The Ways Boston Helped Shape the Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59)

The civil rights leader lived, studied, met his wife here, returned to give powerful speeches

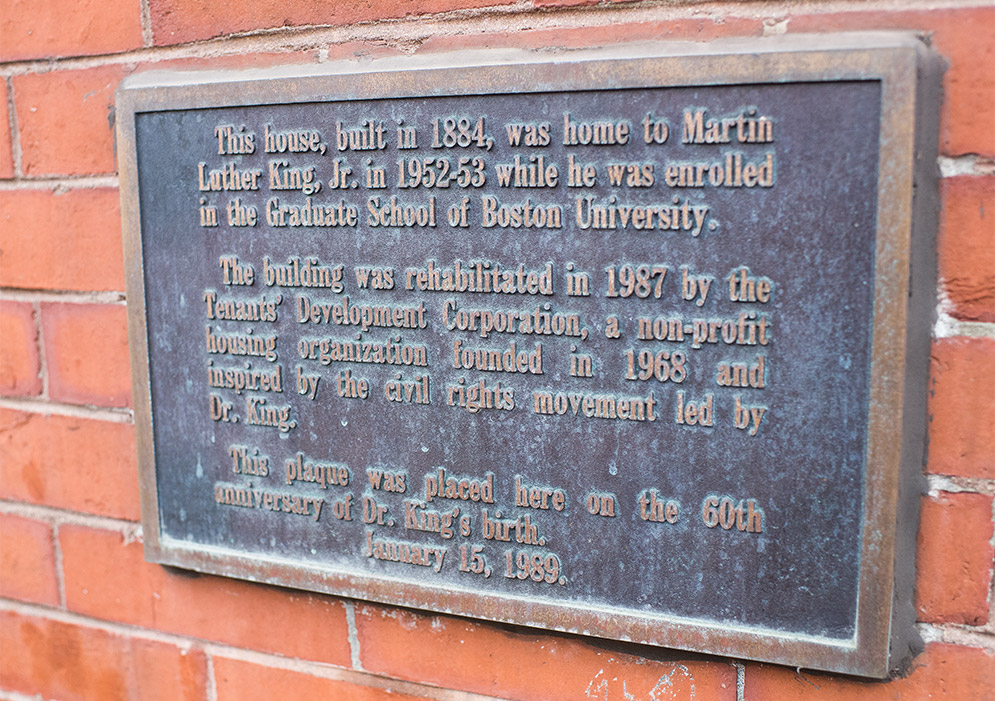

A plaque on the outside of 397 Massachusetts Avenue in Boston, where Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) lived in 1952 and 1953. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi.

A plaque on the outside of 397 Massachusetts Avenue in Boston, where Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) lived in 1952 and 1953. Photo by Jackie Ricciardi.

It might seem curious at first that Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) is getting a memorial on Boston Common. He wasn’t born in Boston. He didn’t die here. He didn’t give a famous speech here. But Boston, in fact, may have influenced the life of the civil rights icon both personally and professionally as much as any city in America.

He lived here for three years, worked here, studied at, and graduated from, Boston University, and it was here he and met and dated the woman he would go on to marry. It was also in Boston where he revisited his most famous speech, “I Have a Dream.” So yes, it makes sense why the Common will soon be home to a prominent memorial to MLK.

Where did he live?

During his time in Boston, King had several known addresses. One was 395-397 Massachusetts Avenue, a three-story brownstone in the South End where a plaque is attached to the red brick: “This home, built in 1884, was home to Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1952-53 while he was enrolled in the Graduate School of Boston University.” He also called 396 Northampton Street in the South End, just behind the Mass Ave MBTA station, home. He listed that apartment in a letter in 1954, which means that presumably it was the first place he lived with Coretta Scott after their 1953 marriage. He also spent a short time at 170 Saint Botolph Street, another South End brownstone.

When he needed a break from his graduate studies, King often wandered over to the William E. Carter Playground in the South End to play pickup basketball.

Where did he study?

Martin Luther King, Jr., received an honorary degree from Boston University at the 1959 Commencement on June 7. Photo by BU Photography.

After studying at Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pa., King arrived in Boston in 1951 to study at BU, with a special interest in philosophy and ethics. It was the PhD in systematic theology he earned at BU that gave him the right to be called Dr. King for the remainder of his life. According to his transcript at BU, he also took courses at Harvard, including the Philosophy of Plato.

BU’s School of Theology says this about his studies: “During these years, Howard Thurman was named dean of the University’s Marsh Chapel. King not only attended sermons there but also turned to Thurman as his mentor and spiritual advisor. Among the lessons that inspired him most were Thurman’s accounts of a visit to Mohandas Gandhi in India years earlier. It was Thurman who educated King in the mahatma’s ideas of nonviolent protest. As the bridge between Gandhi and King, BU’s progressive dean helped sow the seeds of change in the US and beyond.” Thurman (Hon.’67) was Marsh Chapel dean from 1953 to 1965, the first black dean at a mostly white American university.

Approximately six months after graduating from BU, King led the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., where he first began to attract national recognition. He returned to Boston in 1964—the same year he received the Nobel Peace Prize—to donate his personal papers to BU; the collection is among the most prominent held by the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

One final note on his BU years: King did not attend his BU graduation in 1955. He wrote the University that his wife was pregnant and financial hardships made it impossible for him to return for Commencement, so BU mailed his diploma. He did come to Boston to receive an honorary degree from BU in 1959.

Where did he meet his future wife?

Photo courtesy of Rev. David Briddell (STH’58).

Biographers have made no secret of King being something of a ladies’ man when he arrived in Boston. But it was a friend’s suggestion that he meet a young woman studying opera at the nearby New England Conservatory of Music, who was also earning money doing housework, that changed his life.

In his autobiography, he described how he met Coretta Scott:

“We met over the telephone: ‘This is M. L. King, Jr. A mutual friend of ours told me about you and gave me your telephone number. She said some very wonderful things about you, and I’d like very much to meet you and talk to you.’

“We talked awhile. ‘You know every Napoleon has his Waterloo. I’m like Napoleon. I’m at my Waterloo, and I’m on my knees. I’d like to meet you and talk some more. Perhaps we could have lunch tomorrow or something like that.’

“She agreed to see me. ‘I’ll come over and pick you up. I have a green Chevy that usually takes ten minutes to make the trip from B.U., but tomorrow I’ll do it in seven.’

“She talked about things other than music. I never will forget, the first discussion we had was about the question of racial and economic injustice and the question of peace.”

Their first date was at a chain restaurant called Sharaf’s on Mass Avenue.

Did he return to Boston on other occasions?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (at podium) is applauded after a speech to the joint session of the Massachusetts Legislature in Boston April 22, 1965, the day before he led a civil rights march to Boston Common. (AP Photo, File).

King would leave the city in 1954, as he wound down work on his PhD, but returned to deliver a forceful speech at the Massachusetts State House just months after he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

On April 22, 1965, he appeared before a joint legislative session at the Massachusetts State House. He closed his remarks by quoting his “I Have a Dream” speech, which he had famously made in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963.

The day after his Boston speech, King led a freedom march of more than 20,000 people from the South End to Boston Common, where the planned memorial will be constructed. “Now is the time,” he told the crowd, “to make real the promise of democracy. Now is the time to make brotherhood a reality. Now is the time.”

Author, Doug Most can be reached at dmost@bu.edu.