Men’s Migration and Women’s Lives: Evidence from Nepal

By Pratistha Joshi Rajkarnikar

With over 272 million individuals living outside their countries of birth, migration has become one of the most salient features of our times. Much of the literature on migration focuses on the economic benefits of remittances sent home by these migrants. As of 2018, remittances amounted to USD 689 billion and was the largest source of foreign capital for developing countries.

Figure 1. Total number of migrants in the world, Select years

Source: World Migration Report, 2020

The impacts of migration go far beyond just economic gains. Migrants significantly transform the socio-cultural and political structures of both origin and receiving countries, through transfers of social, political, and human capital.

One key consequence of migration is the emergence of transnational households, where families are divided across borders, but continue to share common resources and make decisions jointly. This creates new social structures, which are especially striking in societies with strictly defined gender roles, where men migrate to provide for the family, while women stay behind to provide care.

This transformation in gender roles is one of the central features of labor migration from Nepal, where over half of the country’s households have at least one migrant member and remittances account for more than a more than a quarter of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

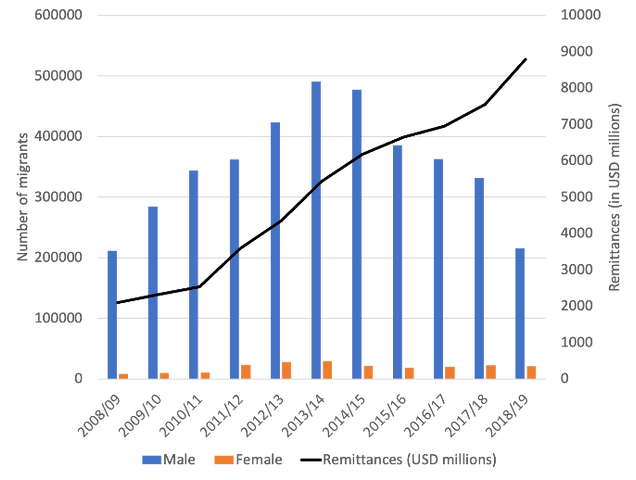

Indeed, in the decade ending in 2018, over 4 million Nepalese workers received government permits to pursue foreign employment and more than 90 percent of these migrants were men.

Figure 2. Total number of migrants by gender and total remittances received (in millions of US dollars), Nepal

Source: Migration in Nepal, A Country Profile, 2019.

This male-dominated migration has considerably transformed intra-household power relations and resulted in large changes in women’s roles and responsibilities in the domestic and socioeconomic spheres. Women are increasingly taking up the role of household heads, financial managers, and single parents, in a society that has historically suppressed their freedom. Despite these newfound opportunities, the continued existence of gender-segregated labor markets, and inequities in health, education, and restrictions on physical mobility, present significant challenges for women to cope in their new roles.

In-depth research on the gendered impacts of male migration from Nepal reveals a complex picture where women gain opportunities for increased freedom and greater access to economic and social resources during men’s absence, but these opportunities are often constrained by women’s position in the household, their education and employment background, and gendered social norms. The study used a mixed method research, based on quantitative analysis using data from Nepal Living Standard Survey-III (2010/11) and the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011 and qualitative analysis based on fieldwork interviewing 178 women in four districts of Nepal.

Main Findings: Women’s Work Responsibilities, Market Participation and Household Work

One of the direct consequences of migration of men is a change in the gender division of labor. Women’s participation in market work is likely to increase if they gain more freedom in the absence of men, or if barriers to entering the labor market for women start disappearing due to shortage of labor. In the case of Nepal, it is, however, seen that women in migrant households have higher domestic and subsistence farming responsibilities and lower participation in market work.

This lower participation in market work for migrant wives is partly explained by the intensification of their domestic work, along with the reduced economic pressures by virtue of receiving remittances. Because of this increase in unpaid work, migrant wives are more likely to remain financially dependent on their husbands. Though they perform vital economic and social functions of household maintenance, their ability to contribute to the family’s economic security declines, thus reinforcing men’s role as the primary breadwinners and maintaining women’s subordinate position in the household.

Agency and Decision-Making

Migration of men is likely to increase women’s autonomy and decision-making power within the household. However, women’s ability to participate in household decision-making may be constrained by their financial dependence on men, as well as social norms on what is expected of them.

Analysis on changes in women’s decision-making power during men’s migration, in the case of Nepal, suggests that the outcome is mainly dependent on women’s position within the household. Women who take on the role of household heads are more likely to gain decision-making power, while those left under the supervision of other members (usually their in-laws) may suffer from reduced decision-making ability.

However, even when women gained decision-making power, the most important decisions – especially those related to financial matters – were made by men. In fact, women often worried about not being able to manage money by themselves and preferred consulting with their husbands, partly because of their economic dependence on men. In extended households, where women experienced either a decline, or no change in their decision-making role, the in-laws were the primary decision-makers.

Most migrant wives also faced higher social scrutiny and increased vulnerabilities during their husbands’ absence, limiting their participation in social spaces. Women who took on the role of household heads in their husband’s absence often had to step into public spaces out of necessity to maintain their livelihood (going to the market, health center or bank). While these women experienced an increase in their social participation, they often complained about increased stress from having to break social barriers and step into public spaces.

The only aspect of increased social participation that women seemed to appreciate was the stronger bond they formed with other women in the society, as they depended on each other for support.

For women in non-head positions, the need to step into public spaces was less severe as they lived in extended households, where other male members could take up work requiring public interaction. These women, in most cases, experienced greater restrictions on their physical mobility in the absence of their husbands.

Regional Differences

The different socio-economic conditions in the four research locations selected for the fieldwork also illustrated important differences in women’s experiences. Two districts (Chitwan and Siraha) were selected from the Terai region of the country, where gender norms are much more restrictive than the other two districts (Rolpa and Syangja) selected from the Hill region. Women’s participation in household decision-making and in public spaces was much higher in the Hill districts, than in the Terai.

Participation in market work was higher for women in the districts with higher poverty rates (Siraha and Rolpa). However, the type of employment for women in these two districts were very different. Women in Siraha were more likely to be involved in home-based production and low-skilled jobs, while women in Rolpa had higher educational qualifications and were often employed in the skilled-labor sector in government offices and as schoolteachers – a difference possibly attributable to the less restrictive gender norms in the Hills.

Policy Implications

The study’s findings help understand the consequences of migration from a gendered perspective and provide insights that may be valuable in developing a socio-political framework for fighting gender inequality and providing women with necessary resources and relevant skills to undertake new roles.

Most issues associated with difficulties faced by women during men’s absence are rooted in gender-based social and structural barriers in Nepal. Reducing these difficulties requires breaking oppressive relations by raising awareness through community programs, or media outlets and increasing access to education and employment opportunities for women.

Provision of public services for child and elderly care, state support towards accessing resources that facilitate performance of unpaid household work – such as access to fuel and water – along with policies to encourage access to labor market and ensure fair wages might help reduce some of the stress of domestic work and allow women to exercise greater autonomy in taking up paid work. Such policies might also help reduce their dependence on male migrant members, strengthen their agency, and contribute towards their empowerment.

As global migration rates continue to rise, it is increasingly important to consider such gendered consequences to ensure the well-being of families left behind.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter.