Earthquake, Thunderbolt, Fire, Father: Community and Catastrophe in the Wake of 3/11

Roshan Sivaraman

Instructor’s Introduction

Roshan Sivaraman has created a gorgeous and provocative essay in WR 152, American Environmental History. I particularly appreciate their extremely skillful introductory structure in this essay about the massively destructive 2011 Japanese earthquake that subsequently threatened the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Their assessment measured American and Japanese public and media reactions, offered clear background context, and dealt effectively with the numerous complexities of their topic. In proposing the topic, they wrote, “I am interested in researching cultural responses to both ‘natural’ and ‘man-made’ environmental disasters in order to understand the role of fear and sensationalism in our relationship with the environment.” In class, I especially appreciated Roshan’s agile mind that could hold ambiguities and then present a thoughtful and articulate synthesis of those ideas. And within their essay, they also provided engaging multimodal resources in support of their claim. I invite you to enjoy their essay!

Ted Fitts

From the Writer

We are living in a time of natural disaster. As the planet warms, our relationship with nature is becoming increasingly adversarial, with rising temperatures and rising seas threatening to take away many of the things we take for granted about life on Earth. But some natural disasters seem inevitable: for example, it is very difficult to blame earthquakes and tsunamis on human actions. On March 11, 2011, Japan’s Tōhoku region experienced a trio of disasters—earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown—the likes of which no country has ever experienced. Japan has some of the most sophisticated tsunamis prediction and evacuation systems in the world, but the death toll was still catastrophic. In “Earthquake, Thunderbolt, Fire, Father,” I explore the narratives we tell ourselves about natural disasters—that sometimes, a disaster is an inescapable “act of God”—and examine what these narratives say about our relationships with our planet, our institutions, and each other.

Earthquake, Thunderbolt, Fire, Father: Community and Catastrophe in the Wake of 3/11

The cover of a police briefing following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent tsunami.

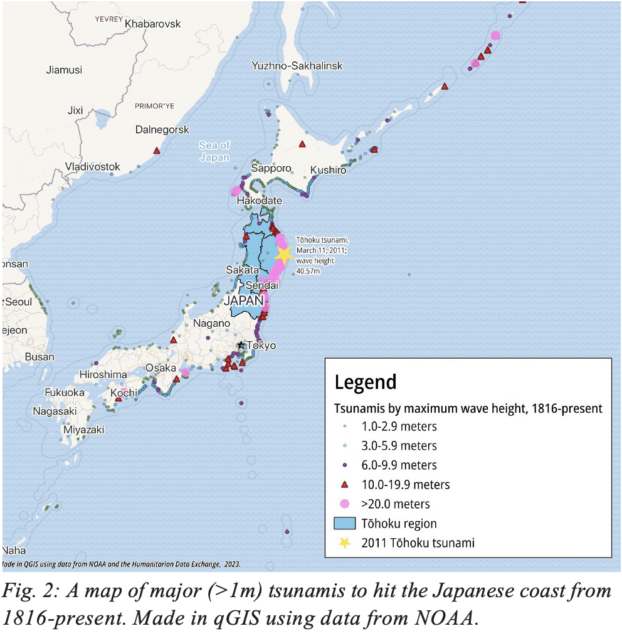

AT 2:46 PM on March 11, 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake shook the Tōhoku region of northeastern Japan, triggering a tsunami with waves up to 40 meters tall. It was the fourth tsunami to hit the region in the past two centuries (the last one being in 1960) and the most violent one in the past millennium. Though Japan had, even at the time, some of the most advanced tsunami prediction and preparedness systems in the world, the casualties were high. Nearly sixteen thousand died; almost three thousand went missing (Bestor 764). In the aftermath of the disaster, the Japanese Meteorological Agency (JMA) expanded its seismic and tsunami monitoring capabilities with a network of broadband seismometers, and the central government circulated a set of guidelines for preventive infrastructure ranging from new building codes to new breakwaters and flood gates (Koshimura 10). But the most critical detail of the new tsunami preparedness strategies was the assumption that they would fail: that buildings could fall, that flood gates could topple. Japan resurfaced from the 3.11 disasters with the lesson that nothing was foolproof in the face of nature’s might.

The American media, however, neglected to report on this lesson. The Associated Press reported, for example, on the “resilient spirit” of the Japanese people, admiring their calmness, stoicism, and seemingly unquestioning trust in their government after the crisis. “There is little of the public anger and frustra- tion that so often bursts forth in other countries,” reported Fox News journalist Kelly Olsen. To American eyes, the seemingly successful Japanese responses to the triple crises on March 11, 2011 serve as evidence that peaceful, law-abiding communities are uniquely equipped to survive natural disasters. But such an assumption is not only dangerous for the future of disenfran- chised communities in the United States–it mischaracterizes and romanticizes Japanese culture as being much more naïve than it actually is. In neglecting to report on the less convenient sides of 3.11, the American media illuminated our own aspira- tions for our relationship with nature: one of unquestioning, docile compliance in the face of crisis, and one where the only thing we have to fear is human nature, rather than nature itself. In reality, Japanese responses to 3.11 reveal a conflict between nature, community, and authority. It was local communities, not the national government, that led the most successful efforts to both escape the tsunami and to promote recovery–largely due to mistrust in the government as well as a cultural heritage based around both revering and fearing nature.

BACKGROUND

Though tsunamis are by far the most common form of natural disaster in the Japanese archipelago, they are by no means com- mon. The most recent major tsunami had been on May 23, 1960, when a 9.4 magnitude earthquake (the strongest ever recorded) off the coast of Chile sent waves up to 6 meters tall crashing into the Sanriku coast of eastern Japan (Satake 355). Since the earth- quake itself was so distant, the tsunami took Sanriku residents by surprise, prompting the Japanese government to expand its already extensive tsunami countermeasures. These ten coun- termeasures, which had been established after the 1933 Showa Great Sanriku Tsunami, included: “Relocation of dwelling hous- es to high ground, coastal dykes, tsunami control forests, sea- walls, tsunami-resistant areas, buffer zones, evacuation routes, tsunami watch, tsunami evacuation, [and] memorial events” (Koshimura 3). In 1960, the Japanese economy was thriving: the postwar government had instituted the ‘Income-Doubling Plan’ the same year, spurring rapid economic growth and conve- niently covering the costs of constructing new coastal dykes and seawalls. In 1997, the central government reinforced these countermeasures with a comprehensive three-pronged strategy: first, to protect the coastline with floodwalls, breakwaters, and coastal dykes; second, to build resilient communities with sensible ur- ban planning and land use; and third, to educate the public on how to both prepare for tsunamis and how to evacuate.

Governed separately from physical tsunami countermeasures, yet no less important, was the Japanese seismological commu- nity. Before Japan’s entry into the field, seismology was mostly a “pure science,” dominated by Westerners like Charles E. Richter (remembered for his eponymous Richter scale), who described prediction as “the province of fools and charlatans” (Clancey 334). Japanese seismology, on the other hand, was explicitly focused on predicting earthquakes: unlike Europeans, Japanese seismologists had observed firsthand the massive destruction that earthquakes and tsunamis could cause, and held a vested interest in protecting its vulnerable coastal communities from harm. Japanese scientists created the seismograph, unlocking the possibility of predicting earthquakes for the first time (Clancey 336). By the 1970s, Japanese seismologists were able to determine with a fair degree of certainty that the next major earthquake would occur in the Tōkai region; in 1978, the central government passed the Large-Scale Earthquake Countermea- sures Act, diverting significant funding towards monitoring seismic activity and establishing a council of six seismologists who would advise the prime minister on whether to issue an evacuation order–only in the Tōkai region, but still the most extensive earthquake advisory board of its kind in the world. By most accounts, Japan had the best possible strategies for surviv- ing its next great earthquake. The 2011 Tōhoku tsunami tested these strategies; some were successful, and some were not.

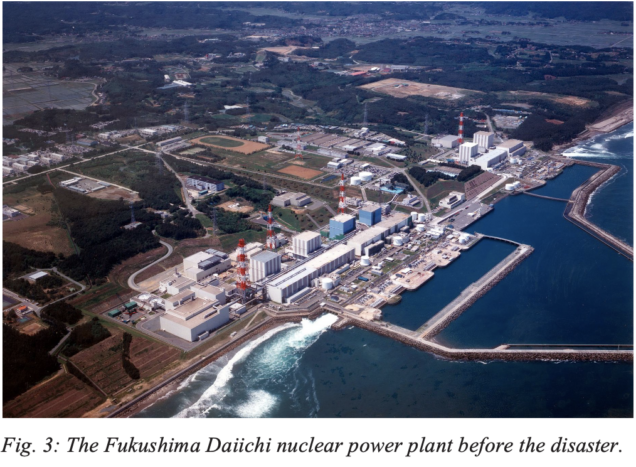

Complicating the 3.11 disaster was the reactor meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, located about 175 kilometers to the south-southwest of the earthquake’s epicenter. The earthquake tripped both the electrical generators that powered the reactor as well as the diesel-fueled backup generators, resulting in a total loss of power, disabling the reactor’s crucial cooling systems and–in turn–triggering a reactor meltdown. It is important to note that, though Japan has the most traumatic nuclear history of any country, the shadows of the 1945 bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki seem to barely affect Japan’s modern political relationship with nuclear power. Before 2011, Japan had planned to derive 30 percent of its energy from nuclear sources, and to scale that percentage to 50 percent by 2030 (Kan 16).

With six boiling water reactors (BWR) driving a series of electric generators that added up to 4.7 gigawatts in power, Fukushima Daiichi was one of the largest nuclear power plants in the world (Atomic Archive). It was also far from unprotected: at 35 feet (10 meters) above the ocean, with a 19 foot (5.79 meters) seawall, it was designed in excess of the tsunami countermea- sures proposed after the 1960 Sanriku tsunami. But the 3.11 tsunami overwhelmed these countermeasures for several reasons: first, the earthquake itself occurred just off the coast of Japan, rather than thousands of miles away; second, the tsunami itself was nowhere near the Tōkai region, where the Japanese seismological community had predicted the next tsunami to occur; and third, it moved faster than 100 miles per hour, making it impossible to evacuate in advance. Though Japan was theoretically prepared for disaster, the Tōhoku tsunami was a combination of everything it was unprepared for.

PART ONE: SOUTEIGAI

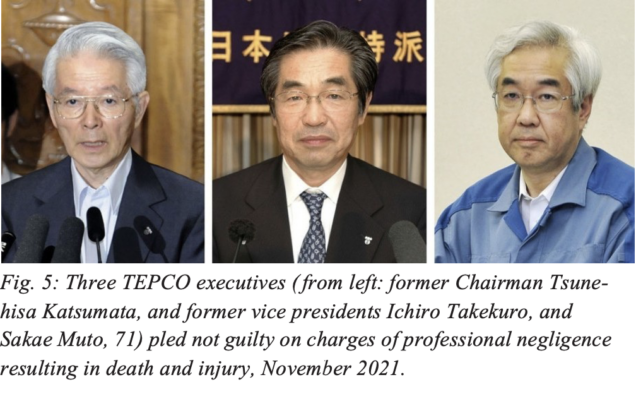

After the disaster, government spokespeople and the representatives of the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tōkyō Denryoku, or TEPCO, who operated the Fukushima plant) adopted the word souteigai to describe the events of March 11, 2011. Soutei- gai is fairly analogous to the idea of the “black swan” event, meaning catastrophic events that, while seemingly preventable in hindsight, were startling and unexpected at the time (Bestor 767). The public scoffed at this notion. Though TEPCO initially vehemently denied any culpability in the reactor meltdown, they eventually admitted to “downplaying tsunami risk, resisting adopting international safety standards, and having an institutionalized inclination to cut corners to save money in ways that jeopardized safety” (Kingston 507). Interestingly, despite vast public outcry, TEPCO’s executives were found to be not guilty of criminal negligence, though TEPCO was eventually nationalized to save the corporation from bankruptcy (Wakatsuki).

There are several problems with the “black swan” narrative–the souteigai, the act of God. In many cases, this sort of narrative positions natural disasters as “primarily accidents–unexpected, unpredictable happenings that are the price of doing business on this planet,” and they are “positioned outside the moral compass of our culture” (Steinberg xxi). It’s clear that TEPCO had intended their souteigai defense to deflect any and all accountability during the worst natural disaster in Japan’s history.

But the reactor meltdown was only a small part of the disaster: while the evacuation and quarantine of Fukushima prefecture was costly and time-consuming, the tsunami itself killed far more people. It was one thing to blame a corporation for ne- glecting safety standards; was it fair to blame the Japanese seis- mological community for failing to predict it? Or to blame Japa- nese urban planners and civil engineers for making coastal cities resilient, but not resilient enough? It seems more actionable to, like Ted Steinberg, argue that there is really no such thing as a “natural” disaster, and that the responsibility falls entirely on human hands. But such an argument is ripe for creating civil unrest and social strife. Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) identifies two types of crises: first, the intentional or preventable crisis, in which a human actor causes the crisis; and second, the victim crisis, in which natural forces cause the crisis. Social scientists at VU University Amsterdam conducted a framing experiment using the Fukushima crisis as a target. In the “intentional” crisis framing, respondents were more likely to react angrily, with 66% of 71 respondents holding TEPCO responsible for the incident. They were also more likely to be “motivated to do something about the incident because they believe that they can influence the situation” (Utz 42). In the “victim” crisis, on the other hand, 72% of 54 of respondents blamed the incident on circumstances (Utz 44). These respondents were also more likely to react with a sense of helplessness, an emotion that was felt across the Tōhoku region–and especially those who were not directly impacted by the radioactive fallout from Fukushima.

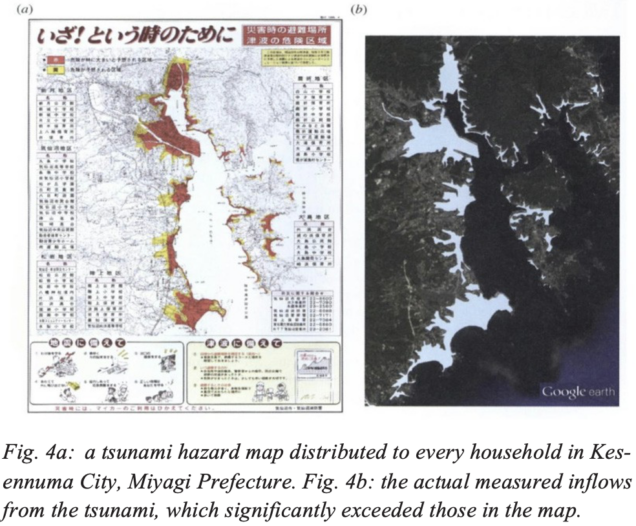

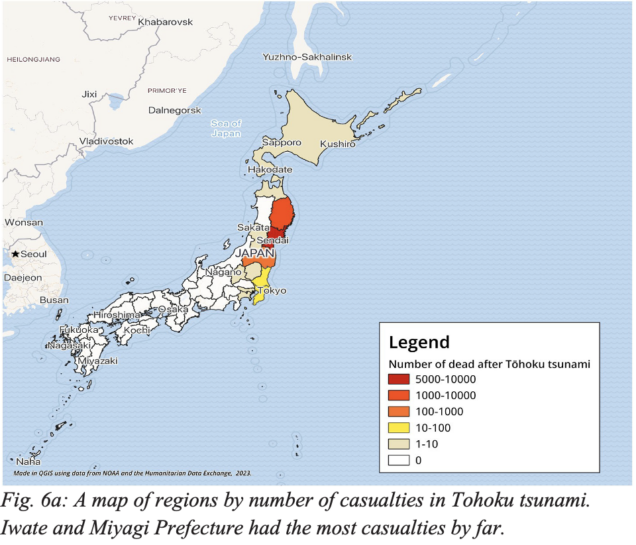

What does one do, when regional corporations cannot be trusted to safeguard hazardous materials, and even the best seismic experts in the world cannot be relied upon to predict the next town-destroying tsunami? If it were just the corpora- tions, it would be easy enough to seek legal action. But for much of Japan, the effects of 3.11 rippled out into a lack of trust in the government and in authority in general. This was in large part because many of the groups that survived the tsunami did so by ignoring the government-circulated hazard maps, assuming that the tsunami would travel much higher along the coastline than the government predicted. Similarly, Kamaishi East Junior High School had one of the highest survival rates of any school in the area because they had been taught three lessons of evacuation by Gumma University professor Toshitaka Katada: to “not trust hazard maps, to make their best efforts in any situation, and to take the initiative of evacuation in the community” (Koshimura 10). But this lack of trust in authority, though it had saved thou- sands of lives during the tsunami, only exacerbated an already widespread feeling of helplessness and social anguish. After the disasters, the then-incumbent Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was ousted in a landslide victory by the Liberal Democratic Party and an assortment of small, idealistic local parties, such as the Tomorrow Party of Japan. It is especially notable that the regions with the most unexpected political turnover (such as the rural, conservative Miyagi and Iwate prefectures) were also those that were hit hardest by the disasters (see Figs. 6a and 6b).

