Putting Women’s Work in Context: What Mainstream Economics Misses About Gender

By Stacey Yuen

The tendency of mainstream economics to focus almost exclusively on market activities suggests a fundamental problem with the discipline: it is gender biased. It fails to recognize and value many forms of work that are mostly done by women and are essential to the functioning of our societies, such as caring for family members and maintaining households.

Lessons on Gender from the COVID-19 Pandemic

This problem comes to the fore when analyzing the gendered consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. In February 2021, the World Bank observed that the economic crisis arising from the pandemic is impacting men and women differently. As a disproportionate number of women work in healthcare and engage in unpaid care and domestic work, they are more susceptible to the detrimental consequences of the pandemic. Women, more than men, bear the double burden of working longer shifts at care institutions, while also taking on additional care responsibilities at home.

Such news, although adverse, is not surprising. In recent decades, the gendered division of labor – the allocation of different types of jobs to men and women – has attracted scrutiny from a growing number of scholars. Attention is also being paid to the impact of such labor division on the economy and workers’ well-being, and to the resulting policy implications.

What the pandemic draws into focus, however, is the magnitude of the costs incurred by that division, made apparent by the yawning gap between the social value of such care work and the price that the market puts on it. In 2015, for example, unpaid family caregiving in the US was worth an estimated $470 billion, or 2.57 percent of GDP. For the same year, the average value of unpaid labor for 27 mostly high-income countries was estimated to be more than 25 percent of GDP.

Although care workers and other frontline essential workers are indispensable to the well-being of patients and their families, and to the broader economic and social institutions, a disproportionately large number of such workers earn low wages. In 2016, the median hourly wage for home care workers in the US was $10.49. In 2017, the average salary for registered nurses in the US was $67,300, but the average salary for nursing, psychiatric, and home health assistants was $29,700. The gap further widens when accounting for the physical risks and strains borne by care workers during the pandemic.

The problem, in other words, is twofold: the market fails to fairly valuate and compensate for care work, and some workers (such as women) suffer from that under-valuation of their labor more than others. Yet, neoclassical economics – as taught in the mainstream curriculum – falls short in explaining and tackling such issues of inequities.

What Neoclassical Economics Misses About Gender and Households

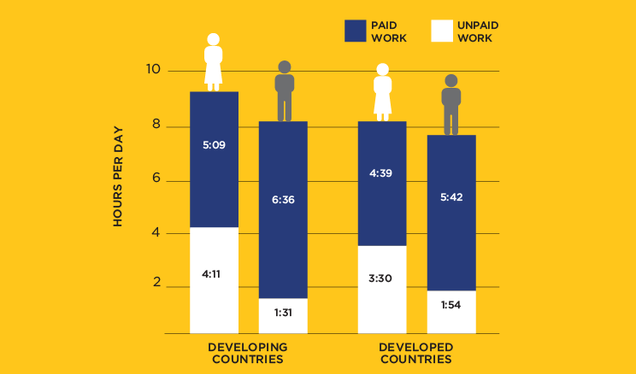

Neoclassical economics effectively substitutes markets for the economy by focusing almost exclusively on market activities. Because the economic value of all things is measured in monetary terms, services or items that cannot be accurately priced are often excluded from economic analysis. That includes care and domestic work, which is often undertaken by women. According to the United Nations, women carry out at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men globally (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time Spent on Paid and Unpaid Work for Employed Persons by Sex, 2016

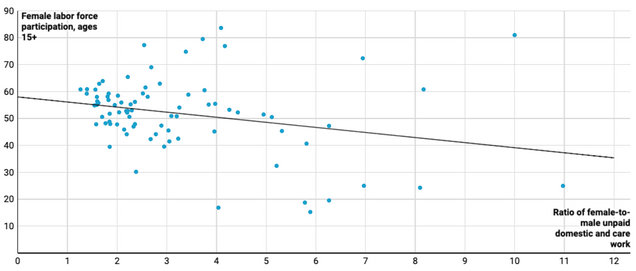

Furthermore, women’s continued engagement in unpaid and underpaid work challenges neoclassical assumptions about rational self-interest; that is, that decision-making processes are driven by optimization. Across countries, gender inequalities in unpaid domestic and care work are associated with lower rates of female labor force participation (Figure 2). Why might an individual engage in unpaid care work if it effectively substitutes for paid market work? Evidently, sources other than rational self-interest are at play. Actual decision-making is often shaped by communal interests, social norms, and concern for others – all of which could explain individuals’ decision to engage in care work, but that are neglected in neoclassical analysis.

It should be observed that such kinds of “sub-optimal” care work form the bedrock of markets and human well-being. They sustain families, support economies and often cover for the lack of social services, yet are seldom recognized or valued as work. Put another way, households and communities form a primary site for major economic activity, in which the primary economic agents are most often women. The market-exclusive focus of a traditional economics curriculum is simply unable to account for the full range of economic activity that human beings engage in.

Figure 2. Unpaid Work and Female Labor Force Participation

Mainstream economics also largely ignores intra-household inequities. By taking the household as the unit of analysis, it assumes that the (male) household head always acts to maximize the well-being of all household members. This is not always true. Even though household members are tied by love and affection, they also experience conflicts because of the need to share limited resources. Women’s engagement in unpaid care work, their limited participation in household decision making, and their lack of access to various economic and social resources, exposes the limitations of neoclassical theory in explaining gender inequalities within the household and society at large.

Putting Economics in Context

A curriculum that seeks to educate students in real-world economics therefore cannot afford to limit economics analysis to only the market sphere, or to rely on the “rational man” as a key model for decision-making. It should be noted that neoclassical economics is not value-neutral: it takes growth in consumption, achieved by increasing productive efficiency, as its final goal. That value system competes with other ideals such as fairness and justice, well-being across present and future groups, co-operation, and mutual aid. In that regard, the mainstream economic curriculum needs reform.

A nuanced approach to economics education is all the more necessary given the complex and evolving challenges that modern societies face, including persistent and rising income disparities, the different ways that gender, race, and other demographic factors interact to produce inequities, and the growing climate threat. As subject curricula increasingly trend towards interdisciplinary approaches, economics, too, should resist silos. A forward-thinking economics curriculum will equip students to consider questions of well-being, ethics, equity, and sustainability alongside economic analysis. Already, the global student climate strikes that began in 2018 suggest that students are eager to engage the social, environmental, and economic considerations of their time.

In view of those needs, the Economics in Context Initiative (ECI) has developed a series of introductory economics textbooks and modules, which analyze economics within its broader social and environmental contexts. This approach, termed “contextual economics,” takes as its ultimate goal the well-being of all people, present and future, in all of their economic and social roles. It identifies the “core sphere,” which includes households and communities, that take on most of the unpaid work, as a key economic sector and explores the integration of such work into national accounting measures.

In doing so, the ECI attempts to bridge the divide between the economics taught in schools and real-world economics, thus making economics work better for real people.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter.