It Looks Loopy, But It Works

Loops of string make rock piles stand tall in study by Holmes and Guerra

By Patrick L. Kennedy

Say a missile or an earthquake has just damaged your apartment building. Stone rubble litters the street. Must you wait for the Army Corps of Engineers to arrive, clear away the rubble, and rebuild the blasted wall? Or, like MacGyver, could you make use of that rubble, and some twine, to erect a temporary wall?

That’s the scenario that the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency had in mind, and they wanted Associate Professor Douglas Holmes (ME, MSE) to work it out. In his latest publication in an ongoing line of research, Holmes, along with doctoral student Arman Guerra, determined that it is possible to build free-standing, load-bearing structures using only rocks and loops of string—if the rocks are rough enough, the string is stiff enough, and the loops are spaced just right.

Holmes and Guerra’s new study, in Soft Matter, is called “Emergence of structure in columns of grains and elastic loops.” When Holmes and Guerra say “elastic loops,” they don’t mean rubber bands, but rather rope, or any slender, ribbon-like fibers. And by “grains,” they mean not wheat but rocks—or maybe peanut M&Ms, or any assemblage of spheroids that together can act as a fluid.

You might not expect a bunch of rocks to behave like a fluid. But picture a landslide. Those rocks will certainly flow downhill. Unlike water, though, rocks will form a little hill themselves if you dump them in one place—and if the rocks are sufficiently ridged. In other words, depending on the rocks’ frictional properties. The tiny bumps on their surfaces make the rocks naturally stick together, up to a point.

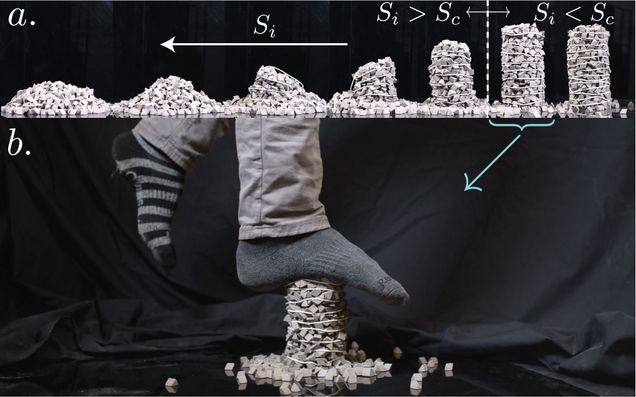

What Holmes and Guerra have done is figure out a formula for turning that loose pile into a practical, temporary column that can withstand an impressive amount of compressive force. Their method is to loop string around the pile (which they build up layer by layer) in such a way that the string “jams” the rocks, essentially turning them into one big rock.

“An example of jamming is a vacuum-packed container of coffee beans,” says Holmes. “It’s like a brick. Jamming is what happens when you restrict a bunch of grains that flow like a liquid, so that they behave like a solid.” The loops of string restrict the rocks by adding points of contact, preventing the rocks from moving.

Surprisingly, the loops can be spaced quite far apart, if the grains have enough friction to them. “That critical spacing can actually be a bit bigger than the size of the rocks,” says Holmes. “Because there’s friction helping to keep them in place, along with the loops. Our formula is based on how flexible the string is and what the frictional properties of the grains are.”

In addition to making columns, Holmes and Guerra have collaborated with MIT architecture professor Skylar Tibbits on grain-and-loop structures that can be turned into beams or plates, and they continue to investigate ways to do that.

“It’s so cool,” says Guerra. “When you’re standing on one of these things, you feel like, ‘This shouldn’t be able to work!’”

Eventually, Holmes would like to see this minimalist technology applied to more ambitious temporary structures, shoring up roads or sea walls in ways that don’t butt heads with nature.

“We could think about not using ropes at all,” Holmes says. “Maybe we should use the roots of growing materials to stabilize structures to prevent erosion, from wind or water. To have some natural component that could help them be self-healing and adaptable to changes in the land. There are a ton of ways we could make these temporary structures permanent, but I think that harmonious approach is more compelling.”