PART TWO: KIZUNA

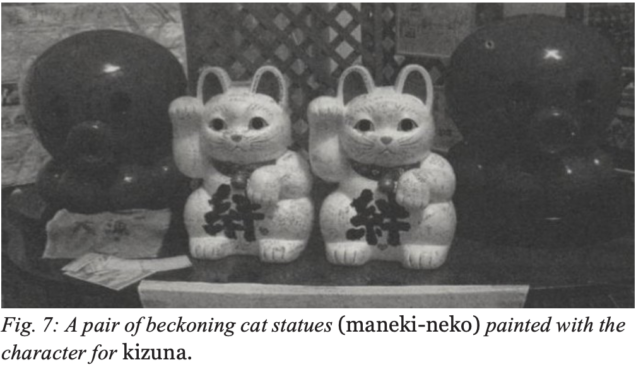

The antidote to social anguish is community. In a trust experiment that was coincidentally interrupted by 3.11, social scien- tists attempted to gauge to what extent Japanese citizens trusted their peers after the ment that was coincidentally interrupted by 3.11, social scientists attempted to gauge to what extent Japanese citizens trusted their peers after the disasters. In the experiment, participants consistently and significantly underestimated the trustworthiness of their peers, expecting 40% to return a certain small sum of money when 80% did so (before 3.11). The number of participants to return the money also increased after the earthquake, from 80% to 100% (Veszteg 126). Thus, though people generally distrusted authority, they could usually trust in their own communities; people were more likely to trust someone who had placed trust in them, and communities could weather recovery through mutual trust rather than through trusting authority. This is an example of the Japanese idea of kizuna, meaning “human psychological ties,” which went on to become Japan’s 2011 Kanji of the Year.

Both American and Japanese media have reported extensively on kizuna, mostly to admire the Japanese people’s stoicism and order following the disasters. American perceptions of Japanese culture generally fall under the assumption that the Japanese follow a “group model” of society, one based on the paternalism of authority figures, selfless loyalty to the prosperity of the group, and on conformity and cooperation rather than competition and conflict (Befu 170). While this idea of kizuna seems to reflect the values of the group model–especially that of mutual prosperity–it is especially characterized by a lack of trust in authority. Kizuna and the post-3.11 era are not reflections of “Japanese cultural DNA,” as much of the Western media argued. They are instead signs of communities coming together in the face of crisis, rejecting scientific and governmental authority in favor of community wisdom.

It is through community that the Japanese people find their relationship with nature and authority alike, and that relationship is one based mostly on fear. Japanese proverbial wisdom outlines four fears that present danger to the bonds of community: these fears are jishin, kaminari, kaji, oyaji, or earthquake, thunderbolt, fire, father. Three are natural and literal; the fourth, “father,” represents paternal rage (or government tyranny).

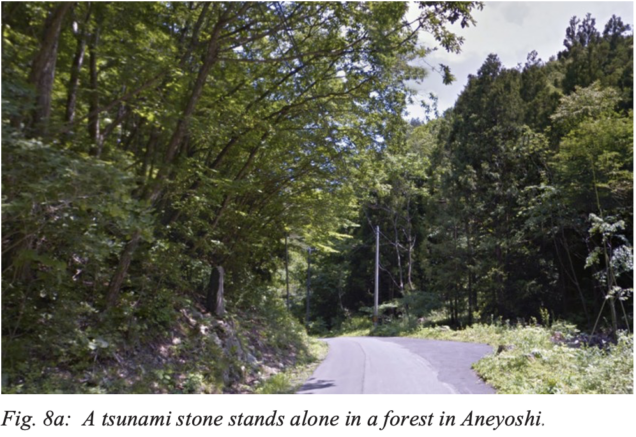

Jishin, kaminari, kaji, oyaji suggests that danger is everywhere, technology is untrustworthy, and the first thing to fear is earth- quakes. Thousands of tsunami stones (see Figs. 8a and 8b)–built hundreds of years ago in villages across the Japanese archipelago-warn residents not to build below certain elevations, in a piece of antique wisdom that saved numerous villages on 3.11. They are simple, yet effective: “Many carry simple warnings to drop everything and seek higher ground after a strong earthquake. Others provide grim reminders of the waves’ destructive force by listing past death tolls or marking mass graves” (Fackler). Also indicative of the Japanese fear of earthquakes is, again, that seismology was Japan’s first science. Just as many of the first American inventions were used for agriculture, the fear of earthquakes is ingrained deep into the Japanese subconscious.

