, they highlight ten explicit “elements” which they deem most important, including but not limited to an obligation to truth, loyalty to citizens, independence from the subject, and an obligation to exercise personal conscience (Kovach and Rosenstiel The Elements of Journalism xxvii). These expectations limit the capacity of journalists to incorporate subjectivity into their work because they run the risk of being considered untruthful or partial. However, emotions are the very basis of how individuals form their opinions and moral ideations, and are therefore not only acceptable, but should be an expectation of modern journalists. According to Tom Wolfe, a journalist and critic who focused his commentary on New Journalism, “It is the emotions, not the facts, that most engage and excite readers and in the end are the heart of most stories” (Wolfe “The Emotional Core of the Story” 151). It is critical to dismantle perpetuated standards of objectivity, to instead give journalists the capacity to include emotional elements in their work that combat corporate dominance.

Nonetheless, some critics, like Jay Rayner condemn Foer’s emotional tone, writing it off as unprofessional and unfounded. Rayner in his book review published in The Guardian, criticizes Foer’s expression of his “wide-eyed shock and disgust” as he learns new information about the factory-farming industry (Rayner “Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer”). Rayner claims that because this information has been accessible for many years, it is nonsensical that Foer would just now experience these emotions of intense rage and distress for the first time. However, the mere fact that Foer—late enough in his life that he is now a father—was just initially becoming aware of these issues at the time of his writing, is a testament to the lack of public knowledge surrounding this issue. Furthermore, the average citizen is unlikely to easily discover these facts without undergoing their own intensive research and interviews. Thus, Foer’s subjective style also serves as a roadmap for others to replicate his journey of self-discovery, in a manner that has been robbed from citizens by corporate corrupt media.

SUBJECTIVITY IN FILM

Beyond written accounts like Eating Animals, visual media is a critical tool in amplifying the subjective, emotional elements of journalism vital in opposing the factory farming industry. Like many other examples of investigative reporting surrounding the conflict, journalists in the past few decades were not the first to use strategies like visual journalism. Early Muckraker photojournalists such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine used similar methods by taking photos directly of their subjects. For instance, Riis published a now famous photography book titled How the Other Half Lives which included 1890 images from New York City “slum” neighborhoods. He used the newly invented flash photography to capture these scenes never before available to the public (see Figures B1, B2). However, with corporations taking control over the media and with the advent of Ag-Gag and similar laws, visual journalism has become less forthright. In modern works of visual media surrounding factory farming, the films use not only direct videography but also techniques to emphasize the emotional elements of the stories. One of the earliest films discussing factory farming was Life Behind Bars, created in 2002 with narration by Mary Tyler Moore. In the film, Moore addresses the camera directly, explaining that the animals in factory farms were suffering and there was a total lack of legislation at play concerned with their welfare. Her narration is supplemented with footage of animals within the farms, locked in cramped cages and exhibiting distressed behaviors. Moore describes “gestation crates,” “battery cages,” and “veal crates,” and how these barbaric cages were utilized to maximize farm efficiency (Moore Life Behind Bars). Woven throughout Moore’s narration are tone fluctuations and vocal emphasis that highlight particular points, making clear Moore’s contempt for what she is reporting. This style of narration is highly subjective, but is necessary to understand the magnitude of the issue. If Moore were to speak in a neutral tone, the narration would produce little to no psychological reaction: the issue would not appear as urgent. Humans connect to movies and TV shows because they can directly see and hear the person speaking to the camera; the same effect initiated by the direct narration.

A similar emotional effect is evoked by the film reimagining of Foer’s Eating Animals. In this longer film produced by Christopher Quinn in 2017, many analogous techniques to Moore’s are used, such as incorporating direct footage from within the factory farms and video interviews with numerous subjects that Foer originally canvassed for his book. This time, however, the individuals are being directly pictured, and emotional signals like tone and vocal emphasis become apparent. Early in the film, a man named Paul Willis is introduced as the founder of the Niman Ranch Pork. Co., one of the only true small farms still in business in the industrialized meat industry. Footage is displayed of Willis engaging in his day-to-day operations; footage which takes on a distinct effect compared to the images of pigs’ bodies on large packing lines shown just a few minutes prior. Paul Willis was originally interviewed for Foer’s book. However, in this case, the interview is filmed and a face can be put to the words. Willis describes:

When I first started raising pigs in the ‘70s, I went to meetings, and, you know, they told me you gotta get bigger or get out. And they showed me these buildings and how you could put one of these up and how many animals you could raise and all this kind of thing. I just had to visit one of those buildings once to realize that I…I just… I just did not wanna raise animals like that (Quinn et al. Eating Animals 22:20).

This first-hand account stresses the horrors of industrialized farms, coming from an individual whose livelihood relies on animal slaughter. Even from his perspective, industrial farming is inhumane. A similar perspective is given by another small farmer named Bill Niman, owner of BN Ranch. Shortly after Willis’ account, Niman is pictured indicating to one of his fields and a pack of cattle, when he says: “This is what it means when they say the grass is always greener…The meat industry has done a good job of disconnecting eating meat from killing animals and it’s really made it possible for people to not fully appreciate that there… actually is an animal that had to be murdered for them to eat this” (Quinn 24:10). This obvious, yet often forgone connection between eating animals and animal murder, is emphasized by Niman’s direct narration. The connection plays an important role in the conversation to dismantle corporate attempts to draw a gap between awareness of the food that citizens eat and where it comes from. While this notion is outlined in Foer’s book, it is further emphasized by the direct interview account. According to Carl Plantiga for the Oxford Academic: “Emotions in movies are elicited chiefly in relation to narrative situations refracted through various sorts of character engagement that ensure investment in the narrative and an orientation to narrative events” (Plantiga “The Affective Power of Movies”). Therefore, when consuming journalism in the form of a film, it elicits a physiological response to the emotional elements that would not be experienced to the same extent as reading words on a paper. This mechanism for conveying subjectivity is critical in the context of the factory-farming issue because public discourse first relies upon personal reflection and identifying in what ways citizens themselves are complacent.

The threat of corporate greed and economic desires has been developing throughout American history and is implicated in every crossroad of American society and government. Since its inception, the corporate-manipulation force has become a threat to public health, environmental justice, climate change, animal welfare, and more. In the words of Sinclair: “The great corporation which employed you lied to you, and lied to the whole country—from top to bottom it was nothing but one gigantic lie” (Upton Sinclair The Jungle 91). The public, however, proceeds unaware of the lies that encircle them, due to a motley of innovative tactics corporations have cultivated to camouflage their corruption.

Nonetheless, modern journalists have the opportunity to fight back. Using an emotive style rooted in the legacy of early American Muckrakers, Jonathan Safran Foer and others who follow him can begin to shed light on the truth and pave the way for public discourse. As the public evolves, new and innovative solutions to the factory-farming conflict—like in-vitro, artificial meat production (which produces protein without a need for animal slaughter)—have the opportunity to gain leverage and funding that corporations otherwise prohibit. Now is the chance for journalists and citizens to flip the script yet again, and take power back into the hands of the people. And the hogs.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Works Cited

Amelinckx, Andrew. “Unwinding the Overturn of Idaho’s ‘Ag-Gag’ Law.” Modern Farmer, 2 Oct. 2018, modernfarmer.com/2015/08/idaho-ag-gag-law-overturned/.

Busch, Gesa, et al. “‘Factory Farming’? Public Perceptions of Farm Sizes and Sustainability in Animal Farming.” PLOS Sustainability and Transformation, vol. 1, no. 10, 2022, p. E0000032.

“Cafos in the US.” CAFOs in the US, cafomaps.org/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023. Dutkiewicz, Jan. “Transparency and the Factory Farm.” Gastronomica, vol. 18, no. 2, 2018, pp. 19–32.

Editors, Biography.com. Jacob Riis – How the Other Half Lives, Photos & Facts – Biography, www.biography.com/authors-writers/jacob-riis. Accessed 17 Nov. 2023.

EPA. “NPDES CAFO Regulations Implementation Status Reports | US EPA.” United States Environmental Protection Agency , www.epa.gov/npdes/npdes-cafo-regulations-implementation-status-reports. Accessed 17 Nov. 2023.

Fiber-Ostrow, Pamela, and Jarret S. Lovell. “Behind a Veil of Secrecy: Animal Abuse, Factory Farms, and Ag-Gag Legislation.” Contemporary Justice Review : CJR, vol. 19, no. 2, 2016, pp. 230–249.

Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. CROWN, 2021.

Nichols, John. “Thomas Jefferson Feared an Aristocracy of Corporations.” The Nation, 4 Jan. 2016, www.thenation.com/article/archive/thomas-jefferson-feared-aristocracy-corporations/.

Olson, James S. and Abraham O. Mendoza“Muckrakers.” American Economic History: A Dictionary and Chronology, 2015, pp. 408–409.

Pepin, Ivy. “What Are Ag-Gag Laws and How Many States Have Them?” Thehumaneleague.Org, 7 June 2022, thehumaneleague.org/article/what-are-ag-gag-laws.

Plantinga, Carl, ‘The Affective Power of Movies’, in Arthur P. Shimamura (ed.), Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies (New York, 2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199862139.003.0005, accessed 14 Nov. 2023.

Plous, S. (1993), Psychological Mechanisms in the Human Use of Animals. Journal of Social Issues, 49: 11-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00907.x

Quinn, Christopher, et al. Eating Animals. Ro*Co Films, 2017.

Rauch, Joseph. “What Are Animal Products and Byproducts?” Public Goods, 16 July 2020, blog.publicgoods.com/what-are-animal-products-and-byproducts/.

Rayner, Jay. “Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer | Book Review.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 28 Feb. 2010, www.theguardian.com/books/2010/feb/28/eating-animals-jonathan-safran-foer.

Richman-Abdou, Kelly. “Jacob Riis: The Photographer Who Showed ‘How the Other Half Lives’ in 1890s NYC.” My Modern Met, 30 July 2020, mymodernmet.com/jacob-riis-how-the-other-half-lives/.

Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle. First Avenue Editions, 2016.

Williams, Nancy M. “Affected Ignorance And Animal Suffering: Why Our Failure To Debate Factory Farming Puts Us At Moral Risk.” Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, vol. 21, no. 4, 2008, pp. 371–384.

Wolfe, Tom. “The Emotional Core of the Story .” Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers’ Guide from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, Plume, New York, 2007.

Trinity Olander, a sophomore enrolled in the Cellular, Molecular & Genetic Biology program within the College of Arts and Sciences, hails originally from Red Bank, New Jersey. Fascinated by research in synthetic biology, Trinity’s interests extend to the realms of animal welfare, environmental preservation, and public health. She seeks to explore how advancements in synthetic biology can serve as a catalyst for positive change, while also delving into the symbiotic relationship of this discipline with written and multimedia advocacy. She believes that bridging this gap is the key to galvanizing change. Trinity wishes to extend her enduring gratitude to Professor Sarkisian, whose mentorship has profoundly influenced her academic and personal journey, shaping her perspectives both as a student and as a developing writer.