In reporting about the 3.11 disasters, American media outlets admired a few characteristics of the Japanese survivors. The As- sociated Press reported on the Japanese’s “resilient spirit,” noting the “polite demeanor, the lack of anger, the little if any looting or profiteering that seems to characterize disasters elsewhere” (Alabaster). This focus on looting and profiteering is characteristic of American coverage on natural disasters–during Hurricane Ida, for example, the New Orleans Police Department instituted “anti-looting” teams, disproportionately in Black communities. The reality was that many of the stories of looting were entirely fabricated. One activist in New Orleans told TIME Magazine,

“I have not seen any looting, any smashing, any aggression. I’ve seen people helping each other. I’ve seen people showing up for each other. I have not seen any [helpful] actions from the police” (Bates). At the same time, diverting police resources towards “anti-looting” prevented those same resources from providing shelter and aid to families in need. The Japanese’s supposedly “uncomplaining” response to the 3.11 disasters seems like an American policymaker’s dream, but that view obscures the very real distrust and uncertainty that was brewing at the same time. American media outlets also tended to ignore regions of Japan that were swept away by the tsunami in favor of covering the radioactive fallout from Fukushima. It is very American to ignore the natural side of a natural disaster; it is a black swan, an act of God, and therefore is irrelevant because there is no one to answer for it. In the American view, the real tragedies are man-made, from negligence at a nuclear power plant to looting during a hurricane, regardless of whether or not they even exist. After 3.11, the lesson the Japanese learned could not be any further from what the American media learned: authority, even scientific authority, is untrustworthy, and the only thing that can save people from the ravages of nature is not authority–it is community.

Community–kizuna–is one of the biggest threats to authority, and has the potential to completely overturn the American natural disaster response. A similar trust experiment to the one conducted in March 2011 had been conducted after Hurricane Katrina, and discovered that the respondents also significantly underestimated the trustworthiness of their peers, and especially their peers of other racial and socioeconomic backgrounds (Hawkins 1784). This is the limitation of using Japan as a model for natural disaster response: Japan is, unlike the United States, relatively racially homogenous. Its homogeneity is also a product of decades of nationalistic policies and ethnic supremacy; it is significantly easier to place trust in one’s community when they look like you and act like you. Ironically, the Japanese model for a relationship with nature is fairly libertarian: the government has little say in how people interact with nature, just as people have little say in how nature affects them. Japan’s response to 3.11 is a lesson in community-building and in fear: it is safer to fear nature than to fear nothing at all.

WORKS CITED

“Aichi Rescue Officer Remembers Information Black- out after 3/11.” The Japan Times, Chunichi Shimbun, 26 Feb. 2021, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/02/26/ national/311-information-blackout/

Bates, Josiah. “New Orleans Wary as Police Aim at Looting amid Hurricane Ida.” Time, Time, 2 Sept. 2021, https://time. com/6094022/new-orleans-hurricane-ida-looting/.

Befu, Harumi. “The Group Model of Japanese Society and an Alternative.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, 1980, p. 169-187.

Bestor, Theodore C. “Disasters, Natural and Unnatural: Reflections on March 11, 2011, and Its Aftermath.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 72, no. 4, 2013, pp. 763–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43553226. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

Clancey, Gregory. “Japanese Seismicity and the Limits of Prediction.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 71, no. 2, 2012, pp. 333–44. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23263423. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

“Ex-TEPCO Execs Plead Not Guilty over Fukushima Crisis in Appeal Trial.” Kyodo News+, KYODO NEWS, 2 Nov. 2021, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2021/11/3cd65ba68a5d-ex- tepco-execs-plead-not-guilty-over-fukushima-crisis-in-appeal- trial.html.

Fackler, Martin. “Tsunami Warnings, Written in Stone.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 20 Apr. 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/world/asia/21stones.html?pagewanted=al.

“Fukushima.” Atomic Archive, https://www.atomicarchive.com/science/power/fukushima.html.

Hawkins, Robert and Katherine Mauer. “Bonding, Bridging and Linking: How Social Capital Operated in New Orleans Follow- ing Hurricane Katrina.” British Journal of Social Work. 2010. pp. 1777-1793. 10.1093/bjsw/bcp087.

Hunchuck, Elise. “2015 – 2017: An Incomplete Atlas of Stones.” elisehunchuck, https://elisehunchuck.com/2015-2017-An-Incomplete-Atlas-of-Stones.

Kan, Naoto. “The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Disaster and the Future of Renewable Energy.” My Nuclear Nightmare: Lead- ing Japan Through the Fukushima Disaster to a Nuclear-Free Future, Cornell University Press, 2018, pp. 3–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt20d89f7.2. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

Olsen, Kelly. “Quake Response Showcases Japan’s Resilient Spirit.” Fox News, The Associated Press, 27 Mar. 2015, https://www.foxnews.com/world/quake-response-showcases-japans-resilient-spirit.

Stokes, Bruce. “Japanese Divided on Democracy’s Success at Home, but Value Voice of the People.” Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, Pew Research Center, 31 May 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2017/10/17/japanese-divided-on-democracys-success-at-home-but-value-voice-of-the-people/.

Utz, Sonja, et al. “Crisis Communication Online: How Medium, Crisis Type and Emotions Affected Public Reactions in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster.” Public Relations Review, vol. 39, no. 1, Mar. 2013, pp. 40–46., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.010

Veszteg, Róbert Ferenc, et al. “The Impact of the Tohoku Earth- quake and Tsunami on Social Capital in Japan: Trust before and after the Disaster.” International Political Science Review / Re- vue Internationale de Science Politique, vol. 36, no. 2, 2015, pp. 119–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24573456. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

LIST OF FIGURES

1 (cover). “東日本大震災に伴う警察措置|警察庁Webサ / Po- lice Measures Associated with the Great East Japan Earthquake.”警察庁 / National Police Agency of Japan, https://www.npa.go.jp/news/other/earthquake2011/keisatsusoti.html.

2. Made in QGIS using data from “Tsunami Data and Infor- mation.” Tsunami Data and Information | National Geophysi- cal Data Center. NCEI, U.S. Department of Commerce, 28 July 2006, https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/hazard/tsu.shtml.

3. “Fukushima.” Atomic Archive, https://www.atomicarchive.com/science/power/fukushima.html.

4a, 4b. Koshimura, Shunichi, and Nobuo Shuto. “Response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster.” Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and En- gineering Sciences, vol. 373, no. 2053, 2015, pp. 1–15. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24506317. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

5. “Ex-TEPCO Execs Plead Not Guilty over Fukushima Crisis in Appeal Trial.” Kyodo News+, KYODO NEWS, 2 Nov. 2021, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2021/11/3cd65ba68a5d-ex-tepco-execs-plead-not-guilty-over-fukushima-crisis-in-appeal-trial.html.

6a. Made in QGIS using data from “東日本大震災に伴う警 察措置|警察庁Webサ / Police Measures Associated with the Great East Japan Earthquake.” 警察庁 / National Police Agency of Japan, https://www.npa.go.jp/news/other/earthquake2011/keisatsusoti.html.

6b. Made in QGIS using data from “Results for the December 2012 General Election.” Nippon, Nippon News, 30 May 2020, https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00020/.

7. Bestor, Theodore C. “Disasters, Natural and Unnatural: Re- flections on March 11, 2011, and Its Aftermath.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 72, no. 4, 2013, pp. 763–82. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43553226. Accessed 11 Mar. 2023.

8a. Hunchuck, Elise. “2015 – 2017: An Incomplete At- las of Stones.” Elisehunchuck, https://elisehunchuck.com/2015-2017-An-Incomplete-Atlas-of-Stones.

8b. Fackler, Martin. “Tsunami Warnings, Written in Stone.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 20 Apr. 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/world/asia/21stones.html?pagewanted=al.

Roshan Sivaraman is a sophomore pursuing a Dual Degree in International Relations (BA) and Voice Performance (BM) at Boston University. While their diploma will say “international relations,” Roshan prefers to say that they are particularly interested in human-environment relations, especially in those of Asian cultures. As such, they are currently studying in Singapore, while also working on peatland restoration in Indonesia’s Riau Archipelago. Roshan credits this paper, and the wonderful, warm, and encouraging teachings of their WR120 professor, Professor Ted Fitts, for sparking what will be a lifelong interest in how people interact with nature.